Artist and Signpainter Preserves Memories of East L.A.'s Overlooked Artifacts

Los Angeles-based visual artist Alfonso Gonzalez Jr. has long felt the changes in his surroundings. "I think it is sad that we're losing these different nuances that make places beautiful and interesting and have this character and culture," said Gonzalez Jr. "I'm trying to capture this moment in time because I feel like this is one of the last moments that things will look and feel the way they do."

Gonzalez Jr.'s work preserves public spaces and fixtures of L.A. in his landscape art, embodying worn surfaces aged with years of embedded memories, cracks and fragments of paint chipped over decades.

His pieces serve as commentaries on displacement — the profound shifts that seep into gentrifying areas, while celebrating the physical artifacts these communities hold close.

In his first solo exhibition, "There Was There" held this year at Matthew Brown Gallery, Gonzalez Jr.'s work focused on the neighborhoods between his East L.A. home and Boyle Heights studio, capturing an assemblage of objects that make up a community: an Aztec calendar set on a liquor store or the embroidery of a charro belt with roosters engraved as a frame. The words "El Norteño" are painted next to tags, aligning multilayered identities.

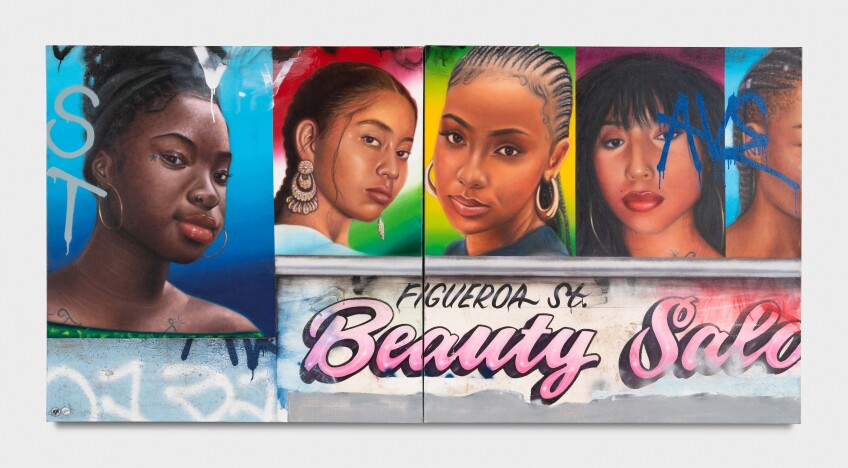

A large-scale painting, "Magic Beauty," is embossed with bold, three-dimensional text that reads "Beauty Salon." The hand-lettering replaces the static digital neon signs that invade commercial outlets. On it, he sets promotional fliers of local businesses and concerts against exposed brick and multi-colored walls. Red long-stemmed roses, a caricature of Minnie Mouse and hands displaying nail art complement sharp-angled graffiti tags. The painting is rendered with such realism it could be mistaken for a photograph, were it not mural-sized. "I am fascinated by people's decisions and how they influence surfaces," said Gonzalez Jr.

Making Marks: Graffiti and Sign Painting

Gonzalez Jr. grew up in Avocado Heights, an unincorporated equestrian town in San Gabriel Valley. It was the '90s. Hip hop and different types of graffiti reigned supreme.

His dad Alfonso Gonzalez Sr. was raised in Tijuana, moving to East Los Angeles' City Terrace in the 1970s, while his mother, whose family had a ranch in Guanajuato, Mexico, later resided in Boyle Heights. The father, a commercial sign painter by trade, traveled in and out of different pockets of Southern California en route to job sites, from the San Fernando Valley to South Los Angeles and Northeast Los Angeles, taking young Gonzalez Jr. with him.

It was during these experiences that Gonzalez Jr. became fascinated with the range of graffiti that claimed walls on highways. He recognized how invisible territories and boundaries were marked by gang graffiti. This division mapped stories and communication, crossing barriers and geographies that sparked a deeper look at the city's disparities and cultural aesthetics.

"All of this informs what I am doing now," he said. "I started noticing gang graffiti and how it separates neighborhoods — and landmarks too."

Gonzalez Jr. brings the disparate aspects of his Avocado Heights upbringing, non-institutional artistic expression and the Chicano mural movement into his art. He was moved by the various genres of graffiti culture, including the mechanics and choreography that went into creating murals or throw-ups (a reference to a graffiti writer's name on a wall). "The [ability to reach] crazy ledges and bridges were always mind-blowing," he shared, and the scale of much of the work left an impression. His cousin, a tagger, gave him access to graffiti's clandestine world. He was also introduced to the art of lowrider culture by his father's friends and Mexican muralism by Los Four and the East Los Streetscapers.

