From Downtown L.A. to Coachella: A Guide to the Physical Geography of Interstate 10

This may be the most unusual guide to Coachella. In fact, it's not necessarily about the festival or city, but rather a tour of physical geography that you pass through on your way from downtown Los Angeles along the 10 Freeway. So why not make the possibly traffic-jammed trip an opportunity to learn about Southern California in a way usually ignored? L.A.'s not a desert, but where exactly do you transition into it? Where's that 1.6-billion-year-old rock off the road? How about that still-living plant from 13,000 years ago? Which mountain range is among the fastest growing in the world? All that and more is below.

And please tell us what you think and how to improve this guide (and future ones). Comment below, tweet us at @KCET, or leave a comment on our Facebook wall. Author Chris Clarke can be found on Twitter at @canislatrans.

View LA to Coachella in a larger map

Table of Contents

From downtown L.A. to the Coachella Valley

- Los Angeles River: Exit 16, Santa Fe Avenue

- Boyle Heights: Exit 17, Boyle Avenue

- San Gabriel Valley: Exit 22, South Fremont Avenue

- Rio Hondo: Exit 27, Temple City Boulevard/Baldwin Avenue

- San Gabriel River: Exit 31, I-605 Interchange

- Mount Baldy: Exit 36, Azusa Avenue

- San Jose Hills: Exit 38A, Grand Avenue

- Pomona Valley: Between Exits 44 and 46

- San Antonio Creek: Exit 47, Indian Hill Boulevard

- Upland: Exit 51, Euclid Avenue

- Cucamonga Creek and Cajon Pass: Between Exits 54 & 55

- Jurupa Mountains: Exit 58, I-15 Interchange

- San Bernardino Mountains: Exit 64, Sierra Avenue

- Santa Ana River: Exit 71, Mount Vernon Avenue

- Crafton Hills and San Timoteo Badlands: Exit 81, Ford Street

- Yucaipa Valley: Exit 85, Oak Glen Road

- Transition to Desert: Exit 94, Beaumont Avenue

- Life Zones on Mount San Jacinto: Exit 98, Sunset Avenue

- Concrete Dinosaurs and Precambrian Rocks: Exit 106, Cabazon

- Whitewater River and the Salton Basin: Exit 114, Whitewater

- Little San Bernardino Mountains & Joshua Tree National Park: Exit 117, Route 62

- Santa Rosa Mountains & Indio Hills: Exit 131, Monterey Avenue

- Below Sea Level in the Salton Basin: Between Exits 131 and 142

Los Angeles River

Exit 16, Santa Fe Avenue

Just east of here the 10 crosses the Los Angeles River, then joins with I-5 and parallels the river for a few miles heading north. Now completely channelized in this stretch, the iconic Los Angeles River -- its concrete bed a preferred location for television car chase scenes -- runs 52 miles from its source in Canoga Park to its outflow east of Long Beach.

Once a perennial braided stream that provided abundant wildlife habitat along its floodplain, the Los Angeles River has been so thoroughly altered along its course that it has become symbolic of human degradation of the environment. Los Angeles began channelizing the river after the catastrophic Flood of 1938, and industrial development -- as well as runoff from a burgeoning city -- has caused serious damage to the ecosystem of the river.

Before channelization, the river's course was unpredictable; it often jumped its bed during floods, and its outflow moved back and forth along a stretch of coast from Long Beach to Santa Monica, depositing sediment and building soils across the L.A. Basin. Before a major flood in 1825, the river didn't even flow past this spot, but turned westward after emerging from the Glendale Narrows and meandered across the general vicinity of Koreatown until it met up with present-day Ballona Creek.

It's locked into its bed for now, but at some point the L.A. River will inevitably break out of its channel and choose its own path across the basin. If we still have a city here it'll be inconvenient, but it's what Southern California rivers do.

