Blurry Boundaries: New Architecture Exhibitions Survey Cross-Disciplinary Practices

Architecture, especially at its most conceptual, is murky territory. It takes a risk for the public to wade in. The field is routinely blasted for using alienating jargon or offering up sci-fi designs that produce head scratching. Three exhibitions on view right now across the southland celebrate experimental design, while making it accessible to a broad audience. Each show -- Almost Anything Goes: Architecture and Inclusivity at the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara (MCASB); Materials & Applications: Building Something (Beyond) Beautiful, Projects 2002 - 2013 at Cal State Long Beach University Art Museum; and Blindspot Initiative at the Keystone Gallery in Los Angeles--provoke a collaborative dialog about architecture and its allied disciplines: art, design, fabrication, and digital technologies. While the installations run the gamut from the scrappy to the institutional, when taken together these shows reveal a rich and diverse community united by an ethos to question both the academic and professional boundaries that surround architecture.

On view until April 13, "Almost Anything Goes: Architecture and Inclusivity" brings together six Los Angeles-based practices: Amorphis LA, Atelier Manferdini, Ball-Nogues Studio, Design Bitches, DO/SU Studio Architecture, and Digital Physical / Variate Labs. Organized by MCASB executive director and chief curator Miki Garcia and visiting curator Brigitte Kouo, the exhibition doesn't try for a larger formal narrative in order to link art and architecture, as attempted by the problematic "A New Sculpturalism: Contemporary Architecture from Southern California," which opened last summer as part of Pacific Standard Time: Modern Architecture in Los Angeles. Instead, each studio produced a work idiosyncratic to the practice.

Garcia suggests that each piece in the gallery corresponds to a unique trajectory. "Each designer was selected for this exhibition for the strength of their work, the purposeful way they continue to strive for new thinking, contributions to the field, and a certain courage to work on experimental terms," she explains.

The installation entitled "If looks could kill, I am dead now" (2013) by Ramiro Diaz Granados of Amorphis LA and Matthew Au, for example, investigates the blurry line between drawing and object. In the MCASB gallery, four oversized digital prints hang on steel armatures. The linework, which draws the viewer into an optical illusion, is a delicate as the steel frame is robust, as such, the frame is as important as the illustration it supports. There are common sources between each of the designers. Both Catherine Johnson and Rebecca Rudolph of Design Bitches and Elena Manferdini are inspired by pop art and the radical insertion of decoration into the pretty staid language of architecture, in the gallery, however, these influences manifest in different ways. Design Bitches' "Heavy" (2013) features puffy clouds made of cast concrete. While Manferdini's "Eye Candy Tables" (2012), true to their title, are organically-shaped tables printed with sweets in Candy Crush hues.

The MCASB sits at one end of the Paseo Nuevo shopping mall in downtown Santa Barbara and it is surprising to find such a diverse collection of commissioned architectural installations just blocks away from a Bath and Body Works. The location, however, reinforces the inclusivity in the exhibition's title. If almost anything goes, then everyone is welcome. "I think our current moment can be described as syncretic, flexible, and cooperative," says Garcia, reflecting on the present abundance of designers testing architectural ideas through alternative mediums like furniture, art, sculpture, and in the case of Digital Physical / Variate Labs's contribution, virtual reality. "Perhaps we are seeing the product of postcolonial conditions, globalism, and new technologies that are closing the gaps between disciplines, cultures, and modes of thinking so that for artists/architects today there is a wider pool of resources from which to work."

Similarly cross-disciplinary, the exhibition "Materials & Applications: Building Something (Beyond) Beautiful, Projects 2002 - 2013" documents designs that expand notions of architecture. Curated by Kristina Newhouse in dialogue with Jenna Didier, founder of the non-profit Materials & Applications (M&A), the exhibition on view until April 13 presents more than a decade of works and public programming developed for and in the gallery's modest "pocket park" space on Silver Lake Boulevard. In retrospect at the University Art Museum (UAM), M&A's series of full-scale outdoor installations, hands-on workshops, and community-driven programming adds up to an impressive oeuvre -- one way more influential than the modest courtyard space implies.

DO/SU Studio Architecture and Ball-Nogues Studio have work in Santa Barbara and in Long Beach. At first glance, the two projects by Doris Sung of DO/SU seem similar -- both employ thermobimetal, both are somewhat cylindrical with complex fabrication techniques, and both are full-scale prototypes. Sung's approach, however, changed according to each installation context. According to Sung, one is a sun-shading, self-ventilating application, the other, a structural proposal. "Bloom," a collaboration between Sung, architect Ingalill Wahlroos-Ritter and structural engineer Matthew Melnyk, was designed in 2011 for M&A's courtyard, where exposed to the elements, the 20-foot tall flower-like pavilion opened and closed its heat-responsive metal petals in reaction to the sun. (It's documented in the UAM exhibition via photos and drawings.)

