Biologist: Petition to Remove Protection From Bird Based On Questionable Science

A petition by two real estate developers' trade groups and the Pacific Legal Foundation to remove the coastal California gnatcatcher from protection under the Endangered Species Act is based on questionable science, according to an expert on bird genetics at Occidental College.

The petition to delist the coastal gnatcatcher, Polioptila californica californica, cites a 2013 paper in the journal The Auk that found no genetic basis for considering the birds a valid subspecies of the more common California gnatcatcher. And since the study shows there's no reason to consider the coastal population a subspecies, says the petition, the coastal California gnatcatcher doesn't merit the spot on the list of Threatened species the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service gave it in 1993.

But John McCormack, assistant professor of biology at Occidental and director of the school's Moore Laboratory of Zoology, said in a conversation with ReWild that the 2013 study of the genome of the coastal gnatcatchers failed to use the best available scientific methods to determine the validity of the coastal subspecies.

The Pacific Legal Foundation's petition to delist the gnatcatcher was filed in June on behalf of the National Association of Home Builders and the California Building Industry Association. The reason for the developers' interest in delisting the coastal California gnatcatcher is straightforward: the birds' Threatened status makes it somewhat harder to bulldoze intact sage scrub habitat to build yet more suburbs in Southern California.

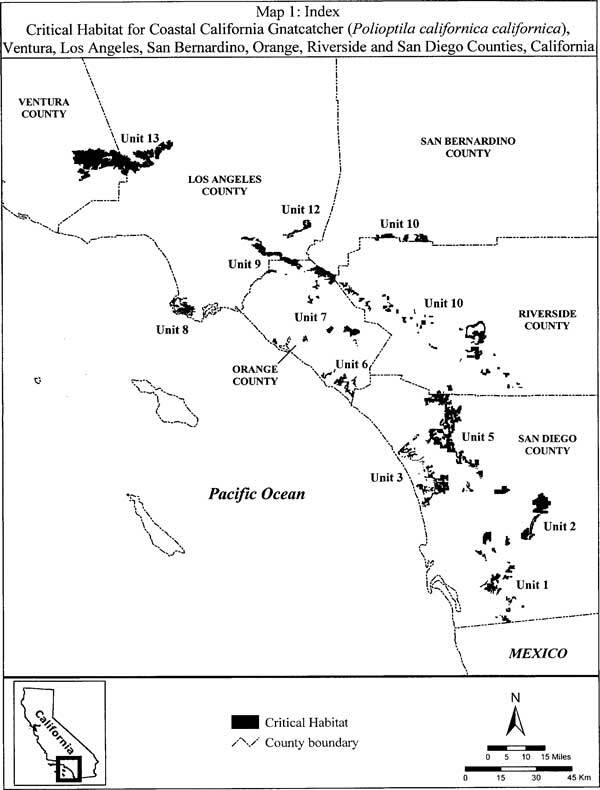

That's where an estimated maximum of 2,500 or so coastal California gnatcatchers still eke out a living, with 197,303 acres of designated Critical Habitat in Ventura, L.A., Orange, San Bernardino, Riverside, and San Diego counties.

The Pacific Legal Foundation's earlier petition to delist the subspecies in 2010 was based on arguments on a 2000 paper by Robert M. Zink, the lead author of the 2013 Auk paper. In that work, Zink et al found insufficient differences in the mitochondrial DNA of the coastal subspecies and other California gnatcatchers to justify calling the coastal population a subspecies.

But in 2011, USFWS declined to take the coastal California gnatcatcher off the Theatened list, saying that the mitochondrial DNA study wasn't persuasive. Mitochondrial DNA tends to evolve more slowly than DNA from other parts of the cell; a putative subspecies like the coastal gnatcatcher that has diverged from its parent species only relatively recently wouldn't have had time to accumulate enough differences in mitochondrial DNA to indicate evolutionary divergence.