KCET's "Departures," a transmedia project about the shifting culture of Los Angeles, has covered the L.A. River extensively. Their project is a must-see.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Boyle Heights

Exit 17, Boyle Avenue

In a 1907 promotional book on Los Angeles written for the local Chamber of Commerce, Harry Ellington Brook described Boyle Heights as "a high, gravelly mesa or tableland." Fifty years before Brook's book, the local Californios knew this neighborhood as "Paredon Blanco," for the light-colored bluffs that stood east of the River. Behind both names is the sedimentary rock that underlies most of Boyle Heights, laid down as alluvial deposits during the Pleistocene epoch by the Ice-Age precursor to the Los Angeles River.

Beneath that Pleistocene rock lies an older geological formation deposited on the seabed during the Miocene around 15 million years ago. The "Puente Formation," named for the hills where it's the thickest, included a lot of deceased marine algae and other organisms. Over millions of years those organisms "fermented" into petroleum, and the Boyle Heights area was for some time a productive oilfield.

The fact that those older, lower layers were deposited on a seafloor and the younger ones were laid down above sea level might make you conjecture that the area had been lifted up out of the ocean in the intervening period, and you'd be right. The Pacific and North American tectonic plates have been moving against each other the whole time. The north end of the Peninsular Ranges have scraped westward across the south face of the Transverse Ranges (a group of east-west mountains that run between the Channel Islands and Joshua Tree National Park), squeezing the lands of the Los Angeles Basin up out of the sea. The proto-LA River laid down sediment washing off the San Gabriels and Santa Monica Mountains, and then -- as the land continued to rise -- carved away at them, creating this low range of hills 100 feet above the riverbed.

[Back to Table of Contents]

San Gabriel Valley

Exit 22, South Fremont Avenue

To the west is City Terrace, part of a low range of hills -- called the Repetto Hills by geologists and almost no one else -- that, with the neighboring Montebello Hills just east of here, stretch from the Verdugo Mountains and San Rafael Hills to the Puente Hills near Whittier. To the east lie the southern reaches of the San Gabriel Valley, with a 14-mile stretch of I-10 between us and the other end.

The hills here are thought to have been built by motion on the Elysian Park Fault, which runs from around Whittier Narrows up to Los Feliz or thereabouts. They're part of a geological formation -- the Elysian Park Anticline -- that also includes the hills in East Hollywood and the Macarthur Park escarpment.

These hills have been here for a long time. They were probably significantly higher before the San Gabriel Valley started to fill in with gravel and debris. Which took a lot of debris: The Valley covers about 200 square miles, bounded by the San Gabriels, the Puente hills, these hills and the San Jose Hills to the east. Think of this valley as a big bowl of gravel and you won't be far off; the valley is essentially a 200-square-mile catch-basin for debris washed off the fast-growing San Gabriels by the network of creeks that feed the San Gabriel River and the Rio Hondo.

The top of the Repetto Hills is where we cross between the LA River watershed and that of the Rio Hondo and San Gabriel rivers, though see the note at Exit 27 for an explanation of why things are more complicated than that makes it sound.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Rio Hondo

Exit 27, Temple City Boulevard/Baldwin Avenue

Immediately east of Temple City Boulevard, Interstate 10 crosses the engineered channel of Rio Hondo, a major tributary of the San Gabriel River. Or at least it was for 90 years, from 1867 through 1957. In 1957 the Whittier Narrows Dam was completed, which backs up both the Rio Hondo and San Gabriel, their waters mixing in the reservoir. Below the dam, an artificial alignment of the Rio Hondo carries some of that intermixed water into the Los Angeles River near the Imperial Boulevard Bridge.

What about before 1867? Before 1867, this was where the San Gabriel River flowed. A flood that year caused the San Gabriel to jump its banks and carve a new channel a few miles east. For a time, this channel was called the "Old River."

Rivers around here, left to their own devices, jump their banks pretty often. As a river carries sediment it drops some of that along its banks. Rivers that have been flowing in the same place for a while often flow significantly above the surrounding countryside; they've dropped enough sediment along their banks that they've raised themselves a few feet. When a flood comes those elevated banks give way, and the river carves a new channel. The process starts anew, and gradually the valley fills up with sediment. In the San Gabriel Valley, watercourses like the Rio Hondo have laid down sediment that's almost two miles thick in some places.

