A Different 1%: Veteran Artists and the Ghosts of War

"Fallujah" is the first opera on the Iraq War. Artbound documentary "Fallujah: Art, Healing, and PTSD" explores how the experience of war was transformed into a work of art. Watch the episode's debut Tuesday, May 24 at 9 p.m., or check for rebroadcasts here.

How does it feel to go to war? What does it feel like to come back? With less than one percent of the U.S. population in the armed forces, how are artist-veterans making bridges for a public that’s increasingly disconnected from the consequences of war? Is it ever truly possible to "come home?"

Every war delivers a raft of new technologies, injuries, and artworks.

The American Civil War produced multiple amputations courtesy of a spinning bullet that ground bones “almost to powder,” as well as some of the first major war photographs. In the First World War, heavy artillery shrapnel mangled soft flesh. Advances in medical science kept severely wounded troops alive, and veteran artist Otto Dix recorded the nascent plastic surgery and sensory prosthetics that tried to give them back a life.

The signature wounds of Iraq and Afghanistan troops are Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), clinical depression, and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). Although 22 veterans kill themselves each day, there is, as yet, no Defense Department recognition of "moral injury," the “bruise on the soul” that Michael Castellana, psychotherapist at the U.S. Naval Medical Center in San Diego, has attributed to “what happens when we send our children into a war zone and say, ‘kill like a champion.’”

For artist and Gulf War veteran Mark Pinto, the crux of his artwork is this “moral injury,” a phenomenon that shares symptoms with PTSD, but is not the same thing. “You can get PTSD from a car crash,” says Pinto in a recent conversation, “but you haven’t done anything that goes against societal norms. With a moral injury, you’ve done something, seen something, or know something that you shouldn’t have to see, know, or do.”

For Pinto, art therapy is not enough: “I honor and respect art therapy work,” he says, “but at the same time I want to transcend it. Many of us, we feel an obligation to share what we have learned. If I can personalize this moral injury and make it visceral, if non-veterans understood their complicity in war, something might change?”

Like Pinto, there is an emerging generation of American veterans who are acting on the idea that their work can help to heal not only its viewers and participants, but also wider societal wounds.

Utilizing multiple channels to broadcast and connect, these veteran artists tend to be individual makers of diverse objects -- including ceramics, installations, photographs, drawings, prints, and posters -- who also embrace the interaction, intervention, and activism that has come to be called “social practice.” When the subject of art and military veterans is discussed these days, it is usually in the context of therapeutic activities for people struggling to heal from the often-invisible wounds of war. Setting aside artists whose military service may be coincidental to their art-making -- like vets Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Sol Lewitt, Richard Diebenkorn, and even the popular TV painter Bob Ross -- art therapy focuses on benefit for the individual patient rather than on the quality of the artwork. The Art of War Project, which aims to use “art to help veterans with PTSD,” is a case in point. As its founder Curtis Bean says: “There are [more] healthy and positive options than medicating or self-medicating. You’ve just got to find the right option for you.”

In Pinto's work “Small Arms,” a mandala-like print of word-filled rifles and grenades, the artist says he was “referencing the morals you are raised with,” not least the commandment “thou shalt not kill.” A former Buddhist priest, Pinto says the mandala is “a map of the spiritual world and a focal point for meditation.” As the public gets farther and farther away from the actual fight, he says, the military “are isolated, and feel that they’re becoming expendable."

Iraq War veteran and singer-songwriter Jason Moon echoes Pinto's sentiments with his song “Trying to Find My Way Home:”

“How do they expect a man to do the things that I have, come back and be the same? The things I done that I regret, the things I seen I won’t forget in this life and so many more.

And I’m trying to find my way home, the child inside me is long dead and gone, somewhere between lost and alone, trying to find my way home.”

Telling a visual story in which a troubled veteran chooses writing over suicide, one of Moon’s viewers has written: “Tragedy rips out that innocence the void of losing it changes a persons mind, heart and soul. I feel like steel beaten, burned and forged into something I never should of been… One thing to be said song like this gives me hope that am not alone...”

