Who Was Charles Fletcher Lummis?

Artbound revisits early Los Angeles to explore one of its key and most controversial figures: Charles Fletcher Lummis. As a writer and editor of the L.A. Times, an avid collector and preservationist, an Indian rights activist, and founder of L.A.’s first museum, Lummis’ brilliant and idiosyncratic personality captured the ethos of an era and a region. Watch Artbound's season eight debut episode, "Charles Lummis: Reimagining the American West," premiering Tuesday, May 10 at 9 p.m., or check for rebroadcasts here.

Pity Charles Fletcher Lummis. Because he was larger than life, Lummis painted himself a corner into which he has been placed by posterity. Because he was a hedonist character, who bucked convention with his roaring ego, his life was outlined by caricature. In that corner inhabited by “Lum” or “Charlie,” his legacy is often marked by too-easily reached assessments of the man and his significance.

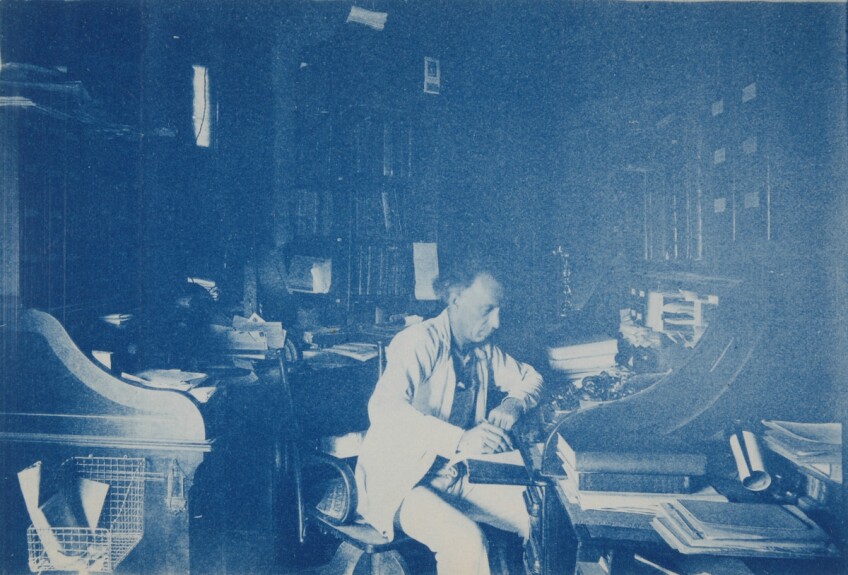

There’s no question that Lummis was magnetic by way of eccentricity, even by way of his arrogance. At various moments, he even claimed to have invented the cultural/geographical term “The Southwest” and the phrase “See America First.” But he’s more than showy self-promotion or phrasing. Today, we need to re-discover him, and his depth, in the Los Angeles he loved. Writer, publisher, editor, photographer, essayist, ethnographer, collector, museum founder, city librarian, bon vivant, Lummis kept himself remarkably busy for decades, spreading a gospel about indigenous and regional Southwestern history and culture, and his home,based mostly in Los Angeles.

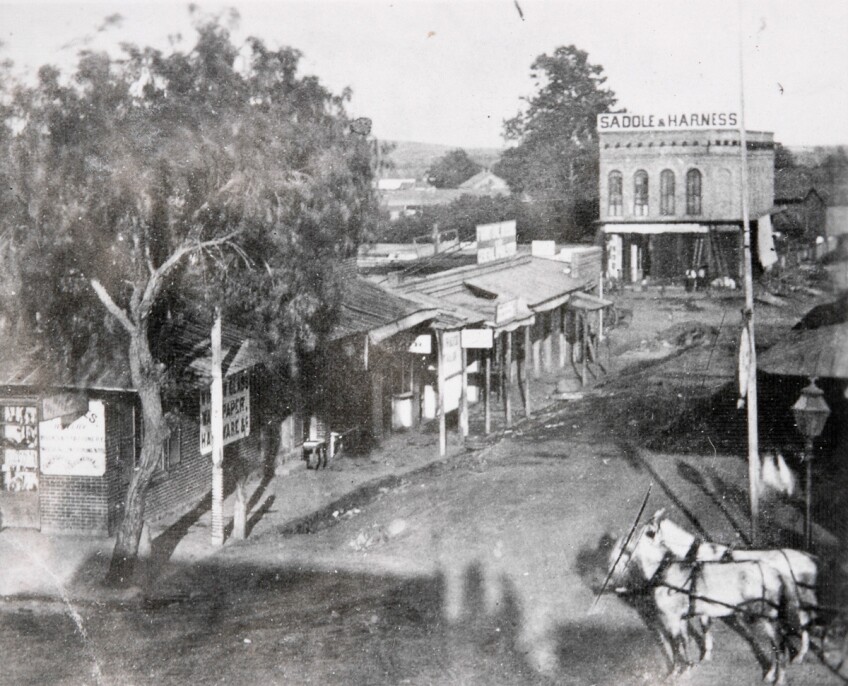

A New Englander by birth, Lummis dropped out of Harvard and briefly settled in Ohio as a poet and journalist. In the 1880s, he showed up semi-famous in Los Angeles, having spent half a year walking here. Along the way, he filed regular dispatches of his journey in the Los Angeles Times, which promptly hired him as city editor when he arrived. Thus began a life of letters and adventure in California and across the Southwest. Lummis ran the Los Angeles Library for a time, he took over the helm of the important regional magazine "Land of Sunshine," he was a self-taught ethnographer of the Pueblo peoples of New Mexico, and he tramped across the Southwest and down to Peru with anthropologist Adolph Bandelier.