As a youth, Gonzalez Jr. experimented with other creative outlets, resisting anything that didn't have to do with art. "It came naturally," he said. After high school, he attended Los Angeles Trade Tech College for sign graphics and moved to San Francisco after graduation. Gonzalez Jr. decided to pursue art as a career but didn't know where to start. "I had an opportunity to work for a company in L.A. painting large advertisements and I started painting billboards, and then eventually painted walls," he said.

He began as an apprentice, then transitioned to an assistant, gaining confidence in portraiture. He also worked throughout the U.S., gleaning information from his travels. Gonzalez Jr. approached his practice as a study. He visited museums in every state, exploring the systems and ideas in contemporary art while also learning the business side of sign painting.

"I was putting a lot of effort into different companies and people, and I did so much that I never thought I could do," he said. "I did everything on my own: mix paint, pick up the scaffold, find the wall, get the U-Haul and then paint. It was like a construction art school."

I realized one of the most important things I wasn't allowing myself to do before was make bad art. I was so afraid.Alfonso Gonzalez Jr.

While in the commercial space, he experimented with black and white palettes, testing different techniques for his own work. An early portrait of a paletero (ice cream vendor) incorporated texture, twigs and dirt from his backyard and foam spray. "Before, I wouldn't do anything that looked realistic; it was more cartoon, weird or abstract," he said.

In 2018, after about six years as a professional sign painter, Gonzalez Jr. decided to invest fully in his artistry, even turning down a recent promotion. He converted the laundry room in his East L.A. house into a studio and only took on a local job for a friend, still doing the same line of work, but it was once a month. These changes afforded him the time and space to dive into art making. "I realized one of the most important things I wasn't allowing myself to do before was make bad art. I was so afraid," he said.

Paying Homage to Neighborhoods

Most of Gonzalez Jr.'s subjects are from working-class communities — which emanates from his connection to the people and interactions within these areas. "There's so much rich culture within these neighborhoods," he said. "If you exclude that, you're doing a disservice to the city's history." His work seeks to archive the physicality prone to change, like an exterior that cultivates a specific style and flavor or walls, sometimes weathered from the sun, altered and naturally reworked.