[Back to Table of Contents]

San Gabriel River

Exit 31, I-605 Interchange

We cross the San Gabriel River just west of the 605 interchange, only about 1,000 feet north of the point where Walnut Creek flows in from the east. The San Gabriel is a major Southern California river, running more than 60 miles from its "official" headwaters at the San Gabriel Reservoir to the Pacific Ocean at Seal Beach. If you add the forks above the reservoir high in the San Gabriels, the river's length gets even more impressive. The longest of them, the East Fork of the San Gabriel, rises in an alpine valley just three miles south of the ski resort town of Wrightwood.

The stretch of the San Gabriel we're crossing is a strange mix of natural and engineered river. A soil bed about 250 feet wide, complete with the occasional shrub or patch of grass, is flanked on either side by massive flood control berms. Every half mile or so the engineers have placed a baffle to break the flow of current, trap debris, and -- one presumes -- allow some water to percolate back into the aquifer.

Above the mountain dams, the San Gabriel's forks still hold native populations of steelhead, that endangered fish that perches uncomfortably on the boundary between "trout" and "salmon." Genetically, they're nearly the same as rainbow trout, and are classified in the same species. In terms of behavior (and flavor), though, steelhead resemble more closely salmon: aside from tasting more like coho than cutthroat, steelhead share salmon's habit of swimming out to sea when young, then finding their birth streams to spawn.

None of those steelhead up there can return to sea, and though in good flow years steelhead do try to come up the river from Seal Beach, none will make it past Whittier Narrows Dam: most will find their way blocked considerably before that. For now, this section of the San Gabriel River will remain devoid of its native steelhead.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Mount Baldy

Exit 36, Asuza Ave

In a heavily urbanized area like the San Gabriel Valley it can be hard to get a glimpse of what the place might once have looked like. Miles and miles of corporate office buildings, shopping malls and residences hard up against the freeway -- to say nothing of passing semis -- do not make for easy examination of the natural world.

But in this section of freeway through Covina, you can at least get a good long glimpse of the tallest peak in the San Gabriel Mountains. Mount San Antonio, popularly referred to as "Mount Baldy," rises to an elevation of 10,068 feet above sea level: a good 9,500 feet above our current elevation.

It's probably no accident that the tallest peak in the range -- and the highest point in Los Angeles County -- is at the east end of the range. According to geologists, the east end of the San Gabriel Mountains are rising faster than the west end, over toward the Antelope Valley. Rising at a rate of somewhere in the neighborhood of a millimeter a year, the San Gabriels are one of the fastest-rising mountain ranges in the world.

That doesn't mean the range is getting a millimeter taller each year. Erosion wears away at the range almost as fast as it grows. The line of checkdams and debris basins along the front of the range attests to that. Storms bring a huge amount of sediment down off the peaks -- especially now that fires have become more prevalent.

[Back to Table of Contents]

San Jose Hills

Exit 38A, Grand Avenue

This exit sits almost astride Walnut Creek -- a tributary of the San Gabriel -- and the fault named after it. To the west stretches the San Gabriel Valley, taking up 14 miles of I-10. Eastward, the freeway curves slowly to the right and gains altitude as it climbs the San Jose Hills, a low cluster of hills in the Transverse Ranges that separates the San Gabriel Valley from the Pomona Valley to the east.

With long, straight stretches of Interstate on either side of these hills, the mild turns in the road prove a bit of a relief to drivers. As an island of relatively undeveloped land in the midst of a sea of suburban sprawl, the San Jose Hills are a relief to non-human travelers as well. Keep a lookout for big birds flying overhead. These hills' coastal sage scrub habitat supports a range of animal life -- including red-tailed hawks.

This is a fine place for hiking, so if traffic is horrible and you desperately need to stretch you might consider giving up your place in line, getting off the 10 at Via Verde (Exit 40) and checking out the nearly 2,000-acre Frank G. Bonelli Regional Park just north of the 10 in San Dimas. This park offers trails, picnicking, swimming, and the world-famous water slide park name-checked in the film Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure (though fans may be disappointed to find that the film was actually shot in Phoenix, AZ, using a local water park as their location for the "Raging Waters" scenes).

