After the Lawn: Managing the Parkway

Parkways are one of the smallest sections of open ground to be found in most gardens, yet they are the trickiest. Most of us have heard the joke calling these curbside gardens "hell strips." Beneath their typically compacted earth are meters, water mains, sewer pipes, and gas lines. Engineered in and around them across much of the region are catch basins for storm drain systems. There might just be a street sign, fire hydrant, or utility pole. On the surface grow the most heat-blasted, least irrigated plants in our gardens, typically turf and street trees. Parkway turf is the hardest working grass outside of school soccer fields, trammeled daily by passengers from cars and delivery trucks, pedestrians, children, and dogs. Recent campaigns have also pushed their use as vegetable gardens, native grass savannas, and agave-and boulder-stuffed desert-scapes. Typically owned by cities, but managed by homeowners, parkways are subject to a variety of regulations from a number of utilities and city agencies, including street services, building, and safety and sanitation.

Hell strip, indeed.

Most challenging for those of us tending them, parkways now amount to the next big frontier in outdoor urban water conservation. For most properties, parkways are the last points where rain draining from our properties might be caught and the first places that stormwater from the street might be imported.

If the parkway has an equivalent in a wild setting, it would be a stream bank. To better see that, refer back to the hardscape map in Part 2 and this week's grading and drainage schematic. In the imaginary 5,000 square foot lot pictured for this series, more than 2,600 square feet are covered by pavement or structure. In other words, more than half is impervious to water. This ratio is typical of real-world lots across the Southland urban grid. This year, with local rainfall of roughly nine inches, more than 13,000 gallons of imaginary water would have hit the imaginary hardscape, then traveled through downspouts, across the driveway, and into a street-side gutter for delivery to storm drains and the Pacific.

Drought? What drought? This is the equivalent of three months of average daily water use for an Angeleno. Real quantities like this rolled off real homes into the storm drain systems across Southern California with every rain this winter.

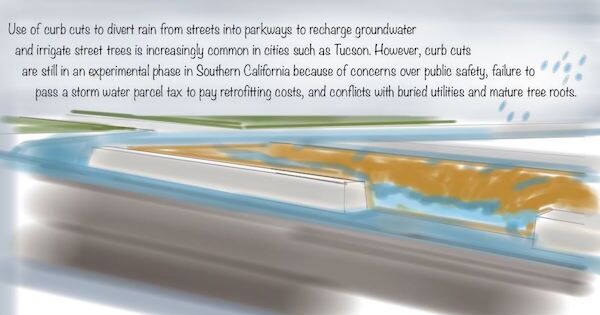

But the amount of water we let flow off our lots doesn't touch the volume flowing by them that could potentially be diverted from streets into our yards. The first thing anyone interested in availing themselves of this free water should do is read the book of Tucson landscape designer Brad Lancaster. Since popularizing curb cuts and street-side water traps, or swales, in his Arizona hometown, Lancaster has convinced utilities and local government agencies to work with desert homeowners to use curb cuts to, in effect, "amplify" local rains for land near paved spaces. No cloud seeding needed, just a shovel and a concrete saw. He is being increasingly sought by agencies such as the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works and the non-profit WaterLA to participate in think tanks and advise on parkway conversions in Southern California.

"The challenge," says Lancaster, "is: Can you make a system that can infiltrate the water quickly enough and have enough capacity?"

According to the City of L.A.'s Watershed Protection Program Manager Shahram Kharaghani and his department's landscape architect Deborah Deets, they're working on it. Calls for outdoor water use cutbacks by the L.A. mayor and California governor have long ago lost the ring of recommendation and gained the tone of command. L.A. agencies recently reduced irrigation to municipal landscapes and parkways from the legal three-day cycle to two days a week. The next shoe to drop may be cutting off irrigation to these sites completely.

"We're on a precipice," says Deets. "We have all these crises driving us: Aging infrastructure, urban heat island effect, drought, pollution. Then we have opportunities. We're always repaving our roads."

Retrofitting parkways is ideally done when repaving crews come in to do blacktop and sidewalk repairs. Deets' eyes and ears are wide open for curb alteration designs that could be incorporated in street work and tailored for the region's wildly various grades, soil types, and streetside infrastructure. Helping her department piece together a region-wide idea tree are students from Cal Poly Pomoma's 606 Studio masters program in landscape architecture. "We are trying to engage engineers, landscape architects, designers, biologists," she says. "We want to get ideas on the table." Fish around for student work on the potential of stormwater capture in L.A. and from 2009 you find one of the better studies on the subject by (then) L.A. Department of Public Works intern and UCLA masters degree candidate Haan-Fawn Chau. For those of us older observers who have for years been frustrated by the slowness of infrastructure design changes, the drawing in of students to the issue is reason for optimism even in drought. Where the critical thinking of a mass of young town planners leads, hopefully one day city policy will follow.