With characteristic blazing energy -- he worked himself into strokes and blindness at moments in his life -- Lummis leapt to causes and issues of the day: Native American education and culture; restoration of the California missions; collecting basketry and other artifacts of indigenous cultures of the Southwest. He wrote important eyewitness and participant observer accounts of the Southwest, its landscapes, its religions, and its peoples. He built the Southwest Museum -- the first museum in Los Angeles -- and filled it with his own stunning collections. He made wax cylinder recordings of regional Mexican and indigenous songs, thus saving many from eternal disappearance. He took thousands of photographs, and he wrote thousands of letters. He chased women, he smoked, he drank, and he swilled coffee by the gallon.

For Lummis, Los Angeles was a kind of Santa Fe on the Pacific, a place in which older and even ancient traditions of Mexican and Native American populations could influence, and yet be held in regard by the rapidly urbanizing Southland. In some ways, his primary goal was to keep Los Angeles in the Southwest, to keep it tied to regional history, culture, and demography, even as it juggernauted its way to metropolitan, and eventually, global, ambitions.

As we re-discover Lummis, we’d best re-discover his home and the museum he created. Irrepressible and irascible, far from perfect, Lummis built his Arroyo stone home El Alisal in the Arroyo Seco with Indian friends at the beginning of the 20th century. A perfect regional expression of “arroyo culture” and our own arts and crafts sensibility, Lummis’ home is a testament to Lummis and his desire to do things, big things, from the ground up, things that spoke to the region and its historical and cultural complexity. He built the Southwest Museum at the same time, and both house and museum were born out of his desire to make powerful regional statements through architectural and material culture.

Its cultural importance notwithstanding, El Alisal today seems like an anomaly in the metropolis, a stone house but a stone’s throw from the Arroyo Seco Parkway. There’s nothing like it here in Southern California, and there’s really no one like Charles Fletcher Lummis. There really could only be one Lummis. But it is also true that the city left him behind and made his stone house look as a weak fortress against what the future held. Lummis was an unusual man, granted, but he’s been rendered all the more so because the world he expected for Los Angeles did not last. The movie industry, car culture, and skyscrapers -- and the millions of people who didn’t have his regional sensitivity and curiosity -- pushed Los Angeles out of the Southwest and into a different geography, as the new metropolis of western America perched on the Pacific Rim.

The new Los Angeles made the old Los Angeles look quaint, and it rendered Charles Fletcher Lummis quaint in so doing.

Since his death in 1928, his mythos is difficult to get past. It is difficult to breach so that we might pull Lummis free of it, or at least free enough so that he can mean more to us than easy parody of a dilettante, pinball of a man, careening wherever ego and curiosity took him. As it is, he’s often mentioned alongside a wink and a nod, a chuckle, or by way of simple assignment to the ranks of regional eccentrics. Up north in San Francisco, there was Emperor Norton, the self-proclaimed “Emperor of the United States” and “Protector of Mexico,” a mid-19th century figure around whom San Franciscans embraced as a colorful and somehow emblematic symbol of their city’s insouciance. In somewhat similar fashion, Los Angeles has Charles Fletcher Lummis. Norton had a saber and military regalia (and was mentally ill). Lummis had his signature corduroy suit, an ever-present cigarette, or even the occasional breechcloth. There’s Lummis, often shirtless, at work on some craft or project or another, proud of how he looked and what he was up to. Sybaritic to a fault, Lummis kind of gets in his own way in terms of legacy, and that’s both understandable and a shame.

Lummis was picturesque and picaresque. But he was more than that. Perhaps we should pull him back from the edge or boundaries of only that. Let me try an ill-advised comparison: Could Lummis be the Southern California version of Thomas Jefferson? Polymaths born about a century apart, Jefferson and Lummis shared lives fueled by insatiable curiosity. Here are two imperfect institution builders, men of letters and action and ideas, of often striking egalitarian impulses (and, to be sure, the opposite at times), and hungry to wrest meaning from histories -- human and natural. I write this knowing that this is saddling Lummis with more expectation than he can live up to, and might just be blaspheming Jefferson (rolling now in his grave) while so doing; but can we bring them into the conversation together, if only to drive the omnipresent shadow of Lummis' quaintness and his eccentricity away, if but for a moment?

Discover more about Charles Fletcher Lummis:

Lummis House: Where Highland Park's Herald of the Southwest Reigned over his Kingdom

El Alisal: Built Stone by Stone

Charles Lummis: Larger Than Life, A Self-Made Man

The Crusader in Corduroy, the Land of Soundest Philosophy, and the 'G' That Shall Not Be Jellified