The rocks of which these hills are made are sedimentaries and volcanics laid down during the Miocene epoch around 26 million years ago. This same series of rocks "crops out" in Topanga Canyon -- it's called the Topanga Formation -- in the Santa Monica Mountains.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Pomona Valley

Between Exits 44 and 46

Here at the west end of the Pomona Valley, the 10 follows the San Jose fault for a mile or so from Cal Poly to a spot between Indian Hill and Mills Aves, where the fault swings northward. San Jose Creek, a small channelized rill that drains the east edge of the hills, runs alongside the freeway for a half mile just at the hills' easternmost bluff. The creek then flows southwest between industrial warehouses and parking lots to join the San Gabriel in South El Monte near Pico Rivera Park.

Just a little way east is the topographical line that divides the massive, combined watershed of the San Gabriel/Rio Hondo/Los Angeles rivers from that of the Santa Ana River, Southern California's largest, as long as we exclude the Colorado River from consideration.

We're also at the western edge of the demographic region of California known as the Inland Empire, which includes the cities of San Bernardino and Riverside. About four-fifths of the residents of the Inland Empire live in the broad basin between here and Redlands, which has been somewhat arbitrarily divided into a number of sub-basins divided by very low rises. The one we're in here is called the Pomona Valley.

This stretch of the 10 is nearly as developed as the westward section in the San Gabriel Valley. Hints of the natural world here aren't easy to come by from the confines of a car. But if you were to get out and walk in some of the less-developed parts of the valley, you'd find the landscape a bit drier that it is to the west. In the hills here, chaparral starts to give way to sage scrub, and yuccas become more prevalent.

[Back to Table of Contents]

San Antonio Creek

Exit 47, Indian Hill Boulevard

Just east of this exit lies the line between Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties. 1,500 feet east of the county line, the 10 crosses San Antonio Creek, a major tributary of the Santa Ana River. This creek's headwaters are a half mile downhill from the summit of Mount San Antonio, which -- air quality and time of day allowing -- can be seen clearly in back of the V-shaped cleft in the mountains that is the San Antonio Creek's canyon.

Like many of the other streams we cross on this journey, this creek's upper reaches are wildly different from what we see here, with waterfalls as high as 50 feet. And like its cousins east and west along the San Gabriels, San Antonio Creek carries a huge amount of sediment during storms with a consequent history of dramatic flooding. The creek has built a broad alluvial fan at its mouth that slopes down into the valley, creating a minor rise from which the city of Upland takes its name.

These days, debris flows down San Antonio Creek are tightly regulated. The San Antonio Dam, completed in 1956, keeps debris from inundating the nonetheless poorly-sited San Antonio Heights neighborhood, and a set of "spreading grounds" diffuse the creek's floodwaters over a broad basin to soak into the earth and recharge the local aquifer. All dams are temporary, given a long enough timeframe, and the creek will eventually break free and resume building its alluvial fan.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Upland

Exit 51, Euclid Avenue

This spot, atop the broad San Antonio Creek alluvial fan, is as good a place as any to declare the boundary between the Pomona Valley to the west and the San Bernardino Valley to the east. Since it's part of that upland, highway engineers put the 10 in a trench through this section: it's going to be hard to see anything other than freeway for a couple of miles.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Cucamonga Creek and Cajon Pass

Between Exits 54, Vineyard Road & 55, Archibald Avenue

We cross Cucamonga Creek here, running in its channelized bed just east of a shopping center as the surrounding countryside, at least for now, begins to show some of the agricultural face that once characterized the whole valley. We cross the mighty Cucamonga just below its confluence with Deer Creek. Cucamonga Creek rises some 7,000 feet above you in a spectacular canyon in the eastern San Gabriels, one of the wildest places in the Inland Empire, with waterfalls and gorges and deep pools.

