Are We There Yet? The Many Attempts and Failures to Fix the Bay Delta

An explanatory series focusing on one of the most complex issues facing California: water sharing. And at its core is the Sacramento-San Joaquin Bay Delta. Stay with kcet.org/baydelta for all the project's stories.

Every governor since statehood has, to some degree, presided over projects that damaged the Sacramento-San Joaquin Bay Delta. Consequently, every governor since Ronald Reagan has tried to fix the largest estuary on the West Coast. Among the modern challenges, encroaching salt must be kept out of the water distribution "hub" supplying cities and farms from the Bay Area to San Diego. Rising seas must be held back from subsiding land. The inflow of fresh water is low while demand for exports has steadily risen. Irrigation drainage, urban run-off, and ship traffic are feeding yet more salt, pesticides and grime into the system. What native fish are left are swimming toward extinction. Last but not least, all it would take is a Napa-sized earthquake to trigger collapse of an aging levee system and wash away one of California's oldest farming communities while cutting 25 million Californians off from critical portions of their water supply.

By way of fixing the Delta, Californians have passed laws, built dams, criss-crossed the state with aqueducts, and are now weighing up a multi-billion dollar pair of tunnels to carry fresh Sacramento River water under the estuary to export pumps. Act after act has been passed by the legislature and U.S. Congress to improve, protect, and even "reform" the Delta. There have been Delta accords, Delta task forces, Delta commissions, Delta councils. There have been so many analyses, there is an entire school of reports dedicated to studying the adequacy of the previous reports.

The opportunity to fix the Delta has been passed from governor to governor because every governor to try has failed. This is Governor Brown's fourth term at failing. Yet, if you look at the accumulated failures over time, there is good news. He's failing better. In fact, he's doing the best job failing since the projects were built. This qualifies as good news because failing worse could mean catastrophe.

* * *

We fail, in part, because no one can agree on what a fix looks like. "No matter what you do with the Delta, somebody's going to be unhappy," says Jay Lund, Director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at UC Davis. "If somebody's unhappy enough, it fails. Every Delta process eventually fails. It's a matter of what good things happen in the course of that process that wouldn't have happened otherwise."

If it sounds odd that one party could have so much power, meet just a few members of the circular firing squad who make up Delta interests. In the West Delta, where the freshwater estuary meets the saline San Francisco Bay, calls by cities dependent on Delta water for a barrier to block sea water incursions were defeated for lack of funds and debate with east Delta ports such as Stockton and Sacramento over what a blockade would do to shipping. The Delta's lowland farmers worried that a wall to keep the ocean out might keep floods in. Meanwhile, diversions by upstream Sacramento River rice farmers so weakened the downstream flows that once reliably repelled ocean influences that, by 1920, the West Delta town Antioch was suingupstream irrigators. By 1924, a saltwater worm had infested wooden piers of the Associated Oil Company near the strait connecting the Delta to the San Francisco Bay. Before the pilings could be replaced a pier collapse sparked a conflagration that left an oil tanker with six dead crew aboard drifting aflame in the Delta's most famous freshwater marsh.

Ironically enough, the dams and aqueducts built by water exporters and now blamed for breaking the place were unveiled in their days not just as fixes, but the fix of fixes. As approved by legislatures in 1933 and 1959, reservoirs created high in the Sierra on the Delta's main tributaries would provide flood control for Sacramento and the lowland farms. Regulated dam releases would supply the Bay Area, keep shipping channels at navigable depths, prolong growing seasons for Delta farmers, prevent salt intrusion from the San Francisco Bay, and generate hydroelectricity.

Those promises were kept, but not according to plan. A meticulous 1977 University of California report recounts how, after selling Deltans on the benefits of dams in 1933, California couldn't raise the money to build them and tossed the first wave of construction to the federal Bureau of Reclamation. It took decades for anyone to notice that salinity control fell out of the fine print of the Congressional authorization for the federal Central Valley Project. Only in the 1960s, when a by then rabidly jealous California subsequently built its own parallel export system, the State Water Project, did Deltans nail down salinity standards in the law.

When it came to the start-up of the State Water Project, as delicious as newspaper accounts were about how it was Miss Oroville on the podium with former Governor Earl Warren and then-Governor Ronald Reagan to dedicate Oroville Dam, and not the father of the project, former governor Pat Brown (Brown was offended that he was not invited to speak), the action that most mattered happened earlier and elsewhere. In 1967, the state water rights board published an estimated annual safe yield for both federal and state project pumps in the South Delta that amounted to enough water to submerge the entire state of Maryland under a foot of water. But it tucked in a proviso. It would, the board said, revisit the allocation pending results of water quality monitoring in the Delta.