"Using solar analysis tools and digital fabrication methods was invaluable to the development of my research," Sung explains. "Each day, the surface would curl open and closed as the sun's rays moved across the surface. The response was immediate." The temperature-controlled museum in Santa Barbara required a different approach. Sung used a thicker version of the heat-responsive aluminum, which curls at 350°F or above. "Heat was used during the assembly process as a way to ease construction and make a pre-tensioned surface. The result is a super strong surface that is lightweight."

Benjamin Ball and Gaston Nogues' practice sits at the intersection of architecture, art, and industrial design, with heavy doses of craft and fabrication thrown into the mix. It's an approach that emphasizes material research and design production. Their 2013 series "Radiant Body Globs," three luminous sculptures made from paper pulp, are on view in Santa Barbara. According to Ball, the globs are descended from the same structural basis of Maximilian's Schell, a digitally fabricated Mylar shade structure produced a decade earlier for M&A and documented in the Long Beach gallery. "Specifically, the Body Globs descended from the structural basis of the minimal surface," Ball explains. "To get a picture of this, imagine a child waving a ring to make a giant soap bubble, the soap bubble and all of its permutations are minimal surfaces."

For Ball, a definition of architecture is broader than any conventional act of building. His practice looks at a long history of production that came of age in Los Angeles: automobiles, aerospace, ceramics, and film. He speculates that this legacy drives much of the experimental design going on today. "Maybe its because California wasn't a hotbed of academic history and theory until late in the Twentieth Century," he ventures. "Designers weren't beholden to any traditions, so nobody was standing on the castle walls keeping the tinkerers, the entrepreneurial risk takers, and experimenters from jumping over. It was the people with a raw intuitive inclination toward making things that became visible."

One will find an emerging generation of experimenters in the Blindspot Initiative exhibition at Keystone Gallery. The show features a multidisciplinary group of ten artists, designers, and architects. Eight out of ten, however, have a background in architecture. Somewhere Something, a multidisciplinary design and fabrication studio founded by Biayna Bogosian, Jason King, and Sacha Bauman, and Jose Sanchez of Plethora Project curated the show, drawing on a number of the designers and makers with studios at Keystone Art Space on San Fernando Road in Atwater Village.

"I'm glad it's not a field of objects that blink," says King of the gallery full of artworks, artifacts, videos, and installations where the designers relied on computation and advance technologies as part of the developmental process. Zachary Schoch's gooey-looking vases, for instance, are the products of a robot he built himself to create large-scale 3-D printed objects. He first developed the robot as a thesis student at SCI-Arc. Built out of sections steel tubing and electronics, a MakerBot on steroids, it's housed down the hall in his studio. For "Aluvium" (2014), filmmaker Catherine Griffiths of Isohale combined video and coding to create a memorizing loop in which ecological data is processed, visualized, animated, and overlaid on desert landscapes.

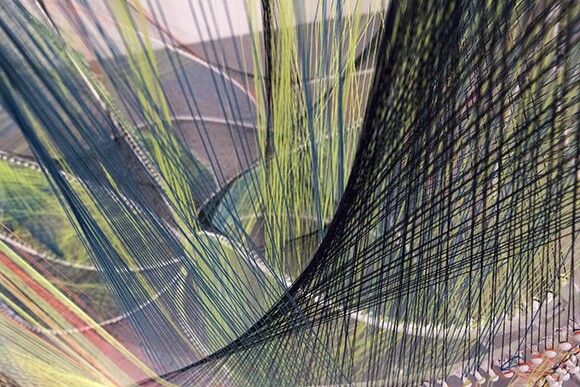

"DOT/O" (2014), Somewhere Something and Plethora's collaborative contribution, sits in the center of the gallery. An organically shaped steel armature covered in colored thread, the piece wills visitors to touch and engage the sculpture by weaving thread across the form. Inspired by game theory, there are very basic rules posted on the wall: "max span is an arm length" or "connect dots on alternate rods." The result of these simple instructions is a complex, collaborative (or crowd-sourced) sculpture.

The Blindspot Initiative exhibition closed on February 17, but the ideas provoked by the show live on in a series of spring workshops. Classes include game theory software, geo-data visualization, robotics, and prototyping using open-source Arduino electronics. By empowering designers to learn new skills, the organizers continue a legacy of blurring boundaries between disciplines.

Given the abundant production illustrated by these three exhibitions, it difficult to think of any stanch disciplinarian at the gates guarding the distinctions between architecture, art, and technology. Their interdependency has long been established. Still, operating in-between is murky and even isolating for designers looking for a toehold in the field. "It's not really possible to do what we do while firmly rooted in one territory," says Ball. "Perhaps these shows and others like them sanction this form of 'practice,' and frame the work for consideration within the profession." But perhaps these exhibitions do more than legitimate. By celebrating hybrid ways of working, the curators made visible a community of practitioners -- one that the studios themselves may not even have acknowledged -- to a wider audience.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.