California Judges Don’t Reflect the State’s Diversity — How That Could Change

This story was published June 8, 2021 by CalMatters.

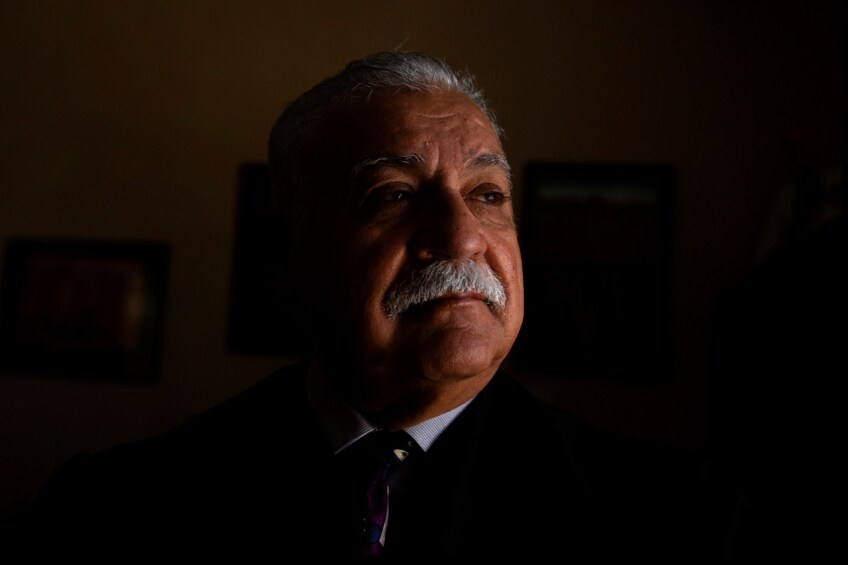

As Judge Juan Ulloa reflects on his life, his white mustache rises with his slight smile: The septuagenarian has come a long way from thinning and trimming cotton in the Imperial Valley for $1.25 an hour.

Not that becoming a Superior Court judge was easy. Ulloa wasn’t appointed by a governor, although he tried. Nor was he recommended by the local bar, though he tried that too — he figures his legal work representing employees in discrimination suits and inmates seeking better jail conditions deemed him “too radical” for an aspiring California judge at the time.

Instead he took the most political route possible: knocking on doors asking for votes.

His approach created a blueprint that’s been replicated by potential judges of color in Imperial County ever since. Four decades ago, all of the county’s Superior Court judges — the ones who handle everything from drunk driving to murder cases— were white. Now, 60% are people of color, making it uniquely diverse among California’s Superior Courts.

For years, the homogenous nature of the state’s roughly 1,600 Superior Court judges has been an issue. Whites make up 36% of the state’s population but 65% of its Superior Court judges. Latinos, a plurality of the state at 39% of the population, hold only 12% of its Superior Court judgeships. And in four majority-Latino California counties — Colusa, Kings, Madera and Merced — there are simply no Latinos on the bench.

The gap matters. A diverse bench can lead litigants to feel more trustful of the judicial system. And some research demonstrates that having judges from different ethnicities and backgrounds can also affect case outcomes.

Determined to shake up the status quo, advocates of judicial diversity are trying an array of strategies:

- In Imperial County, where Latinos are 85% of the population, judicial elections have become like never-ending musical chairs — seemingly as soon as a governor or voters select a judge, other lawyers, often attorneys of color, plan to run for that judgeship.

- In Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area, legal professionals are going inside classrooms, mentoring students of color whom they hope will choose a legal career. State lawmakers are considering funding this non-profit program, now operating under the Foundation of Community Colleges, statewide.

- Other attorneys are helping people of color skip law school altogether — taking advantage of the fact that California is one of the few states that allow would-be lawyers to substitute a legal apprenticeship for a pricey law degree.

How Are California Judges Selected?

Despite inequities in Superior Courts, the state’s Supreme Court is more reflective of California: fully 71% of its judges are people of color, creating one of the most diverse Supreme Courts in the country.

The governor names appointees to the Supreme Court, but also appoints the vast majority of lower-profile state Superior Court judges, drawing from a list of names typically prepared by the governor’s judicial appointments secretary and vetted by local appointment committees throughout the state. Those appointed California judges must then appear on the ballot in the next even-year primary election if someone surfaces to challenge them. And they must garner at least 50% of the vote or advance to a general election.

Any time sitting judges are up for election, challengers can take a shot at defeating them. And some judges time their retirement close enough to an even-year general election to sidestep the appointment process, instead allowing local attorneys to run for an open seat.

Regardless, once a judge wins voter approval, that judge has earned a six-year term.

“Appointed judges, particularly those with long or lifetime tenures, have the advantage of greater independence. After their initial appointment they are more insulated from political pressure, but they have little or no accountability,” notes David A. Carrillo, executive director of the California Constitution Center. “The reverse is true for elected judges, who have the advantage of greater accountability to the voters through the retention or reelection process, and the disadvantage of decreased independence due to their close connection to the political process.”