Comparatively few in number, veteran artists often collaborate in a web of overlapping collectives.

The Dirty Canteen is a nine-artist collective that works to promote “understanding of how war and trauma not only affect members of the military, but our society as a whole.” Its members -- Pinto, Amber Hoy, Ehren Tool, Thomas Dang, Aaron Hughes, Jesse Albrecht, Daniel Donovan, Ash Kyrie, and Erica Slone -- have all exhibited or collaborated with San Francisco-based Combat Paper (CP), a project initiated by Drew Cameron, which has been “transforming military uniforms into handmade paper since 2007.” Donovan, Kyrie, Tool, and Albrecht have all been artists in residence at Oregon’s LH Project. In addition to collaborating with CP, Hughes, an Iraq War vet, also works with both Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) and print cooperative Justseeds. In 2014, Justseeds made a portfolio of prints called “Celebrate People’s History” to mark the IVAW’s “Ten Years of Fighting for Peace and Justice,” which includes prints by Hughes and Pinto.

Running wide and deep, the networks these connections represent suggest not only the degree of isolation that veterans experience in civilian life, but also the enduring power of both military training and what Marine Corps veteran, artist, and micro-biologist Thomas Dang has described as “a compelling camaraderie ignited between… combat veterans.”

At the heart of the transitioning veteran’s difficulties is a truth that everyone who has been through basic training knows: It is the business of the Army (or any branch of service) to “break you down so we can build you up.” And the military goes about that business very well: it breaks down a civilian so it can build up a warrior. In basic training, when a soldier is “out of line” (literally), the drill sergeant screams in his face, “What do you think you are -- an individual?”

The reassertion of an individual spirit is crucial to the warrior coming home, but how can a veteran break down the warrior so that an individual civilian may emerge? Art helps for many. Not only because it can be a tool of self-expression and self-discovery, but also because it provides a conduit by which to share with other veterans and with civilians. As Dang remarked in a recent interview, “Coming back from any deployment you get that feeling of isolation… creating art is a great way to express experiences… the community may not be able to understand in words.”

The humble cup is the chosen conduit of Berkley-based ceramic artist and 1991 Gulf War veteran Ehren Tool. “After my experience in the Marine Corps,” Tool states, “I am wary of the gap between the stated goal and the outcome. I am comfortable with the statement, “I just make cups.”

Rather than selling his vessels, which are decorated with war-related imagery and text, Tool gives them away. With over 16,000 cups gifted to date, the artist believes that “the cup is the appropriate scale to talk about war.” “It is a small hand-to-hand gesture,” he explains. “Small scale is where I think there can be real communication. The best cups I have made are cups that became a touchstone for a vet or someone close to them to talk about unspeakable things.”

“When I did decide to separate from the Air Force and pursue an arts degree,” says artist and ‘Global War on Terror’ veteran Erica Slone in this video, “it felt a little selfish to me.” Her project “Visualizing the Experiences of War,” which saw artists interpret the personal stories of their veteran collaborators, was both “a means to better integrate myself” and “my way of still providing a service, being useful to my new community.”

As Dirty Canteen puts it: “We were soldiers and humanitarians and though we can no longer do so in uniform, we choose to continue this service to others by using the arts.” The desire to serve is a powerful driver for these veteran-artists.

Sitting cross-legged on a small Persian rug and serving the tea that he makes on a hotplate, Hughes seeks to afford participants in his “Tea” performance a “space to ask questions about one’s relationship to the world.” Tea, the artist writes, “is not only a favored drink but a shared moment that transcends cultural divides and systems of oppression.” Invoking ritual, civility, and intimacy to create a container for conversations about war, violence, and dehumanization, Hughes insists that his intent to transcend that which divides us is not “a clichéd utopian statement, but… a reminder of a shared humanity that is so often overlooked.”

