New Tar Pits Discovery Reminds Us The Past Wasn't Entirely Different

You've almost certainly heard of the famous La Brea Tar Pits, those redundantly named fossil treasure troves in Hancock Park near the associated Page Museum. Oozing sticky tar to entomb hapless wildlife for at least 38,000 years, the tar pits have preserved a range of improbable former residents of the Los Angeles Basin ranging from sabretoothed cats to giant ground sloths to mammoths to leafcutter bees.

Wait, leafcutter bees? That's right: a paper published this week in the online scientific journal PLOS ONE describes a remarkable find of fossilized insects whose long-distant descendants may still be buzzing around your California garden.

It's a reminder that while present-day California is sadly deficient in cave bears, dire wolves, and many of the other animals that roamed its slopes during the Ice Ages, many of the Pleistocene California animals entombed in Wilshire asphaltum are still everyday sights around the Golden State.

In fact, it may surprise you that most of the fossils excavated from the tar pits belong to species that are still roaming the earth. Aside from a few of the very large mammals and one very large bird, the tar pits' bestiary would fit right in in the wild mountains north of Los Angeles: coyotes, bobcats, red-tailed hawks, and mule deer.

And some of the most useful fossils extracted from the pits are of much smaller living things: pollen, plant seeds, insects, and leaves, which can all reveal a great deal about what the Miracle Mile environment was like 25,000 years ago.

The recent bee find promises to be no exception. There are about 1,500 species of leafcutter bees in the world, with a few in California. One of them, Megachile gentilis, is a fuzzy white-and-black bee about half an inch long that inhabits woodlands and gardens in California and elsewhere. The bee is named for its females' habit of deftly snipping out semicircular swatches of leaf tissue from trees such as alder, cottonwood, and domestic fruit trees. They use the leaf samples to build "containers" for their eggs, which they place in subterranean nests, or occasionally in hollows beneath loose tree bark. The carefully gathered and crushed leaves create a nearly water-tight compartment in which the bee's larvae can develop and pupate. Gardeners in the know welcome the minor damage leafcutter bees cause their plants: most trees can handle the wear and tear, and the bees are important wild pollinators of a number of plants.

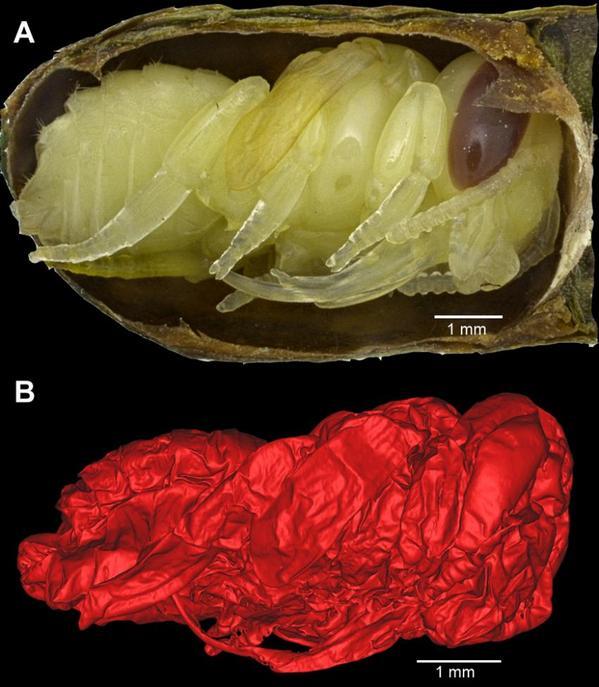

In 1970, a chunk of asphalt containing bee nest cells was excavated from Pit 91, and placed in the Page Museum's collection. After the sample had languished for some decades, a team of researchers from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Utah State University, and the UC Berkeley Museum of Paleontology subjected the nest cells to micro-CT scans to examine what was inside.

Given both the anatomy of the pupae and the construction of the nest cells, the team concluded that the species responsible for building the nest cells was probably Megachile gentilis.

The researchers also drew some conclusions about what the Hancock Park scene was like between 25,000 and 40,000 years ago, when asphalt seeped into the leafcutter bee nest burrow and entombed the insects. As the bees collect their leaf material from close at hand, the Rancho La Brea area was likely considerably moister than it is today, with riparian forests and perennial streams flowing nearby.

Some things change, and some things stay the same. It's tempting to think of fossil deposits like the tar pits as representing a wholly alien landscape, and it's true that mid-town would look very different with lions and camels snoozing under cottonwood and willow groves. But though California has lost quite a number of the species represented in the tar pits, most still carry on living in the state: the past has flowed more or less smoothly into the present. And Megachile gentilis still cuts Californian leaves, though it tends to be found in higher, cooler elevations than sea-level Los Angeles these days.

There's a whole lot more to learn from tar pits insects and other microfossils. "Because this is a fossil of rare life-stage, it's an exceptional find in itself," said lead author Anna R. Holden of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. "But it's just the tip of the iceberg, we know that insects offer a vivid portrait of the prehistoric conditions of this area, and there are literally thousands more to study."