California’s method of choosing judges — combining appointments and elections — offers what he terms “a middle ground.”

Imperial County: “We Proved It Could Be Done”

Contentious elections have been critical to transforming the bench in Imperial County.

Located just 17 miles from Mexicali, Mexico, the California town of El Centro is the seat of rural Imperial County, where Latinos have been a majority for decades. White people long dominated the bench. In 1980, then-Gov. Jerry Brown appointed Matt Contreras to be a judge of what were then called Municipal Courts. Contreras became the county’s first Latino judge — and the only one for another decade.

By 1990, Juan Ulloa, having been skipped over for an appointment, bypassed that traditional process and gambled that voters would elect a Latino judge.

“It was common wisdom,” he said, “that it couldn’t be done.”

That year, a Superior Court judge retired, clearing the way for Ulloa to run for a newly vacant seat. He lost. Four years later, another judge retired, and Ulloa ran again, facing off against Roger Benitez, now a federal District Court judge best known for rejecting California’s assault rifle ban.

Since the state began collecting diversity data on judges 14 years ago, governors and the voters have helped Imperial County go from two Latino judges in 2007 to five in 2020 — rising, falling and coasting along the way.

Now Latino judges make up half of the 10-member bench. Two Latino judges were appointed by Brown, one in 2016 and one in 2018. One was appointed by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2009. The other two won in elections.

Said Ulloa: “Once we proved it could be done, the doors opened.”

In all, 40% of Imperial County’s judges first got the job by campaigning for election. That’s exceedingly rare in California, where counties can go decades without a Superior Court challenge.

“The Imperial Valley is such a close-knit area that people want to make sure they know who they are electing,” said Judge William Quan, an Asian American native of the valley. Quan ran twice, losing once before and winning in 2014.

“You learn to appreciate that. And maybe that has bred this thinking that I will run for election versus appointment because we understand the people. We know them and we’re comfortable enough to be able to ask for their support.”

It was common wisdom that it couldn’t be done.Judge for the Superior Court of Imperial County

While elections can diversify a bench, they can also have the opposite effect. Latina Judge Ruth Bermudez Montenegro, appointed by then-Gov. Brown in 2012, was unseated by Judge Brooks Anderholdt in a primary election a mere few months later. Eventually she won another judgeship and now is a magistrate judge for the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California.

“We’ve gone from seven white male judges, to now we have two Hispanic females, an Asian male, and three Hispanic males to round out our 10 judge bench,” said Ulloa. “We reflect the community pretty much.”

Even so, there remains a more than 30 percentage point gap between Imperial’s Latino demographics and its judiciary.

And that helps explain why others see the lack of diverse judges as a problem with systemic roots.

Creating a Pipeline for Future California Judges

Across California, there’s a shortage of diverse judges in part because there’s a shortage of diverse attorneys. Case in point: In a state where Latinos make up 40% of the population — outnumbering all other groups — only 7% of California’s practicing attorneys are Latino.

It’s a problem Ruthe Ashley has been chipping away at for years.

“We were thinking, we will recruit diverse attorneys out of law school,” said Ashley, executive director emeritus of California Leadership-Access-Workforce, a program for students interested in a legal career. “Well, there weren’t enough in law school because they weren’t getting into law school. So, we started looking at the pipeline.”

The program, launched in 2015, now operates in 21 high schools across the state.

Its goal: guide students from high school to community college to law school.

One of those students is Manjinder Kaur, who recalls that she was negotiating a plea deal for her imaginary client at De Anza High School in Richmond when she decided to become an attorney.

Kaur, who is Sikh, started plotting her path toward what she termed her ultimate goal: becoming a judge.

A first-generation college student, she started at Contra Costa College and graduated from San Francisco State University while working full-time. She recently finished her second year at the University of San Francisco Law School.

“I feel like, because I got a letter of recommendation from (Ashley), I got accepted into a lot more schools,” she said. “That really helped me.”

Nonetheless the program’s scope is limited. It’s mostly concentrated around Los Angeles and the Bay Area. Only one high school in the Central Valley participates, although the valley suffers from one of the most acute lawyer shortages in the state.

We were thinking, we will recruit diverse attorneys out of law school. Well, there weren’t enough in law school because they weren’t getting into law school.Ruthe Ashley, executive director emeritus of California Leadership-Access-Workforce

State Sen. Richard Roth, a Democrat from Riverside, is pushing legislation that would have the state spend $10 million to expand the program to more locations statewide.

“It has essentially been operating with volunteers,” Roth said. “If we expect to move the needle dramatically — and frankly, we must — we need to do more, and we need to do it now.”

