Art and the Creation of a Resilient Japanese American Spirit

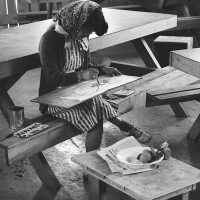

In a 1943 photograph of artist Chiura Obata, he gazes intently at his subject outside the picture frame, paintbrush in hand. He’s seated outdoors, his face in profile, his hair windswept. In the foreground two of his students, young boys, work on their own ink brush paintings, completely absorbed. Another photo of the same period, taken by Dorothea Lange, depicts a group of adults in Obata’s class bent over makeshift tables.

These children and adults were students in art classes that Obata, along with artists George Matsusaburo Hibi and his wife Hisako, organized at the Tanforan Detention Center in San Bruno, California. All of them were among the 110,000 people of Japanese descent who were rounded up and evacuated from their homes following the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. Given just days to settle their affairs, they were ordered to bring only what they could carry when they reported to assembly centers. They fell prey to ruthless speculators, losing farms, retail business, professions and their sense of place in the community.

The Obatas and Hibis were among the countless artists who found their lives shattered, shunted behind barbed wire. Some of them went on to achieve fame, like sculptor Ruth Asawa, furniture maker George Nakashima, automotive designer Larry Shinoda or graphic designer Sadamitsu “Neil” Fujita. As a group, they exerted an outsized influence on American art and design, and yet rarely spoke of their incarceration experience. These artists and designers are the subject of the “Artbound” documentary “Masters of Modern Design: The Art of the Japanese American Experience.”

As soon as FDR issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing the forced removal of west coast Japanese, Obata, a well-established artist, “saw that this was a mistake and would be a terrible burden on the community,” says Kimi Kodani Hill, Obata’s granddaughter. He began planning an art school that would keep prisoners occupied and lift their spirits. The Hibis, who had been trained at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute), modeled the Tanforan art program on the curriculum there.

Within a month of arriving at the former racetrack, the Tanforan Art School, located in Mess Hall number 14, was up and running. Classes were taught by 16 inmate artists, whose ranks included Mine Okubo, then a prizewinning Cal fine arts graduate who later published her frank depiction of the prison camp experience, “Citizen 13360.” Obata’s wife Haruko taught ikebana, or Japanese flower arranging.

By the time the Tanforan detention center closed six months later and its 7,800 inmates were transferred to the Topaz concentration camp in Utah, the school had offered 95 different art classes to over 600 students. It quickly reopened at Topaz.

“There were classes for every age from preschoolers all the way up to seniors, and on every subject,” says writer Delphine Hirasuna, who has written about the art of the prison camps. Sketching, watercolor, sumi-e (Japanese inkbrush painting) and vocational arts were among the subjects taught. “One of my friends showed me the fashion patterns that her mother made in camp, a whole impressive scrapbook of them,” Hirasuna recalls.

As a 14-year-old, Obata had run away from his home in Sendai, Japan to study art in Tokyo. When he arrived in San Francisco in 1903 at age 17, he was already practiced in both traditional and modern Japanese artistic styles. By the outbreak of World War II he had had successful careers as an illustrator and designer. His work had been exhibited in Japan and the US, and he was a highly esteemed UC Berkeley art instructor.

To open the art school, Obata had worked closely with camp officials, and when dignitaries visited, he would be called upon to give art demonstrations. It was this closeness with authorities, says Hill, that led to a late-night attack on Obata by a fellow prisoner. At the time, all of America’s ten concentration camps were in turmoil, torn by disagreement over the so-called “loyalty questionnaire,” which the government had issued to separate prisoners who wanted to stay in the U.S. from those who wanted to be repatriated to Japan. Resentment and resistance followed, as well as bitter divisions within families and among friends.

Hit on the face with a lead pipe, Obata spent 19 days in the hospital, after which he and his family were granted permission to leave the prison and relocate to St. Louis, where his son Gyo was living. Gyo had managed to avoid imprisonment by transferring from Berkeley to continue his architectural studies at George Washington University. He remained in St. Louis after the war, eventually becoming a founding partner of the global design firm HOK.

Later, Gyo Obata recalled the strangeness of visiting his family in the concentration camp during vacations from school. “It was just crazy,” he told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “I was a free person, and they were like prisoners.” Other sad ironies abounded. Uniformed members of the U.S. armed services visited their parents in the prison camps while on furlough, and as the war wore on, more and more families mourned the deaths of sons who had been killed fighting for the U.S. while they themselves languished in U.S. prison camps.