No sooner had the water rights board made the allocation than the board was merged with the overseers of water quality. Under the newly created regulator, the privilege to export clean water was hinged on the duty to leave clean water behind.

And then, buried in the fine print of the 1967 water rights decision, there was what water managers argue is the single greatest oversight of California's aqueduct system. As the permit noted, details for a cross-Delta canal to "transport water from the Sacramento River in the vicinity of Hood to the intakes of the California Aqueduct ... have not been finally determined."

The reason this cross-Delta conduit was needed, even presumed, is that that export pumps were built in the south Delta, a place that in water quality terms amounts to a bad part of town. Thanks to a Reclamation dam near Fresno, inflow from the nearest of the namesake tributaries to the south Delta, the San Joaquin River, has been reduced to little more than salty field drainage. Only buttloads -- many, many buttloads -- of far fresher water released by project dams into the Delta's northerly tributary, the Sacramento River, would keep the south Delta swamp blend up to regulatory muster. Building a canal that would divert Sacramento River good stuff before it entered the swamp, many Northern Californians believed, amounted to a water grab that would leave their local supplies as polluted as the San Joaquin's farm dregs.

* * *

In 1971, Delta water hadn't even reached Southern California before court battles began over the standards for the projects issued by the newly empowered State Water Resources Control Board. Faster than you can say "Ronald Reagan," the board's the first decision affirming the environment and threatening exports was stayed by a judge.

A brace of critical drought years set the backdrop in Jerry Brown's first term as the water board reconvened. Next to freshwater exports, nothing concentrates salt in the Delta like drought. When in 1978 the Board again came back with standards sure to slash exports, the very agency that California had begged in the 1930s to come fix the Delta called its lawyers. The State Water Resources Control Board had no jurisdiction over their federal operation, argued Reclamation. They were formed to impound and export water for agriculture and Bay Area cities, and that they were doing.

Enough reservoir-filling snow fell in the Sierra during Brown's second term to avert full scale crisis, however by 1981 drought was back. As the legislature approved the still-not-built cross-Delta aqueduct, exports from the south Delta state and federal project pumps reached a then all time high of 4.85 million acre feet. The loss of enough water to cover the land mass of roughly New Jersey a foot deep in water was all Northern California needed to lead a veto of the Peripheral Canal. The gist of the message from the Deltans to exporters? Forget your canal. We drink swamp blend, you drink swamp blend.

* * *

As Brown's second term ended in 1983, failure -- failure to build the Peripheral Canal, failure to enforce water quality standards, failure to protect fish, failure to restore wetlands, failure to deal with the threat of levee breach -- was less of an embarrassment for a governor than the way California managed its water. Two terms later, Brown's successor George Deukmejian had failed to build slimmed-down versions of the Peripheral Canal. Twice. Reclamation's lawsuit against the State Water Resources Control Board failed. The board failed too. The same appellate court decision that smacked the federal project dismissed the state board's 1978 standards as irrational and unfair.

As the browbeaten board re-re-re-convened in 1988, again the background was drought, but this time it wasn't during a critically dry year or two. It was six years of excruciating drought. After provisional standards published late in 1988 again spelled export cuts, Governor George Deukmejian made the water board chair an offer he couldn't refuse: Revisit the board's finding or be fired.

"There is some justifiable criticism that we haven't gotten all the input that we should," the chair mumbled to reporters early in 1989 as he resumed what in that session alone had already been six months of hearings that created more than 40,000 pages of testimony. That year south Delta pumps exported enough water to submerge the state of Massachusetts a foot deep, and Sacramento River winter-run Chinook salmon landed on both state and federal endangered species lists.

Pete Wilson succeeded Deukmejian as governor under such persistently blue skies that a 1991 profile by LA Times columnist George Skelton caught the new governor staring out his office window and muttering, "It's a beautiful day, dammit." As the board again attempted to curb exports, Wilson's solution was blunt. He disbanded the board. "I have the authority," he told reporters as he folded the state's water quality regulators into his personal "drought task force."

There was no such rabbit to pull from a hat when in 1992, a Delta-area House Representative named George Miller got an act passed by U.S. Congress requiring Reclamation to release 800,000 acre feet a year for fish and wildlife. Not that, as a report later showed, Reclamation eventually coughed up that much. However, that critical year of 1992, having a third of the federal project's south Delta draw reapportioned to fish set off repeal efforts to embarrass the enemies of Obamacare. The state's water utilities were soon staring at credit downgrades while a once common native fish, the Delta smelt, was listed on federal and state endangered species lists.