Roth’s SB 770 bill would also require the chancellor of the California Community Colleges to report outcomes to the state, something the program hasn’t done previously. It has yet to be incorporated into the Legislature’s whopping $264 billion proposed budget.

Still other Californians have an entirely different approach: Bypass law school and its six-figure price tag, and opt instead for apprenticeships.

The Apprentice — a Different Path to a Law Career

Lauren Richardson, a 34-year-old Black woman, wanted to be an attorney for as long as she can remember. “I just always thought I was just going to die wanting to be a lawyer,” she said. At age 19, she became a single parent, forced to juggle raising her son while taking college classes.

“I didn’t have an easy runway to graduate from college, law school and pass the bar,” she said.

Then she learned about the California State Bar Law Office Study Program, which permits aspiring attorneys to learn the law by working under an experienced attorney.

California is one of four states — along with Vermont, Virginia and Washington — that allow people to become lawyers without law school. It takes at least four years of training, and apprentices must pass the First Year Law Student Exam (the baby bar), recently made famous after Kim Kardashian West revealed that she’d failed it.

In 2019, 38 California apprentices took the baby bar and 31% passed. Last year, 42 apprentices took the exam, and only 14% passed.

After their apprenticeships and before becoming lawyers, aspirants must eventually pass the actual bar exam.

Richardson is a part of Esq. Apprentice, a nonprofit helping low-income women of colortrain to become attorneys. UC Berkeley Law graduate Rachel Johnson-Farias started the program after working with young people to seal their juvenile records. Many of them were “already lawyers in their own right,” after spending years navigating California’s justice system, she said; they understood the law.

Today Esq. Apprentice has a cohort of five women of color working to become attorneys. Still there are challenges.

Richardson has an attorney mentoring her. But her years of attending different colleges and taking different classes failed to meet the State Bar’s course requirements. Instead she took three standardized tests.

“The State Bar called me back and said one of these tests that you took is the wrong test,” Richardson said. Shortly thereafter, the pandemic hit. “There’s always a hurdle or a box you have to check or something.”

The program is a page out of the United Farm Workers’ 1970s legal strategy. Founded by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, the agricultural union has been training apprentices for decades, creating a pipeline for future union attorneys and possible judges. Decades after Chavez’s vision, then-Gov. Brown appointed Judge Marcos R. Camacho — a former farmworkers’ union apprentice — to the Kern County Superior Court bench.

Also getting into the act: the Judicial Council, the policy-making body of the California courts. It created a toolkit to help judges mentor young attorneys, and to explain what attorneys should expect when applying for a judicial appointment.

As Californians search for solutions to diversify the bench, litigants and communities are living the extremes. In rural Colusa County, as one Latino defendant noted, people like him “have only seen a Latino judge on TV.”

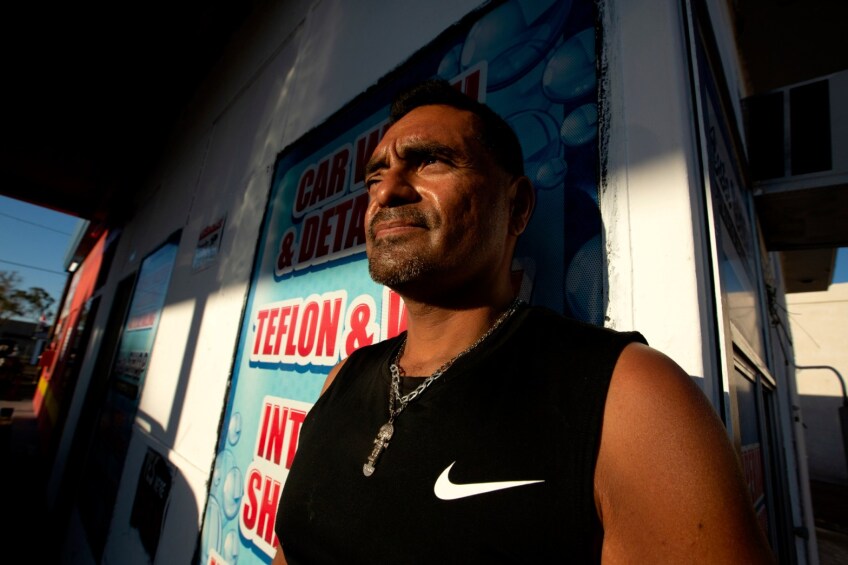

But hundreds of miles away in Imperial County, Michael Torres is accustomed to judges who look like him. Torres, who calls himself a “reformed career criminal” at age 46, chuckles a bit when asked about Judge Ulloa, whom Torres has known since he was a child, when Ulloa was his catechism teacher.

Torres sums up Judge Ulloa in two words: “strict” and “fair.”

For the record: This story was corrected to reflect the number of California apprentices who took, and passed, the baby bar.

Find part one of this story here: In Absentia: No Latino Superior Court Judges in These Majority-Latino California Counties

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.