Rise of the Renter Nation: Solutions to the Housing Affordability Crisis

City Rising is a multimedia documentary program that traces gentrification and displacement through a lens of historical discriminatory laws and practices. Fearing the loss of their community’s soul, residents are gathering into a movement, not just in California, but across the nation as the rights to property, home, community and the city are taking center stage in a local and global debate. Learn more.

In 2014, the Right to the City Alliance released a new report, "The Rise of the Renter Nation."* The report was released at a time when experts were telling us the recession was over and the housing market was bouncing back. "Rise of the Renter Nation," on the other hand, made the case that the receding danger in the ownership market revealed a far deeper problem in the rental housing market. And as millions of Americans watched ownership slipped further out of reach, the numbers of permanent renters continued to swell.

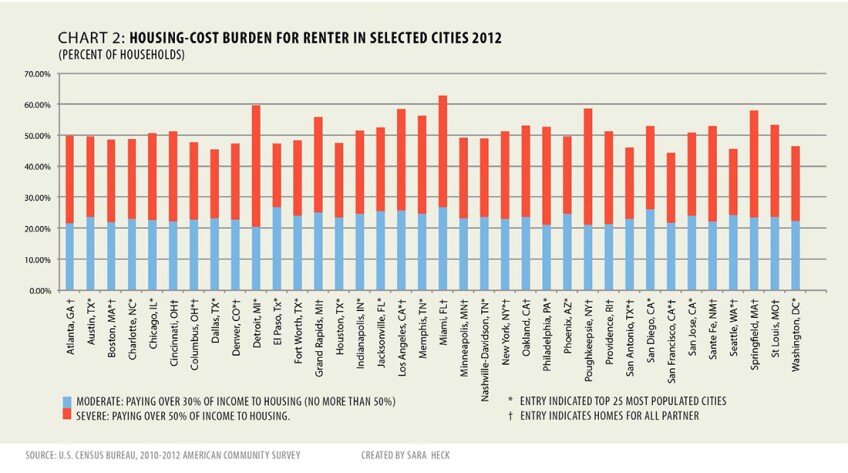

The report went on to argue that housing insecurity for renters was worsening, and would continue to do so for at least a generation, as the nature of housing in the United States overall undergoes a seismic shift. Most importantly, the report highlighted the disproportionate impact of the crisis on working class and low-income communities, people of color and women, even as the crisis creeps upward into the middle class. In the three years since the release of the report, its major arguments have been borne out. The crippling problem of ever-rising rents has reached the front page and become common knowledge, even as the problem continues to spread outward and largely unchecked, from the nation’s major urban centers.

The renter crisis has also brought increased attention to a major concern of the report: gentrification and the systemic displacement of individuals, families and entire neighborhoods in hot property markets. In more and more cities and urban regions around the country, the new gold rush for urban land has provided small time and corporate landlords with every reason to continuously raise rents and evict lower-income tenants at will. Combined with an economy that is increasingly dependent upon low-wage service work, the for-profit housing market is fueling a displacement epidemic that is now national in scope. Speculative investment in property has revealed the fundamental tension identified in the report between housing for profit and housing for human need.

The focus of the report on larger metro regions was balanced by the release in 2016 of Matthew Desmond prize-winning book, Evicted. Desmond’s research shed light on the role of evictions in creating and reproducing poverty in working class and low-income Black communities that are not facing the same displacement pressures observed in hot markets. His work shows us that displacement is not simply a consequence of speculative real estate investment and a booming regional economy; instead he highlights that many lower-income Americans, particularly low-income people of color, deal with chronic housing security on a daily basis regardless of where they live.

The rise of the renter nation is not an isolated phenomenon; it results from what the report calls a perfect storm of surging housing demand, a severe shortage of affordable rental units, declining or stagnant wages, and housing policy that favors higher income groups. Historically, it is one of many structural shifts that signal a final break with the prosperity of the post-WWII era that many took for granted as the normal state of affairs in the U.S. But, that economy and that world are gone. And if the kind of jobs (and wages) provided by companies like Uber represent the new economy, then the precarious world of renting represents the future of housing. Together these models of work and housing both reflect and drive the deep, long-term inequality that now defines the national landscape.

These changes reflect not only an economic downturn for many people but also a political reshuffle. The decline in union political power and its relationship to the rise of the low-wage service economy is well known. And, as the report highlights, we understand that the increase in the number and proportion of renters is related to this general economic decline. What we are only beginning to see is that this decline also represents the expansion of a politically marginalized class of people.

Renters have long been accorded a kind of second class status in the U.S. At the local level, in cities and towns across the country, homeowners are often the real power brokers when it comes to decision making at city hall, and they are accorded a status above that of a renter. Renters, when they are considered at all, are often treated as transient residents with no real investment in the community and therefore not deserving of a real voice.

This dynamic is especially powerful in smaller cities and suburbs of all size, where homeowners are often a majority. Cities with renter majorities and with relatively powerful renter constituencies, like San Francisco, are more exception than rule. And as renter populations continue to grow across the country, the challenge of effective representation at the local and regional levels is already being felt.

