A History of Opera in Los Angeles

Opera in Los Angeles: An Unlikely Beginning

In the late 19th century, opera didn’t have strong a foothold outside a few big cities such as New Orleans and New York. The rest of the country experienced opera occasionally and primarily through touring companies that crisscrossed the nation by train. In 1897, with a population of less than 100,000 people, Los Angeles wasn’t a particularly notable destination for these companies. Yet somehow the city managed to make a bit of operatic history: In October of 1897, Puccini’s beloved opera “La Bohème” had its American premiere at the Los Angeles Theater on Spring Street.

The critics of the era enjoyed the production, presented by the Del Conti Italian Opera Company on its way to San Francisco after touring Mexico. But only 532 people showed up on the opening night at a theater that sat 1,200. Fortunately, this small turnout did not seal the fate of opera in Los Angeles. Touring opera companies continued to stop in the City of Angels, introducing Los Angeles to an artistic medium that gradually evolved into a cornerstone of L.A.’s arts culture.

The Rise and Fall of Opera in the Roaring Twenties

Touring companies, like the Maurice Grau and San Carlo Opera companies, were the city’s primary source of opera for many years. They found success in the early twentieth century producing everything from “La Bohème” to Richard Wagner’s “Lohengrin.” But, the city still lacked a resident opera company.

Following the opening of San Francisco Opera in 1923, founder and General Manager Gaetano Merola sought to create a sister company in Los Angeles, so he could offer longer contracts to the star singers of the era. In 1924, the Los Angeles Grand Opera Association was born, presenting its first opera – Umberto Giordano’s “Andrea Chénier” – in the Philharmonic Auditorium (and later Shrine Auditorium). This marked the debut of two of the greatest singers of the era, soprano Claudia Muzio and tenor Beniamino Gigli, who would return to sing with the company many times over the next decade. The rest of that season included Massenet’s “Manon,” Gounod’s “Roméo et Juliette,” Mascagni’s “L’Amico Fritz,” Puccini’s “Gianni Schicchi,” and finally Verdi’s “La Traviata.” The latter show, which starred Muzio, was sold out, prompting the Los Angeles Examiner’s headline, “Opera Season Closes In Triumph.”

The finale of this first season cemented the company’s status. Throughout the Roaring Twenties, the Los Angeles Grand Opera Association (under Merola and later General Manager Richard Hageman) brought the best of opera to Los Angeles. Several singers from principals to the chorus were engaged from the Metropolitan Opera and the best companies in Europe. Famous French soprano Nino Vallin made her American operatic debut with the company, while soprano Lily Pons and tenor Francesco Merli were first seen on the west coast in roles at the company. It was a great time for opera in Los Angeles.

Then came the Great Depression. Audiences dwindled and the company could no longer afford to hire the star talent it was known for. Unable to compete with the grandeur of its earlier seasons and after a lackluster season in 1934, the Los Angeles Grand Opera Association was forced to close its doors.

The Los Angeles Civic Grand Opera Years

Once again, Los Angeles had no resident opera company, but the hunger for opera remained. Touring companies (who never stopped coming to Los Angeles even when there was a resident opera company) continued bringing opera to the city. While the San Francisco Opera and the Metropolitan Opera would tour their productions to Los Angeles for decades, there remained a lingering desire to return to the days when Los Angeles had its own company. This spurred Hollywood furniture maker Francesco Pace into action – and the seed for LA Opera was planted. In 1948, Pace founded the Los Angeles Civic Grand Opera Association in a church hall in Beverly Hills. The opera company had limited resources, often performing with only a piano. What mattered to Pace was the ability to produce shows in Los Angeles and to foster an appreciation of opera in the wider community. Rumors abounded that Pace continued crafting furniture for film sets and his elite Hollywood clients to support his vision and his own “opera habit.” Through the 1950s, Pace’s company grew and moved its staged productions to a more permanent home at the Wilshire Ebell Theater.

During one fateful 1960 production of Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro,” a young Bernard Greenberg sat in the audience with his wife Lenore. Greenberg was so enchanted by the performance that he readily agreed when a classmate suggested he join the opera board as treasurer. As he recounts now, Greenberg often never saw the second act. He would vanish into the box office at intermission and tally up the ticket sales to ensure he’d be able to pay the performers.

The Los Angeles Civic Grand Opera continued through the early 1960s. However, the arrival of the new Music Center was about to change the way Angelenos would experience the musical arts. The Music Center was a project championed by Dorothy Buffum Chandler since 1955, in the hopes of providing the Los Angeles Philharmonic with a permanent location in which to perform. The Dorothy Chandler Pavilion was completed in 1964 and the Los Angeles Grand Opera got its first permanent home as its resident company.

