Honoring A Water Warrior: How Harry Williams Fought for Paiute Water Rights in Owens Valley

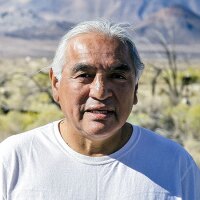

Late at night beneath a star-studded sky, surrounded by the Sierra Nevada and the White Mountains, circles of mourners sang and stamped their feet in the dust. The cry dance honored Harry Williams, Nüümü (Bishop Paiute) elder and internationally recognized expert in the ancestral water systems of Payahuunadü — Owens Valley.

In his lifetime, Williams was responsible for recovering knowledge of his tribe’s traditional irrigation networks and water practices, strengthening the Paiute’s claims for water rights in Owens Valley. His work as an activist for the health of his people and their homelands left a lasting impact on his community and on water management in the region.

The entire valley was our garden. Our ancient ditches made the groundwater rise. As we spread the water, our gardens grew.Harry Williams, Bishop Paiute elder and water protector

Harry Williams was born in 1956, exactly one hundred years after a U.S. government surveyor named A.W. Von Schmidt peppered his maps with clusters of marks indicating "fields of fine grass," with "first rate soils." At the time, Von Schmidt was unaware that he was recording ancient irrigation networks built by the Paiute tribes to cultivate massive, wild-tended botanical fields throughout the valley.

Growing up, Williams played along dried-out canals and climbed over rock piles once used as dams to capture water flowing from the mountainsides in his backyard. He knew his people’s creation story — that Coyote placed the People next to the water ditch (Owens River) — but little about prehistorical Paiute engineering. Centuries of his ancestors’ efforts to build and maintain vast networks of irrigated plots, some as large as two square miles, had been erased prior to his birth, in the space of two generations.

Regaining Paiute Water Knowledge

In 1863, Williams' great-grandparents were force-marched off their lands by the U.S. Cavalry to protect settlers who claimed Payahuunadü for themselves. Beginning in the early 1900s, Los Angeles city staff and agents, including a city engineer masquerading as a wealthy cattle rancher, systematically purchased property deeds and water rights. According to federal government records, Los Angeles "acquired practically all of the lands in Owens Valley in order to protect the watershed for the city’s water supply."

Paya is water. Water is life. The ranchers stole it from us. LADWP stole it from them.Harry Williams, Bishop Paiute elder and water protector

In 1912, President Taft’s Executive Order 1529 set aside 67,120 acres of lands for the Paiute, but political pressure from those in Los Angeles seeking to acquire even more Owens Valley resources drove the government to rescinded the offer. Instead, the Land Exchange Act of 1937 created three small reservations —Bishop, Big Pine, and Lone Pine — in a land trade between the federal government and Los Angeles that did not include tribal water rights.

As a young man, Williams' questions about an inherited history his elders couldn’t answer inspired him to seek out his ancestor’s monumental earthworks. Once he began his quest, he never stopped. Through decades of exploring every corner of Owens Valley, he developed a keen eye and intuitive sense for tracing the outlines of canals, ditches, dams and pools created over centuries by Paiute engineers.

Williams was introduced to Von Schmidt’s maps in 2011 during a guest lectureship with Pat Steenland’s "Water in the West" class at UC Berkeley. He met a student there named Jenna Cavelle, who had discovered Von Schmidt’s archives in the university library. Jenna and her partner, a Ph.D. candidate in environmental engineering, moved to Owens Valley and worked with Williams and local tribes to document extensive Paiute irrigation systems using GPS and GIS technology. Their teamwork resulted in an online interactive story map and the award-winning film "Paya: The Water Story of the Paiute", starring Williams.

The tribes learned to never take everything. Always give a little bit of water back, always offer a little bit of food back. If you took everything, then in the long run you’d have nothing.Harry Williams, Bishop Paiute elder and water protector

Williams' public speaking and ongoing fieldwork inspired ever-increasing numbers of tribal members, reporters, students, scholars and filmmakers to contribute to his efforts, culminating in the mapping of 60 ancient Paiute water networks. Yet Williams never believed his work was complete, and he continued to investigate and discover additional irrigation work as far north as Lunde Canyon, in a basin above Mono Lake.