Thanks to the open fields around us and the Ontario Airport to our south, we've got a pretty good view -- especially of the western end of the San Bernardino Range to our east, hazily visible most days across the Santa Ana River basin. Due north of us, the San Gabriel Mountains seem to veer away from the road, fading a bit into the northeastern distance. That way lies Cajon Pass, the deep cleft between the San Gabriels and San Bernardinos. Only 3,775 feet at its highest point, Cajon Pass has been a favored route from the Mojave Desert to coastal Southern California for as long as people have been traveling in the area.

The pass also concentrates any wind blowing south out of the Mojave, and thus this stretch of the 10 often has some of the windiest conditions in Southern California. Electronic Caltrans warning signs along the route will alert you if winds are expected; take them seriously and slow down if it's gusting.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Jurupa Mountains

Exit 58, I-15 Interchange

If you were heading for Cajon Pass, this is where you'd get off the 10. The pass is a result of movement along the San Andreas Fault, which runs along the base of the San Bernardinos across the way and up into the cleft between the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains. A few miles east near Exit 61, Cherry Avenue, the 10 crosses an unnamed fault. To the southeast a low range of mountains is visible not far from the highway; they're the geologically complex Jurupa Mountains, which rise to 2,224 feet at their highest point, Mount Jurupa. A hiking trail leads to the summit.

The Jurupas made news in late 2009 when botanists announced they had found what may be the oldest living thing in California growing there: a clonal clump of a Palmer oak that they determined was in the neighborhood of 13,000 years old. The scrubby oak apparently sprouted from its acorn during what paleontologists call the Pluvial period, California's equivalent of the Ice Age. Conditions were significantly cooler and wetter in the Jurupas back then. Nowadays the ancient shrub's next of kin live only in the upper elevations of the tall mountain ranges that surround the Jurupas, as the lowlands have gotten too warm and dry for their liking. Somehow this one oak has held on since Paleolithic times.

Which is a much happier thing to think about than the other way the Jurupa Mountains have made the news: on the far side of the range an old quarry holds the notorious Stringfellow Acid Pits, which leak Superfund waste into the Santa Ana Watershed via Pyrite Creek, and which also contributed to the downfall of Reagan-era EPA administrator, Rita Lavelle.

[Back to Table of Contents]

San Bernardino Mountains

Exit 64, Sierra Avenue

To our east, the front of the San Bernardino Mountains is in full view, having been scraped up into the sky by movement of the San Andreas Fault which runs along the base of the range. The San Bernardinos' high point, Mount San Gorgonio, is the highest point in Southern California at 11,489 feet above sea level. It's the high point on the right end of the range from this vantage point.

Like the San Gabriels, the San Bernardino mountains are bordered on the north by Mojave Desert and on the south by more or less coastal-influenced valleys. Unlike the San Gabriels, however, the San Bernardinos also abut the Low Desert province in the western Coachella Valley. That and their greater size and height have contributed to these mountains being among the most biologically diverse in the state. The range hosts the critically endangered Mountain yellow-legged frog, the California spotted owl (and seven other owl species to boot,) and the San Bernardino flying squirrel, which is found only in these mountains and nowhere else.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Santa Ana River

Exit 71, Mount Vernon Avenue

Just east of here the 10 crosses the Santa Ana River, the largest river in Southern California (again, excepting the Colorado). Flowing from its headwaters on the north slopes of San Gorgonio Mountain, it gathers tributaries draining the San Gabriels and, in very rainy years, from the San Jacinto Mountains as well. It flows past Riverside, through a cleft in the Santa Ana Mountains from Corona to Anaheim and then out to sea at Huntington Beach.

Or at least it flows out to sea in theory. Most years, only a trickle reaches the estuary: most of the river's flow is fanned out into spreading grounds where it sinks into the ground, recharging the aquifer of northern Orange County.