Francesco Pace had stepped down as head of the company by then, and board members hired other artists keen on making their mark in the growing Los Angeles opera community. Among these was artistic director Peter Ebert, whose father Carl had been the director of what is now the Deutsche Oper Berlin in the 1930s. The conductor Henry Lewis became the company’s new musical director, convincing members of the Music Center Association that the company should have the opportunity to perform there.

Opera Revolution

Bernie Greenberg would later remark how young all the members of the opera company were during this initial residency at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. During a time in history when the world was experiencing the rise of youth culture and monumental change, the evolution of opera in Los Angeles began. They did not have a significant amount of financial resources and they did not think much about the future, but the members of Los Angeles Grand Opera were audacious. They were hungry to express themselves, both artistically and culturally, through opera.

And they did.

During the 1965/66 season, the Los Angeles Grand Opera staged three productions: “Madame Butterfly,” “Don Giovanni” and Rossini’s “L’Italiana in Algeri” (starring Marilyn Horne). Despite the moderate success of these original productions and the creative enthusiasm behind them, the Music Center board members (including head Bill Severance) decided to focus their energy on creating a larger symphony. Dorothy Chandler appointed new key creatives to the opera board, including Ed Carter and John MacCone. With these decisions, the era of the Music Center Opera Association began.

An important development in the “staging” of Los Angeles Opera, the Music Center Opera Association spent the next two decades presenting touring companies, rather than creating its own productions. Partnerships with San Francisco Opera and ultimately the New York City Opera allowed the organization to showcase talent from around the world. Between 1967 and 1979, New York City Opera’s biggest star, Beverly Sills, performed regularly on the stage of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion with that company, starring in 17 different operas. The company’s eclectic offerings even included the 1966 west coast premiere of Alberto Ginastera’s “Don Rodrigo,” starring a then-unknown Spanish tenor named Plácido Domingo. It was his first performance in Los Angeles, and he never forgot it.

The Age of Major Opera Companies

With the retirement of Beverly Sills from the stage in the early 1980s, however, the association with New York City Opera entered a limbo. This is when two major events happened in the history of opera in Los Angeles.

The first was the redirection of the Long Beach Grand Opera under Executive Director Michael Milenski. Originally founded in 1979, the company’s early growth years consisted of presenting opera stalwarts, such as Verdi’s “La Traviata.” However, under Milenski, the company shifted gears. It emerged in the 1980s as an operatic innovator, staging productions that were anything but mainstream and that spoke to contemporary audiences, such as Benjamin Britten’s “Death in Venice.” This direction became a calling card for the company, which is still known for championing little known or new works. (In June, the company will host the SoCal premiere of Robert Xavier Rodríguez’s “Frida” about the legendary Mexican artist, for example.)

The second was the founding of LA Opera, which proved to be an Olympian feat indeed. With the 1984 Olympics set to arrive in Los Angeles, the timing seemed perfect.

In the early 1980s as the city prepared to host the Olympic Arts Festival in 1984 (as part of the Olympics), Los Angeles began a cultural renaissance. Organizers strove to prepare for the artistic invasion to come. The fate of the city’s opera company was in the hands of three visionaries: Bernie Greenberg, Music Center president Michael Newton and—most remarkably—Plácido Domingo, who had become a superstar in the years since his L.A. debut as “Don Rodrigo.” During the Los Angeles Olympics, the Opera Association co-produced three operas with London’s Royal Opera (“Turandot,” starring Domingo as Calaf, as well as “Peter Grimes” and “The Magic Flute”), which not only helped establish the city as an international arts destination, but also helped raise funds for the soon-to-rise opera company.

With renewed vitality, the Los Angeles Opera board hired famed artistic administrator Peter Hemmings to be the founding general director of what was then known as the Los Angeles Music Center Opera. Domingo took on the role of artistic consultant and committed to appearing regularly with the company. Hemmings brought years of successful experience working with both established and nascent opera companies and his direction proved to be vital in getting the company off the ground.

To create opera that was in tune with the community, Hemmings formulated an inaugural season that included large-scale successes, such as that inaugural production of “Otello.” It was followed by a lavishly traditional production of Puccini’s “Madame Butterfly” starring Leona Mitchell; an iconic production of “Salome” starring the unforgettable Maria Ewing; a staging of Handel’s Alcina at the Wiltern Theater; and one of the greatest works in American music, George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess.” While opera companies had historically played it safe in their inaugural seasons, Los Angeles Opera immediately strived to go beyond the traditional, and into truly grand territory.