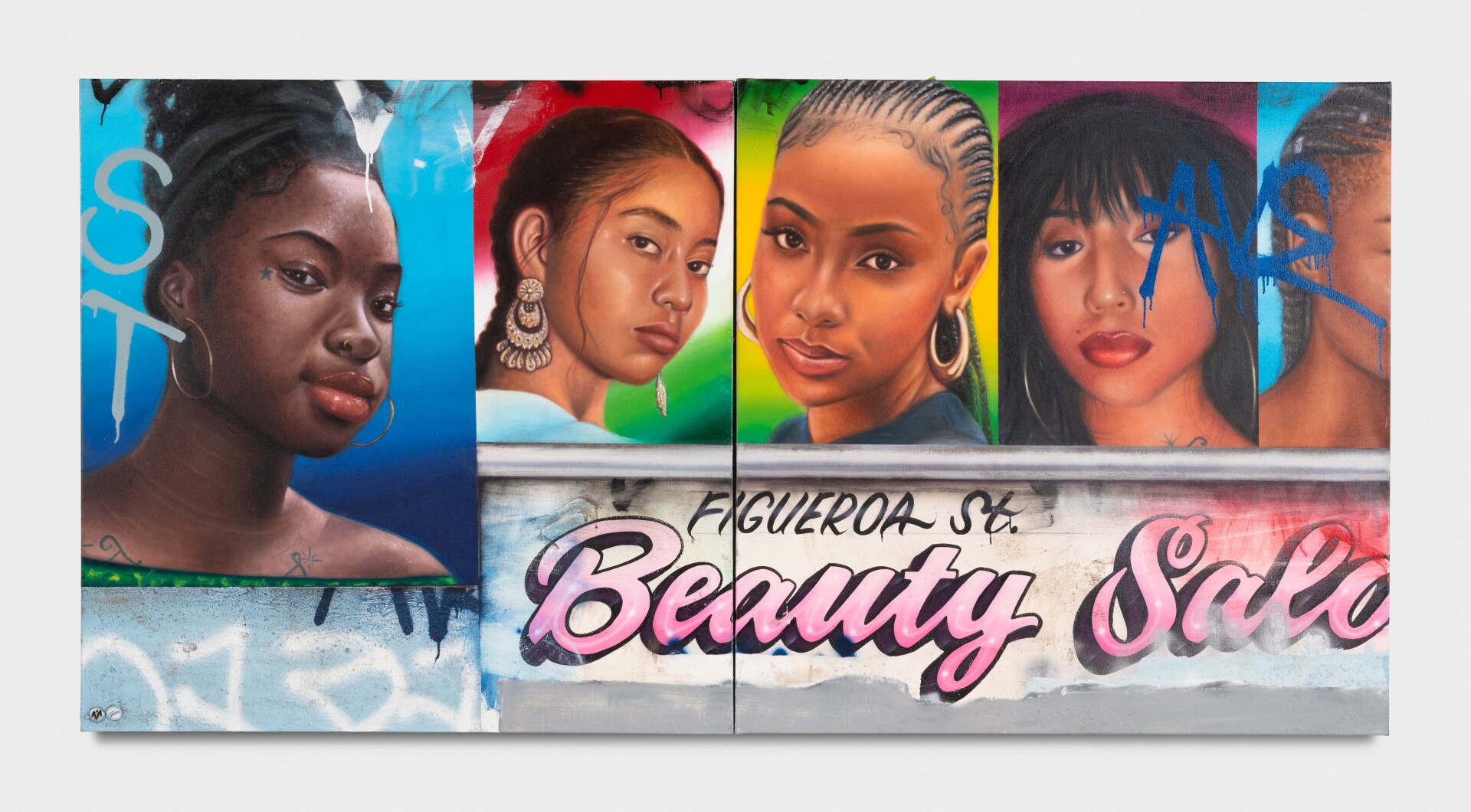

Gonzalez Jr. observes his environment, creating compositions with a sign painter's sensibility. He will often recreate an image into a collage. "Some of my work is a literal landscape, with a tree and a sky, and some of it is more zoomed in to a particular subject," he said, describing his method. "When I incorporate portraiture, it's more of a façade, like an ad on the side of a building," producing an illusion that a person is standing there. Within the still lifes, Gonzalez Jr. unearths quotidian experiences or interactions that trace back to the feeling of the people that lived there or participated in the creation by integrating sourced paper posters onto the canvas, for example. "It is interesting how a landscape, an object or a surface can tell so much without knowing the story," he said. "Something I think about is my legacy and my work living way beyond my lifetime."

Adding to the Art Canon

Not only does Gonzalez Jr. want to convey the feel of his community, the artist also wants his personal narratives reflected. "When thinking about art history and portraiture of people and horses, it's all white men of power, like colonizers," said Gonzalez Jr. "I wanted to add my experience to the art history canon." He does this in subtle ways (like adding a spray painted tag on the corner of a painting) or creating a life-sized painting "Sueños" (2021), which was a part of a group exhibition "Shattered Glass" at Jeffrey Deitch Gallery. Based on a reverie of his hometown Avocado Heights, a primarily Mexican community that participates in ranch culture, the painting portrays a person on a horse donning a white tee, dark denim pants and Locs sunglasses, peering down at their phone. It offers a reclamation of heroism.

Another work in the show, "El Pato" (2021), assesses pop art and familiar hangouts. An El Pato facility sits on the edge of the L.A. River, a marker with exposed brick cladding and their signature branding cast along fences. Gonzalez Jr. captures the empty stretch behind the factory as a haunt for locals, car clubs, bikers and even daytime raves that overlook downtown L.A.'s cityscape. He memorializes this space on canvas with a can of El Pato hot tomato sauce at the forefront of a clay-colored wall.

Themes of erasure are, in part, his purpose. "A lot of the things that I sort of took for granted and grew up admiring, consciously or subconsciously, are disappearing," he said. "The mom-and-pop businesses are different, murals and signage." In "L.A. Real Estate 1 & 2" (2022), corner houses sit before the infiltration of wooden fences, with windows boarded and the exploitative signs "We buy any cash." Electrical lines weave into different directions with a pair of kicks dangling from the cords, and roadside memorials marked with candles and flowers honor the deceased.

With his art, Gonzalez Jr. documents the signs and sights of a place amid transformation: home. He continues to share these stories visually, expanding his audience and practice with upcoming group shows in Hong Kong and Sweden. He also plans on taking everything at his own pace. His work "Mickey's Liquor" (2019) is currently on view for "Loveline" at the Long Beach Museum of Art and "Say No More Fam" (2022), is now part of the Institute of Contemporary Art Miami's permanent collection.