It will happen after a long leap from prototypes to standardized plans. "When you put in a standard," says Deets, "you're telling people they should do it." Here the duty of the city is high. Anyone can create a curb cut. Kharaghani and Deets have to design the kind where passengers stepping out of cars then don't fall into ditches next to the cut. Other design challenges include the need for culverts to withstand the pressure of moving water without collapsing. Soil in often-compacted sites must be nurtured to become absorbent. Southlanders must develop a new, more ditch-loving aesthetic. A zone traditionally home to buried utilities will have to make room for infiltration pits. Hardest of all, we must find money to do the work.

A long campaign on behalf of a proposed parcel fee to help kickstart retrofitting by Heal the Bay and other watershed activists was stymied in 2013 by anti-tax protests to the L.A. Board of Supervisors. How long the region sits on its wallet may depend on how dry it gets. Or maybe not. Of all places, apart from Tucson, some of the best parkway harvesting has come from a place famed for wetness. The City of Seattle aggressively converted parks to seasonal flood zones and retrofitted entire neighborhoods for stormwater capture in an effort to protect the salmon fisheries of Puget Sound from stormwater carrying urban pollutants.

Here in Southern California, parkway harvesting has reached a kind of cult status among non-profits such as TreePeople, Northeast Trees and the Council for Watershed Health, each of which boast promising but all too rare "green streets" and open spaces that bank stormwater such as the Elmer Avenue and Oros Street projects and Garvanza Park. Among relative newcomers to the cause is Melanie Winter, a long-time L.A. River advocate. Her new charity, WaterLA, has been working with agencies and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power to streamline curb cutting permits. Also forging ahead on curb cuts, often in classes in partnership with water districts and the Surfrider Foundation, is the garden design collective G3 Green Gardens Group.

As planners noodle design challenges and change-agents proselytize, a workable and cheap parkway protocol for homeowners to use to harvest rain remains elusive. Those intent on making parkway curb cuts now should contact their city's department of public works and prepare for an expensive permitting process.

My own parkway recommendation for those undertaking rebate gardens now is to take a Do No Harm approach. Remove turf around the root zones of existing street trees, mulch, and deep water them as described in Parts 3 and 4. Follow the decomposed granite pathway formula from Part 6 in providing a generous walkway no less than five-feet wide from curb to sidewalk. Adding the square footage to a turf-removal rebate form should easily cover the cost of materials. The path should safely and easily accommodate wheel chairs or combinations of an elderly person with a caregiver or a parent with a toddler and stroller. During installation, observe the City of Los Angeles guideline to keep the pathway flush with the curb and sidewalk. The placeholder parkway schematic curves the access path to leave as much room as possible to the tree root zone and soil-building mulch but still maintain a direct route from path to home.

Think twice about replacing parkway turf with gravel and cactus. Gravel moves underfoot, making it a slipping hazard in a trafficked spot. Shade trees and cacti do not belong in the same eco-system, even in a fake urban one. Most importantly, remember that the heat and glare bouncing off the gravel drive evaporative water loss by making a hot, dry place hotter and drier.

In parting, this piece closes with a preview sketch for the next installment of After the Lawn. In this drawing, the phase one rebate garden recommended in Part 6 and this week's placeholder parkway sketch both evolve. This future plan anticipates that, in four of five years, the lavender of the first post-lawn site is ready for editing (even replacing). It suspects that the benefits of the rain barrel system have intensified a gardener's interest in breaking up hardscape and reshaping ground to spread water in a more natural-looking system. As a timeline, it anticipates a five-year-long transition to fully integrated rain garden. This allows gardeners to test their ideas for maintenance needs, resource efficiency, aesthetics, costs and safety. As is so vividly the case with parkways, working the frontline between water waste and conservation under our stubbornly blue skies is an evolution, not a makeover.

Follow the entire After the Lawn series:

After the Lawn: Part I

Designing Your New Garden

Caring For Your Turf

How to Remove Your Lawn

Planning Your New Garden

How to Design Your New Garden

Managing the Parkway