Along with the Jurupa Mountains just to our west, the un-tamed sections of the Santa Ana River and its major tributary, Lytle Creek, provide some of the last remaining habitat in this valley for the California gnatcatcher, a tiny bird listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Most of the bird's preferred sage scrub habitat has been plowed under for agriculture and urban development; though it once ranged along the coastal half of Southern California from Ventura to the tip of Baja, it is now found only in a handful of locations that have remained undeveloped. As much as 90 percent of the gnatcatcher's historic habitat in Southern California has been destroyed.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Crafton Hills and San Timoteo Badlands

Exit 81, Ford Street

Eastward, the 10 begins its long climb toward San Gorgonio Pass. North of the freeway, the rugged Crafton Hills rise toward their high point at Zanja Peak at 3,546 feet above sea level. The Crafton Hills are essentially undeveloped, largely through the efforts of an active conservancy movement in the area. That's not to say that the hills are pristine: they were the site of the first rush of gold mining in California between 1820 and 1840 and evidence of other mining can be found there as well.

To the south of the freeway, the verdant and desolate San Timoteo Badlands remain probably forever undeveloped. Made up of of river deposits a few million years old or younger, the Badlands started eroding away after movement on the nearby San Jacinto Fault raised the area. The bedrock -- if you can call it that -- is so loose, and the slopes so steep, that nobody has figured out how to put a sturdy building foundation in the area. Most of the east end of the badlands is now protected as a nature preserve.

You won't see the most dramatic landscapes of the Badlands along the 10: those slopes are in the southern part of the hills, best viewable from State Route 60 east of Moreno Valley. But the badlands have offered some excitement here a bit closer to the 10. In 2010, workers building a Southern California Edison substation not far from Banning discovered what turned out to be a trove of 1,400 fossils from the early Pleistocene, including horses, giant sloths, and a cat larger than the sabertooths found at Rancho La Brea.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Yucaipa Valley

Exit 85, Oak Glen Road

This is the Yucaipa Valley, holding the cities of Yucaipa and Calimesa -- really more or less a single town that the county line splits down the middle. This valley, sitting between 2,400 and 3,000 feet in elevation, is considerably cooler in summer than the San Bernardino Valley, and is fairly well-watered given streams coming off the mountains. It was thus a favored place for the Serrano people: cool in summer, relatively warm in winter.

It's right about here that we find the easternmost stand of Coastal California-type habitat along the 10. From here eastward, as the road climbs toward San Gorgonio Pass, desert influences grow. The farther east you get from here for instance, the more likely you are to see Brittlebush growing as a roadside plant, its gray-green leaves sometimes confusing people who mistake it for coastal white sage. Along the same path, it suddenly gets much less likely that you'll see a coast live oak -- or any large native shade trees at all, for that matter.

Stand in Yucaipa or Calimesa and you can unambiguously say you're not in the desert. If you're heading east, by the time you get into Banning you're not going to be so sure about that.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Transition to Desert

Exit 94, Beaumont Avenue

We're at 2,600 feet above sea level here: the highest point in our journey along the 10 between Coachella and the L.A. River. This town's called Beaumont, from the french for "Beautiful Mountain," but we have more than one here to choose from. The road east from this spot runs through one of the deepest passes anywhere in the U.S.: a low pass with tall peaks on either side, each towering more than 9,000 feet above the road.

It's notably drier and dustier here than in Yucaipa, less than ten miles west. Desert species like chuparosa and creosote begin to appear at roadside. The farther east you go, the more deserty it gets. These massive mountains let only scant precipitation go past them from the Pacific. It's hard to decide where the desert truly begins along this stretch, but in Beaumont it has at least started to begin.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Life Zones on Mount San Jacinto

Exit 98, Sunset Avenue

From this vantage point, visibility allowing, the effect of altitude on environment can be clearly seen on Mount San Jacinto, southwest of us. At lower elevations, the mountain is basic brown: bare rock with dried grasses and occasional droughty shrubs the only accompaniment. Scan up the mountain face. At around 3,000 feet above sea level, a tinge of green begins to emerge: hard-leaved perennial shrubs that can take a bit of drought. Farther uphill they grow more thickly, and the green darkens. At just above 4,500 feet forest trees start to grow. From 5,000 to 6,000 feet they grow thickly -- at least in places where the ground's level enough to hold forests. The North Face mainly isn't level enough, but a few trees do cling to its precipitous slopes.