USFWS said it couldn't delist the gnatcatcher subspecies without more compelling evidence that the coastal birds were not a valid subspecies, and mentioned DNA from cell nuclei -- nuclear DNA -- as a place to look. And so Zink et al's 2013 paper compared DNA from eight specific "loci" -- portions of the birds' nuclear genome -- and found insufficient evidence that the birds had the populations had evolved enough genetic distinctiveness to warrant a coastal subspecies.

The problem is, McCormack told ReWild last week, that those eight loci were again selected from portions of the nuclear genome that are relatively conservative in evolutionary terms: they don't accumulate changes through mutation or other means as rapidly as other parts of a bird's genome. And eight, to invert an old sitcom title, is by no means enough.

"We now have the technology to look at thousands of genetic markers across a bird's entire genome," said McCormack. "That includes portions of the genome that change more rapidly over time, so that we could have a far more accurate measure of the actual degree of divergence between the populations."

There are "microsatellites," for example; short repeated sequences of DNA that evolve changes rather quickly compared to other parts of the genome. Though birds seem to have fewer microsatellites than many other kinds of animals, comparing microsatellites found in different gnatcatcher populations could have given a more precise picture of the separation between those populations.

But microsatellites are usually found in what's called "non-coding DNA," or DNA that seems to have no obvious effect on the organisms whose genome contains it. In biologists' terms, microsatellites don't affect their owner's "phenotype": the actual physical makeup and genetically influenced behavior of the organism. And differences in phenotypes are really the core of the question whether coastal California gnatcatchers are a valid subspecies.

McCormack suggested that looking at so-called restriction site associated DNA markers, sections of DNA that geneticists use (to oversimplify immensely) to find differences in DNA sequences, would have given biologists a look at differences in the coastal and non-coastal gnatcatchers' genomes that actually had some effect on the birds' phenotypes.

And McCormack isn't kidding when he says that current technology allows comparing thousands of genetic markers get a clear picture of the genetic differences between groups of organisms. In 2013, McCormack was lead author on a paper published on the online peer-reviewed journal PLOS One describing the results of comparing 1,541 genetic loci among 33 species of bird.

So why study just eight loci from conservative sections of the gnatcatchers' nuclear DNA? McCormack is blunt. "Fish and Wildlife left a loophole big enough for a lawyer to walk through. The agency said 'We want nuclear DNA studies before we make a decision to delist the gnatcatcher.' Zink's study allowed the lawyers to check that box. 'See, we did nuclear DNA.'"

In a letter to the editor published on the Los Angeles Times' website last week, McCormack was equally blunt in his assessment of the Zink paper, which was delivered to him for review at a different journal. McCormack's review of the paper was not positive.

"[T]he study did not use modern methods," wrote McCormack, continuing:

In my review, I was critical of the genetic markers and environmental characteristics the authors chose to assess whether the gnatcatchers were different from other populations. Their choices made it a foregone conclusion that the authors would find no evidence for distinctiveness. Instead of addressing my criticism, they apparently chose to resubmit their study to another journal in hopes of finding more sympathetic reviewers.

Zink's study was funded in part by grants from real estate developers, though Zink -- a biologist at the University of Minnesota -- maintains that the funding had no effect whatsoever on the study's conclusions. On his webpage, Zink writes that he doubts whether any bird subspecies actually exist at all. Which certainly makes his participation in the gnatcatcher debate interesting.

Regardless of the degree to which Zink's funding and/or personal scientific convictions either did or did not color his research, USFWS is legally obliged to make its decisions about listing and delisting species or subspecies based on the best available science.

That's the precise legal language: "best available science." In McCormack's PLOS One article, he and his co-authors determined that they got significantly "better available science" about the evolutionary family tree of birds when comparing 1,541 genetic loci than they did when comparing only 416 loci.

Whether a study of just eight loci represents the "best available science" on the coastal California gnatcatcher is up to USFWS to decide.