Cue the celestial choir to herald two heaven-sent events. First, it started to rain. Second, Wilson, and federal authorities so fed up with him that they were about to do the water board's job for it, had an idea. Why let a good crisis go to waste? It was the era of "New Democrats," "third way" politics, and "governing by consensus." The circular firing squad could hug it out! The Bay Delta Accord was signed launching a state-federal workshop-athon called CalFed. CalFed even had a slogan: "Getting better together."

Out from under drought's hammer, for the next five years, the Delta's opposing parties and roughly two dozen state and federal agencies workshopped. They thought about what they wanted, listed what they wanted and, in 2000, unveiled a 30-year-plan for the Delta giving them what they wanted. Their wish list included: restored wetlands, recharged aquifers, healthy native fisheries, new dams and more storage, initial work on canals that could become a peripheral canal.

Nowhere in the CalFed record of decision, however, was there an option for reducing Delta water exports. As for a growing number of endangered native fish, extra water would become available in part through an "environmental water account" in which federal and state exporters could export surplus water when fish were least at risk from pumps and stop pumping when they most imperiled.

It took eight years for a suit by Delta area counties that claimed CalFed's failure to entertain export cuts violated environmental review laws to fail in the Supreme Court. The court maintained that, since reducing exports wasn't a goal of CalFed, it was not a failure that they had failed to analyze it as an option. As for extra water for fish from the environmental water account, Contra Costa Times reporter Mike Taugher in 2009 discovered that $200 million of this went into the pockets of Central Valley farmers -- 20 percent of it to billionaire Paramount Farms owner Stewart Resnick.

* * *

CalFed was a $4 billion zombie project on its way to excoriation by the Legislative Analyst's Office and Little Hoover Commission when, one sunny June morning in 2004, a Delta fisherman noticed a 300-foot breach in a privately-owned levee at Upper Jones Tract. The breach, ten stream-miles from the south Delta export pumps, was in a 12,000-acre man-made island whose fields sat between ten and fifteen feet below sea level.

Three days into the breach, roughly a third of all the water then in the Delta east of Suisun Bay was sucked into tract's diked fields. Key points of the failure were later enumerated by the Public Policy Institute of California: the levee had been inspected for the local reclamation district only day earlier; the flood coursed directly toward the pipeline carrying the water supply for the cities of Oakland and Berkeley; the U.S. Army Corps initially refused to aid rescue efforts because it wasn't a "project" levee; the railway company that could have stopped the flood from inundating half the island refused to act; as the Army Corps finally scrambled to reinforce a levee to save Highway 4, the city of Stockton sold it channel dredge material contaminated with toxic metals that it was supposed to destroy to use as fill abutting the public water supply; and local farmers blamed a beaver den and even their exterminator, not age and maintenance of the levees, for the failure. The cost of levee repair alone reached $90 million.

If there was good news, it was that California had just elected a governor who knew how to read a disaster script. Ignoring party politics, the Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger appointed a seasoned Democrat to run the State Water Project. Even bipartisanship, however, can't make it rain. By 2007, drought was back and so badly that, for the first time in project history, a Central Valley judge shut down South Delta pumps because they were ravaging the once common, by then protected, native fish, the Delta Smelt.

Schwarzenegger had another ace up his sleeve. He'd already deputized a slightly built and intensely bookish lawyer fond of intimidating the unwary with chapter and verse of California water law. The governor waited as former mayor of Sacramento and state assemblyman Phil Isenberg extracted what passed as a set of workable set of compromises from the circular firing squad. By 2009, Schwarzenegger wouldn't let the legislature out of session until the bones of the Isenberg group recommendations were folded into what became the 2009 Delta Reform Act.

* * *

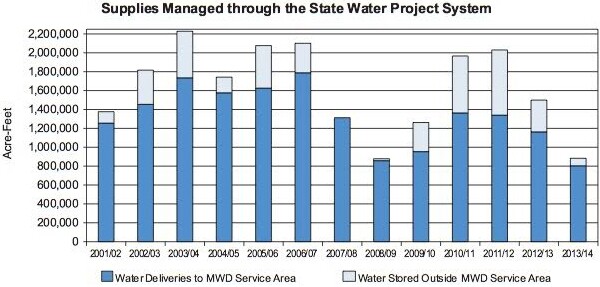

As Brown returned to the governor's office in 2011, the Delta Reform Act had already made clear that it wasn't a question of would exporters face cuts, but how deep the cuts would be, particularly in drought years. The pill that no export customer other than the rich Metropolitan Water District of Southern California seems quite ready to swallow is getting less for more and paying billions of dollars for the tunnels.