This status difference is not limited to the local level. Policy at the state and federal levels clearly favor existing homeowners in ways that produce very real benefits. In California, for example, Proposition 13, which limits property taxes, has for decades provided enormous subsidies to wealthier homeowners and shifted a disproportionate share of the cost of public services to lower-income households.

Similarly, the federal mortgage interest tax deduction reduces the tax burden on homeowners even as spending for the lowest income renters can barely cover one out of four people who qualify for assistance. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “More than four-fifths of the value of the mortgage interest and property tax deductions goes to households with incomes of more than $100,000, and more than two-fifths goes to families with incomes above $200,000.” The institutionalization of privilege for homeowners at every level constitutes a major challenge to confronting the housing crisis in any meaningful way.

The inherent unfairness of housing policy has contributed to the hoarding of wealth among the upper-middle classes and elite, and subsequently generated chronic instability for many others. Gentrification and displacement, once seen as limited to the most expensive neighborhoods and cities, have spread across the country as the proportion of renters grows in city after city. Land – real estate – has emerged a major source of super-profit for footloose global capital and the consequences at the individual, household and neighborhood level have often been devastating. In the Bay Area, for example, displacement pressures have torn apart long-standing communities, contributed to a public health crisis for lower-income residents and driven new forms of residential segregation.

Local governments, desperate for investment and finely attuned to the desire of established homeowners for ever-growing property values, have been unhelpful at best and hostile at worst. In many cases, they have actively blocked an adequate expansion of supply, particularly at levels that are affordable to the most impacted populations. At the same time, with a handful of exceptions, they have taken no real steps to protect existing renters from rampant speculation by wealthy and institutional investors, on the one hand, and smaller landlords seeking to cash out, on the other.

The structural nature of the displacement crisis is reflected in the extent to which it has generated consolidation within the rental market and a new class of landlord. Soon after Rise of the Renter Nation was released, Right to the City put out a companion report, the Rise of the Corporate Landlord. Again, the report was prescient and the entry of Wall Street into the rental market, led by firms like Blackstone, is now well-known.

Corporate landlords buy rental properties in volume because of the revenue rents provide but also to securitize the rents themselves and turn them into investment vehicles. And recently it was announced that Blackstone, through its subsidiary, Innovation Homes, would merge with Starwood Waypoint Homes in a $4.3 billion deal that would give the new goliath control over 82,000 homes in more than a dozen markets.

"Rise of the Renter Nation" maps the terrain of the crisis so as to provide a means to navigate and even reshape it. In response to an emerging structural housing insecurity for tens of millions of people, it offers the concept of housing security as a way to mobilize around, win and implement justice in the housing market. The concept is rooted in the experiences and reflections of an emerging housing justice movement, led by the most impacted communities, which has grown by leaps and bounds since 2014.

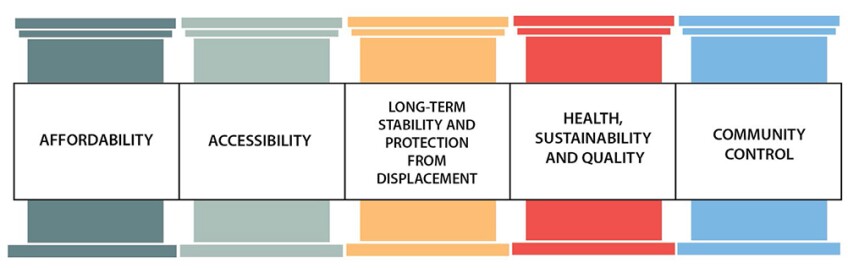

As the report states, housing security is both broad and deep. It is “not simply a reflection of affordability … instead it recognizes that decent housing involves simultaneous attention to a number of interrelated concerns that will provide a foundation for comprehensive policy reform." Specifically, the report offers five pillars that would constitute this foundation and serve as a lens through which to evaluate existing and new policy. In brief, these are: affordability, accessibility, protection from displacement, health and sustainability and community control.

The report concludes with existing and new policies that speak to each or all of these criteria, and that can be adopted at different levels of government. Some, like community land trusts, are gaining legitimacy even in mainstream policy circles, while others, like rent control, are progressing only through hard fought ground wars against an entrenched real estate aristocracy that is used to having its way in local politics. What they have in common is that they represent policies in which the right to a safe, decent home is held as a higher value than the profit a piece of land or a house can generate.

The political landscape has changed since the report in 2014. In California, a vibrant tenants’ movement has emerged, won some important local victories and is coordinating for bigger scale fights. Right to the City’s national Homes for All campaign has spread to new states and regions of the country and is beginning to challenge the state bans on rent control in places like Colorado, Washington and Oregon. The presidential election of 2016 has also shifted the terrain. Locally, many groups that are organizing around tenant rights have had to also turn to face the attack on immigrants and other communities. But these challenges have also opened up new possibilities and a new boldness to attack old problems. The housing justice movement, rooted in the most impacted communities, is well-positioned to play a leading role in a broader progressive revival.

*Disclosure: I am the lead author of the report.

Top Image: Renter's Day of Action in Boston, 2016. | Right to the City Alliance/Flickr/Creative Commons

If you liked this article, sign up to be informed of further City Rising content, which examines issues of gentrification and displacement across California.