A hundred thirty years ago ecologist Clinton Hart Merriam pioneered the concept of "Life Zones," the notion that increased elevation brought ecological changes similar to those found when changing latitude. He came up with a whole system: lower desert slopes were called the "Lower Sonoran" zone, Upper slopes with Douglas firs and aspens were called the "Canadian" zone, etc. Merriam's system isn't used for much anymore; it's far too generalized. Each mountain really has its own zones. But his overall concept is still sound on San Jacinto: Climbing is like going north, as it lowers temperature and increases rainfall, and so climbing the 9,000 feet to the summit here is a bit like driving to central Oregon from here.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Concrete Dinosaurs and Precambrian Rocks

Exit 106, Cabazon

Sharp-eyed travelers will note what might be a familiar landmark on the north side of the highway here: a pair of concrete dinosaurs, staring off into the desert. There's an Apatosaurus and a T. rex, completed in 1975 and 1981, respectively. They're probably best known for their cameo in the 1985 film Pee Wee's Big Adventure, though they have showed up in other important works as well.

The creator and original owner of the dinos died in the 1980s, and his art has since been acquired by a religious group of young earth creationists. Inside the belly of the Apatosaurus is a gift shop with creationist tracts and exhibits. The owners are developing the property to include a creationist museum, in which kids will be taught that dinosaurs were created along with Adam and Eve 6,000 years ago.

Cabazon is nearly due south of San Gorgonio Mountain. On the north slopes of that mountain is a rock called the Baldwin Gneiss. Geologists estimate the age of that rock at about 1.6 billion years. That's 23 times longer than dinosaurs have been extinct. The gneiss was formed a billion years before there were fish, 900 million years before the earliest known animals of any kind. It's thus about 2.7 million times older than the age the creationists claim for the earth, and its people and dinosaurs.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Whitewater River and the Salton Basin

Exit 114, Whitewater

We cross the Whitewater River here, unusual among the watercourses on this stretch of the 10 in that it's usually full of briskly flowing water. The river flows off the east slopes of San Gorgonio Mountain and through a desert canyon full of sagebrush and bighorn sheep. After crossing under the freeway here, it flows out into the northwestern Coachella Valley, theoretically reaching the Salton Sea. In reality, most of its water gets used by Coachella Valley cities, or stored in the local aquifer.

The Salton Basin, which includes the Coachella and Imperial Valleys and the Salton Sea, is an "endorheic basin": water that flows into it never reaches the ocean. The basin is structurally part of the Sea of Cortez watershed; it's the result of the same tectonic forces that split Baja California away from the mainland like a sliver being chiseled off a piece of wood. But as the Colorado River was carving the Grand Canyon, it dumped the sediment down around where Mexicali is, building about a 30-foot high earthen dam across the basin. If it wasn't for that berm, some of the land you see to your east would be under the bright blue waters of the Sea of Cortez.

This is the downwind end of the San Gorgonio Pass, and hundreds of gigantic turbines stand between here and Thousand Palms to our east. More are installed each year.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Little San Bernardino Mountains and Joshua Tree National Park

Exit 117, Route 62 Interchange

To our north is the eastern end of the San Bernardino Mountains. They would fade almost imperceptibly into their sibling range, the Little San Bernardinos, if not for the deep Morongo Canyon just north of here, and the Morongo Valley to which it leads. This end of the San Bernardinos is indisputably a desert range: mojave yuccas, barrel cacti, and -- in the upper elevations -- Joshua trees have taken the place of the oaks and manzanitas found farther west.

The slope to our east was once an impressive forest of desert plants, mature barrel cacti and hardy yuccas enjoying the slight moisture through the pass. When Los Angeles was a young city and a southwestern influence in gardening became chic, Angelenos would come out here, find a likely-looking cactus, dig it up and take it home. Most of the mature specimens died soon after, but that didn't stop the collectors. Within a generation this slope was almost denuded of its formerly awe-inspiring vegetation.