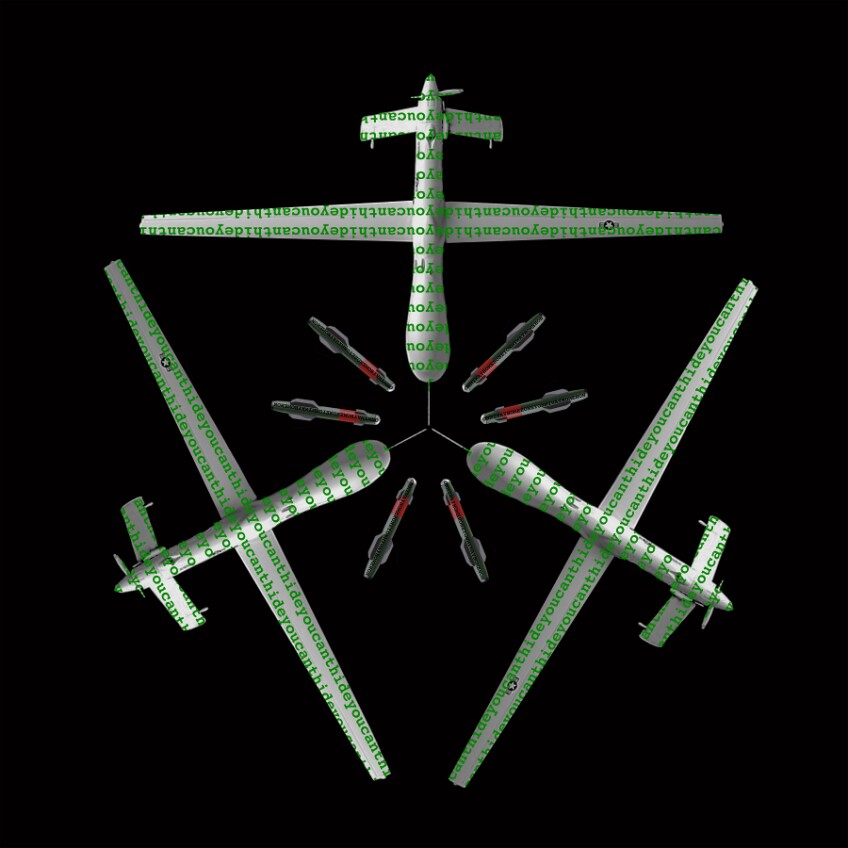

But what happens when the “war zone” extends to a computer terminal in a California office complex? With its repetition of the phrases “you can’t hide” and “on my way home honey,” Pinto’s “Death From Above,” a digital print of drones and bombs, invokes the confusion that such a circumstance may inflict on the moral foundation of a military operative. “I’m not satisfied with a 2-D print in a gallery... I want to do anything I can do," says Pinto, who has just co-authored a play with Emmy Award-winner Patricia Lee Stotter. Titled “American Sniper Redux: Behind the Flag,” the play picks up the eponymous movie on the day after sniper Chris Kyle’s funeral. “When veterans come back, there’s no ritual, no transition, we become society’s problem,” Pinto explains. “Society has to create that transition… [and] non-veterans need to understand their complicity in war.” “Redux” is a “dialog-starter for the conversation that America needs to have.”

In the 15th century, the French term avant-garde -- “advanced guard” -- named highly trained soldiers who went ahead of an advancing army and returned with information about the terrain ahead. In the 19th century, as the modern addiction to progress through innovation took hold, reformers adopted the term to describe people or ideas that spearhead change by challenging mainstream values. More recently -- anxious perhaps to signal their post-modern understanding of a contingent multiverse -- artists have approached the phrase “avant-garde” with trepidation. But when a generation of contemporary artists returns from war and insists, without irony, that a universal shared humanity is worth protecting, when they’re making “war-awareness art” and doing “anything I can” to challenge unthinking acceptance of global war, perhaps it is time to bring the term “avant-garde” back?