Salton Sea Policy-Making Excludes Vulnerable Purépecha Community Members

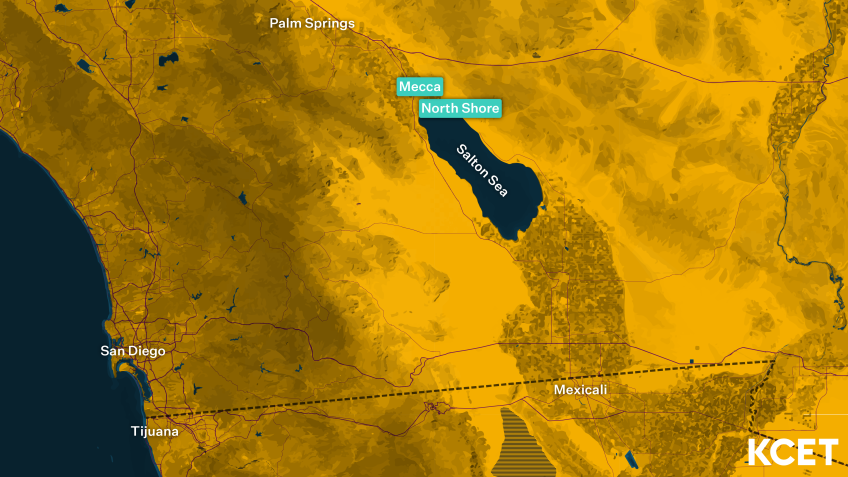

Meriguildo Ortiz migrated to the Eastern Coachella Valley from Michoacán, Mexico just over 30 years ago. Like the majority of Purépecha immigrants — indigenous to the southwestern region of Michoacán — he works in agricultural fields, picking citrus each day. Now, Ortiz lives in North Shore with his wife and four children, volunteering as a community leader to support approximately 30 Purépecha families in North Shore and 50 families in Mecca.

Residing less than a mile from the Salton Sea, Purépecha farmworkers like Ortiz stand on the frontlines of one of the greatest environmental and health justice crises in the state. As the Salton Sea continues to evaporate, local residents report increasingly common cases of asthma, nose bleeds and allergies. The state has proposed solutions, such as the 10-year Salton Sea Management Program, but Purépecha community members who speak neither English nor Spanish, face limited internet access and lack high levels of education can rarely participate in decision-making. Last October, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed AB 1657 into law to advance lithium development in the region, widening the gap between state economic priorities and Purépecha community interests even further.

A lot of the technical language that is being presented is non-existent in our language to begin with.Maximiliano Felipe Ochoa, California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA)

The Salton Sea formed in 1905, when a Colorado River dike broke and flooded an ancient riverbed where the Riverside and Imperial Valleys now stand. Over time, the Sea grew contaminated with pesticides and chemicals due to agricultural runoff and irrigation wastewater. In 2003, the Quantification Settlement Agreement diverted water from the Colorado River away from the Sea, so the Imperial Irrigation District and San Diego County Water Authority agreed to send fresh water in its place. This deal ended in 2018, and with an intensifying drought, the Sea has begun to rapidly evaporate and increase in salinity, polluting the air and killing off wildlife.

For farmworkers who spend long hours laboring outside, the health impacts associated with the Salton Sea are especially intense. Data on farmworker demographics in the Eastern Coachella Valley is hard to come by, but the majority are of Latinx descent and low-income status. Maximiliano Felipe Ochoa, a community worker for the California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA), estimates that six to ten thousand Purépecha people live in the region. Many are undocumented and lack access to medical care, traveling to Mexicali to seek higher quality doctors that don’t require Social Security numbers. Some also migrate seasonally and move up the coast following crop growth, limiting their housing options — often to trailer parks or with many families in a single home.

While Purépecha residents have received some information about their health risks, many are just beginning to understand why the Sea is drying up. Government agencies hold public informational meetings to gather feedback, but these are often during daytime work hours and dominated by jargon. Moreover, many community members lack the internet access to log onto a Zoom session.

Ochoa migrated to the Eastern Coachella Valley from Michoacán when he was eight years old. He began informally translating between Purépecha and English when he was in middle school, becoming a key resource for school administrators with no other way to communicate to students’ families. After community-based organizations pushed for agencies to expand language access, CalEnergy contracted Ochoa to translate resources about proposed lithium projects to Purépecha.

But translating written documents remains challenging because many community members cannot read or write in Purépecha, let alone understand the scientific complexity of lithium.

Ochoa has only done live translation once.

"A lot of the technical language that is being presented is non-existent in our language to begin with," he says.

Ochoa received a Master’s Degree in Public Policy from University of California, Irvine in 2018, which helped him understand the techniques proposed to extract lithium from the Salton Sea’s geothermal brines and create large batteries that power carbon-free cars. According to Ochoa, however, this concept is completely foreign to most Purépecha farmworkers, whose days include little space for environmental justice advocacy among the pressing priorities of finding work, keeping a roof over their heads and feeding their families.

While lawmakers claim that the lithium extraction would create hundreds to thousands of new jobsand bring rampant economic development to the region, Ochoa questions, "Development for whom specifically?" He says these jobs would likely require special STEM degrees or PhDs, even just for warehouse maintenance, and he doubts they will appear until ten or 20 years from now.

Meriguildo Ortiz hopes that the government could rehabilitate the Salton Sea to once again attract tourists who would buy Purépecha artisan crafts. Yet when asked for his perspective on lithium extraction, he had never heard of the plans. Ortiz has attended some public meetings related to the Sea, but he only has a very general understanding of the pollution.

"It would be extremely helpful if there were an interpreter," he said in Spanish.

To Ortiz, the youth generation represents the bridge to informing older community members. Young people who finish school and understand both English and Purépecha could more comprehensively explain the concepts that government officials try to relate in meetings. In these trusted spaces, older generations might feel comfortable asking questions and grow more equipped to provide well-rounded feedback.

According to Paulina Rojas, Program Manager at the Youth Leadership Institute’s Eastern Coachella Valley office, many youth grow up familiar with the Sea’s foul smell and dead fish floating near the shore. Yet the advocacy that reaches them often focuses on nature preservation.

"That can be very jarring for a young person who’s grown up in proximity to the Salton Sea, and then they never hear about their own communities in decision-making spaces," Rojas says.

If agencies held educational sessions about the Salton Sea during school hours, youth could easily bring that information home and even go door-to-door to share resources with neighbors, as many did during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Though the exception, a few Purépecha voices have consistently worked to center their community interests in advocacy spaces. Maria "Conchita" Pozar, a Community Researcher at the University of California, Riverside, has built recognition by frequently attending informational meetings about the Sea and gathering community members in her North Shore home.

While her research work has connected her to these informational spaces, she is also the daughter of migrant Purépecha farmworkers and the mother of two daughters who suffer the allergies that have grown so common. Despite her ongoing efforts, Pozar says her community almost never sees the results of studies that outside researchers conduct or public health responses that reflect her community’s needs.

"We’ve never had someone who’s said: this is what’s happening with the Sea, this is what we can do, this is the danger that you are in, and what research do you want to be developed? There is no direction to go in and that is the most concerning thing," Pozar said in Spanish.

As many Purépecha community members rely on local radio stations while working, Pozar suggests advertising public meetings on the radio, creating informational segments with updates on the Salton Sea and holding meetings with accurate interpretation after daytime work hours.

"These are the steps that they would have to take to gather our opinions," Pozar said in Spanish.