The Draining of Owens Valley

Pre-contact, Northern Paiute irrigators supported one of the densest Indigenous populations in the region by engineering seeps and marshlands to cultivate native grasses, lilies, rye, sunflower, pigweed and dozens of other edible species. Their vast gardens also supported robust communities of deer, antelope, jackrabbit, native birds and fish. Endemic brine flies, gathered by the hundred-bushelful from Owens Lake, provided critical subsistence foods for the winter.

By alternating irrigated and dry years in their field plots, Paiute water engineers allowed the wild-cultivated plants to re-seed and propagate annually, and avoided creating the over-salinized and hardpan soils currently plaguing California fruit and vegetable farmers dependent on flood and furrow irrigation.

Today, 70% of L.A.’s water is sourced from the Owens Valley, through the annual export of hundreds of thousands of acre-feet of water. In contrast, the three Paiute tribes in the valley are allocated 8,000 acre-feet per year: a little over 3% of the original water volume their ancestors managed on behalf of all life in Payahuunadü.

As the original irrigators of Owens Valley, the Paiute should hold first users rights, a status accorded by California law to the original water users in a given area. The 1908 US Supreme Court Winters Doctrine also ruled that Congress must reserve sufficient water for any reservation created by federal law. Yet due to California’s arcane water regulations and inconsistent application of federal law, the tribes continue to struggle for groundwater, riparian water and Indian Reserved water rights.

Restoring Owens Lake

It is difficult to grasp the scope of ecological loss created and magnified by a century of water exports from Owens Valley to Los Angeles. Deer and antelope have largely disappeared from the valley. Once abundant native grasses are rare; the Owens pupfish has become a federally endangered species.

Patsiada (Owens Lake), once a 110-square mile waterbody navigable by steamboats, was artificially desiccated by the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1926. For generations, Owens Valley residents have been exposed to toxic air pollution from the dust in the dry lakebed, including arsenic and other heavy metal levels over a hundred times federal health standards. The dust — known as "Keeler fog"— was the largest single source of PM10 (particulate matter 10 microns in size) pollution in the United States and caused millions of dollars in economic losses.

Tribal members — including Williams, who died from respiratory complications — have long suffered from illnesses caused by the dust. Williams spent much of the latter years of his life working to address this public health crisis by repeatedly testifying in agency meetings. Teri Red Owl, director of the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission, credits Williams with orchestrating a chain of events that heightened federal pressure on the California Air Resources Board to require Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (LADWP) to invest in more expansive lake bed mitigation.

He was never afraid to speak truth to power. He attended innumerable meetings where he challenged the dogma recited by government decision-makers.Sally Manning, environmental director for Big Pine Paiute Tribe

Eventually LADWP reflooded Owens Lake. Algae and brine flies returned, followed by tens of thousands of migratory waterfowl. The lake earned the designation of Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network Site of International Importance in 2018. But the fight is not over. LADWP is currently seeking approval to pump groundwater from beneath the lakebed for continued reflooding measures, a move opposed by tribes and environmental groups, who fear the loss of remnant springs still extant on the lake.

In everything he did — cultural resource surveys and monitoring, expert testimony at agency meetings, lecturing on Paiute irrigation, soaking in local hot springs — Harry Williams' passion was paya (water). While serving on tribal and state boards, councils and committees, he tirelessly advocated for the protection, conservation and return of the lands and waters to the indigenous peoples and original resource managers of Payahuunadü.

Williams drew his last breath surrounded by family singing him into the next life with prayers and good medicine. Both the day he passed and the day he was interned, rainstorms swept through his beloved homelands, a fitting tribute to the life of a water warrior.

Alan Bacock, Sally Manning, Noah Williams and Teri Red Owl also contributed to this piece.