Ironically, because in many ways the fixes of fixes in 1933 and 1959 actually worked, the group most opposed to modernizing the projects with tunnels owe their continued existence to their rivals. Delta farmers only continue to grow asparagus ten feet below sea level because project infrastructure buffers them from drought and floods. During the Jones Tract disaster, state pumps stopped and federal ones slowed as dam keepers in the Sierra opened floodgates of Sacramento River dams to recharge the Delta's wetlands with fresh water.

Yet, as Deltans see it, the only insurance they have that their interests -- above all, refreshment of the south Delta's swamp blend with Sacramento River good stuff -- will continue to be protected are 24.5 million other Californians dependent on Delta exports. We drink swamp blend, you drink swamp blend.

That some of the water project customers most at risk aren't Southern Californians, who are buffered from utter disaster by a large network of storage reservoirs, but Bay Area residents living near the Delta is "news to most people," says UC Davis's Jay Lund. It wasn't, however, news to the former mayor of Oakland, Jerry Brown, when he began his third term as governor 2011.

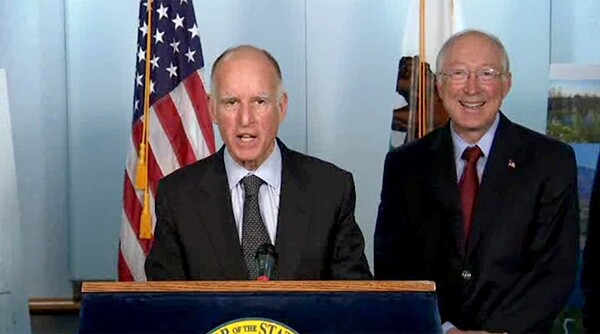

The following year, Brown stepped before news crews to unveil plans for a twin tunnel version of the Peripheral Canal. As presented, it would go underground to avoid existing surface land uses. It would take less water than previous canal designs and Delta stakeholders would be included in operational decisions. Standing next to him were federal and state wildlife officials now arguing that the best chance they have to protect remaining native fish is to alternate water withdrawals from the Delta from the north and south during migration. "Analysis paralysis is not why I came back," said Brown. "We have farmers, we have fish, we have environmentalists, we have citizens, and we have to make this work." As Brown added, "I want to get shit done," Interior Secretary Ken Salazar collapsed into laughter behind him.

The difference between Brown in drought in his first two terms and Brown in drought now is that this drought is worse and Brown is better. South Delta exports have dropped more precipitously than any time in project history. Perennially rebellious Deltans are cooperating with water use reporting and conservation efforts from which previously they enjoyed historical immunity. Brown's appointee to head of the water board overseeing allocations and water quality is no flunkie but a former Western Director of the Natural Resources Defense Council. Oddest of all, the Governor of California is not afraid to tear up the kind of fix-the-Delta wish lists made under CalFed. When Delta restoration efforts proposed around construction tunnels proved unrealistic, earlier this year Brown went before cameras, revised the acreage down from 100,000 to 30,000 acres, and unapologetically insisted that it was good news because "it's real." An updated environmental impact report for entire project is due out soon.

Maintaining the swamp blend in what are now the driest three years on record for Delta tributaries has become so difficult that, in recent weeks, the Department of Water Resource dispatched rock-laden barges to the central Delta to create an emergency barrier to block saltwater incursions from the San Francisco Bay. The last governor to do this was also Jerry Brown in the critical drought years of 1976-77.

"He's unusual," says UC Davis's Jay Lund. "He knows a lot about this problem. Probably more than any politician around. He's an environmentalist governor, but he doesn't always sound like that."

Brown may or may not succeed in getting the tunnels built before an earthquake or levee failure turns the Delta into the new New Orleans. "This has defeated five governors in 40 years," he told an audience at the University of Southern California this week at an L.A. Times water talk broadcast by KCET. What is clear is that sharp reductions in exports are inevitable whether we prepare for them or not. Since projects began filling federal and state aqueducts with south Delta water in 1951, they have taken enough water to cover the states of California, Oregon, Washington a foot deep with enough left over to flood a place the size of West Virginia. Nothing about climate change suggests that a footprint that size is sustainable for the next sixty four years.

Yet the circular firing squad dependent on Delta water now comprises 25 million Californians. Because of this, says Lund, every governor involved in the transition will, to some degree or another, fail. "Eventually you're going to run foul of the politics," Lund says. "Enough stakeholders will find it politically convenient to assassinate the current process so some future process will be needed."