For the first time since the 1930s, Angelenos had a major resident opera company. They could experience groundbreaking opera that pushed the boundaries of the opera. That is still true today.

Opera Today

For decades, LA Opera and Long Beach Opera have produced exciting works on either end of Los Angeles County, while also sharing opera with audiences through education and community engagement programs.

Merging the live aspect of seeing opera with the latest technology, LA Opera hosts yearly live broadcasts of its operas at Santa Monica Pier and other venues across the county attended by thousands. Through its Off Grand series, LA Opera also brings newer works to venues across the city. In June, LA Opera and Beth Morrison Projects will stage the west coast premiere of “Thumbprint“at REDCAT, an opera about how one girl changed the course of history in Pakistan. (In October, the Ford Theatres in association with LA Opera are bringing the virtual reality opera experience “Hubble Cantata” to L.A.)

In recent years, other companies have sprung up that have redefined the way audiences experience opera in Los Angeles.

The first of these companies, Pacific Opera Project, was founded in 2011 with the mission of planting opera firmly in pop culture and making it more accessible. Since then, POP, has become a Los Angeles gem producing operas in venues across Los Angeles, sometimes taking the form of dinner theater, as with its popular hipster take on Puccini’s “La Bohème.”

Led by Yuval Sharon (currently a resident artist at the LA Philharmonic), The Industry takes a different approach to experiencing opera, often making Los Angeles the backdrop for its productions. The company’s most recent project, “Hopscotch,” was presented entirely in moving cars traveling through the city’s traffic, garnering significant international attention along the way.

Today, Los Angeles is brimming with opera that expands the boundaries of the medium. So, it is fitting that the first ever made-for-TV-and-online opera will be released online by L.A.’s KCET on May 31 and broadcast on television June 13. “Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch’s Accuser” is an episodic opera that explores treatment of women diagnosed with “hysteria” over centuries. It’s an ambitious work shot in various locations around the country (including Alcatraz) and envisioned as an episodic work perfect for the Netflix-binge watcher.

In over a century, the way people experience opera has shifted. Opera continues to evolve as society, technology, and the way in which audience’s experience entertainment continues to expand. First, there were touring companies that performed occasionally, then resident companies that established a home for the art form. As the world of repertoire and performing companies have changed, so has the way in which fans experience opera. From live performances, to recorded performances and viewable on demand and online. While you often hear that opera is a dying art form, the opposite is true in the City of Angels. There’s something for everyone and it’s an exciting time for opera in Los Angeles.

Presented by LA Opera and Beth Morrison Projects, “Thumbprint” runs from June 15 to 18.

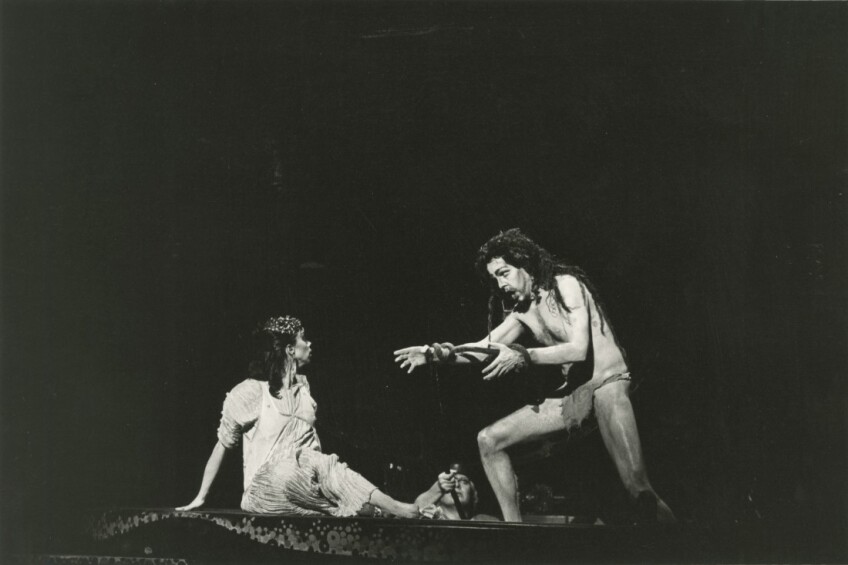

Top Image: A scene from the 2014 premiere production of "Thumbprint" | Noah Stern Weber / Beth Morrison Productions