Among the artists imprisoned were a number of illustrators from the film industry, says Hirasuna. At the Santa Anita detention center, a group of illustrators — Tom Okamoto, Chris Ishii, and James Tanaka — would sit up in the race track grandstands, drawing. Ruth Asawa, still a teenager then, loved sitting with and learning from these professionals.

In her 2005 book “The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946,” Hirasuna collected prison camp artwork ranging from painting, prints, sculpture, flower corsages made from shells and miniature Buddhist shrines. The Japanese word gaman means "enduring what seems unbearable with dignity and grace.”

The book grew out of Hirasuna’s own discovery of a carved wooden bird pin, made while going through her mother’s garage following her death. She began collecting prison camp artwork from friends in her Lodi, Calif. neighborhood, which grew in scope as offerings poured in from former internees and their families around the country. The objects have been exhibited at 15 museums, including the Smithsonian’s Renwick Art Gallery and the University Arts museum in Tokyo.

“Amazing things came out,” says Hirasuna. “More than the fine artists like Obata and [painter Henry] Sugimoto, I was blown away by the quality and the creativity of people who had never done any art, the fishermen and the shopkeepers. This was a way to pass the time in the camps. They worked at it every day, and they taught each other.”

For both amateur and professional artists, the end of the war and the return to the outside world brought new hardships. Many prisoners had no choice but to abandon their artmaking. There was the farmer who had created “museum quality stuff,” Hirasuna recalls, “who just stuck everything in a shed and went back to farming.” Once free, “they had no time, no place to live, and no jobs. The last thing on their minds was creating art,” she adds.

One prisoner, Homei Iseyama, had come to America to study art. At Topaz he created a series of exquisite carved slate works but, says Hirasuna, “he was one of those people who never got to realize his talents,” becoming a landscape designer after the war. George Matsusaburo Hibi and his wife relocated to New York City in 1945, but his health — which Hill says her grandfather Obata “really felt was compromised by being in the prison camps” — gave out. He died of cancer two years later. To support herself, his widow Hisako worked as a garment factory seamstress, eventually achieving success as an artist decades later.

For years after the war the imprisoned artists rarely spoke of this chapter of their lives; for many it was a traumatic event that stirred feelings of shame, humiliation or anger. Hirasuna recalls a well-known Japanese American designer who, when he found out about her book, “was concerned that I was stirring up a can of worms. He said, ‘Don’t do it, you don’t want to go there.’” Later, she learned that his father was one of about a thousand Issei (first generation) men arrested by the FBI right after Pearl Harbor and that a cascade of tragedies had befallen his family. Hirasuna believes that the reticence of former prisoners to talk about the camps with their children sprang from a desire to protect them and prevent feelings of bitterness and anger. “They wanted their kids to be proud of being American."

In the 2018 book “Chiura Obata: An American Modern,” editor and art historian ShiPu Wang writes of Obata, “Only in the last decade has his art regained visibility,” even though he “helped shape the California watercolor school” that later influenced Bay Area visual and literary arts like Jay DeFeo, Gary Snyder and Sam Francis.

When the Whitney Museum of American Art introduced its sleek Renzo Piano-designed downtown building in 2015, it mounted a show of works from its permanent collection intended to recast the American canon by featuring previously overlooked artists. Included was an exquisite set of prints by Obata, made in Japan using traditional woodblock printing techniques, but depicting scenes of Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada. The Whitney called his woodblock works “virtuosic in their craftsmanship.”

“He would always say that nature was the greatest teacher,” says his granddaughter Hill, recalling one image that Obata painted over and over after evacuation and through his old age. It was of a giant Sequoia, or very old and gnarled Monterey cypress, buffeted by large winds, but somehow standing straight, with dignity and strength. “He did that tree in the storm one after another right after evacuation,” says Hill. He would dedicate it to the glory of struggle or some title like that. I know he was referring to those Issei friends who somehow survived, or maybe didn’t survive. The beauty of their lives were like these trees: they had survived so much.”

In a 1939-40 Berkeley alumni magazine Obata wrote, “I always teach my students beauty. No one should pass through four years of college without being given the knowledge of beauty and the eyes with which to see it.” He taught his students in the concentration camp to see beauty in the harsh landscape that surrounded them, and he taught them to do three things before they even put brush to paper: compose their minds, correct their postures and regulate their breathing. “The mind must be as tranquil as the surface of a calm, undisturbed lake,” he wrote of his method.

“Nature was his inspiration,” says Hill. “It’s easy for me to see how in the cold barracks teaching people to focus and really observe nature would help them take their minds off their circumstances.”

As Ruth Asawa observed after the war, “Art saved us.”

Manzanar viewed from the guard tower | Ansel Adams, War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement via Densho.org