South Pasadena socialite Minerva Hamilton Hoyt loved this part of the desert, and the destruction she saw here and elsewhere nearby made her determined to prevent the like from happening in the future. Hoyt was a tireless campaigner, and it was largely through her efforts that in 1936 Franklin Delano Roosevelt established Joshua Tree National Monument in the Little San Bernardino Mountains. Expanded significantly over the years and made a National Park in 1994, the park occupies the entire ridge line from here eastward to the horizon, and beyond.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Santa Rosa Mountains and Indio Hills

Exit 131, Monterey Avenue

To our south the Santa Rosa Mountains, a small part of the Peninsular Ranges, provide a backdrop to the swelling cities of the Coachella Valley. Home to endangered Peninsular bighorn sheep and a wealth of desert biodiversity, the Santa Rosas remain largely undeveloped -- though there are conflicts between urban use and wildlife preservation along the base of the range in the Coachella Valley.

The Santa Rosas are part of the Colorado Desert -- California's section of the larger Sonoran Desert -- and host desert plants typical of the region, the dramatic ocotillo being a prime example. On the far side of the range lies Anza Borrego Desert State Park, California's largest. On this side, the Santa Rosas are incised with abundant canyons, locally called "coves." Spring-fed creeks in these coves once supported Cahuilla Indian settlements; they now constitute prime residential real estate.

On the north side of the freeway sit the Indio Hills, tall enough in places to block the view of the Little San Bernardinos behind them. These hills sit astride the San Andreas Fault, one of California's largest geographic features, which stretches from the Salton Sea to the seafloor off Humboldt County. In the Indio Hills the fault provides a weak spot in the bedrock where groundwater can percolate to the surface. The resulting springs and seeps support thriving populations of native fan palms, from which a few local cities derive their names.

[Back to Table of Contents]

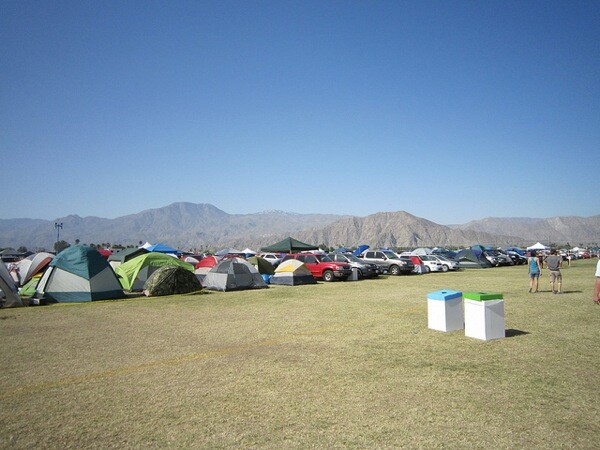

Below Sea Level in the Salton Basin

Between Exits 139, Jefferson Street and 142, Monroe Street

These are the exits recommended by Coachella's promoters for getting between the festival grounds and the 10. Between the two the freeway runs along the north bank of the Whitewater River, now dry as the proverbial bone. Even without water, the river provides important habitat for local wildlife. The wind-driven sand in and around the river bed is preferred habitat for animals like the Coachella fringe-toed lizard, now listed as endangered due to development of sandy places like this throughout the valley.

The 10 dips below sea level at Monroe Street and stays there for about five miles heading east, coming back up into positive elevation numbers at a point just west of the Coachella Canal. The Coachella Valley, the northern end of the Salton Trough, is what geologists call a graben: a valley formed when tectonic forces cause a piece of land to sink.

The Salton Trough is part of a larger rift valley, most of it filled with seawater. The combined action of the San Andreas Fault and the neighboring East Pacific Rise have peeled the Baja peninsula away from the mainland, a tectonic "wedge" with its point working away at San Gorgonio Pass. It may be a hundred years or a million before the Sea of Cortez penetrates this far inland, but it will, inevitably.

[Back to Table of Contents]

Please tell us what you think and how to improve this guide (and future ones). Comment below, tweet us at @KCET, or leave a comment on our Facebook wall. Author Chris Clarke can be found on Twitter at @canislatrans.