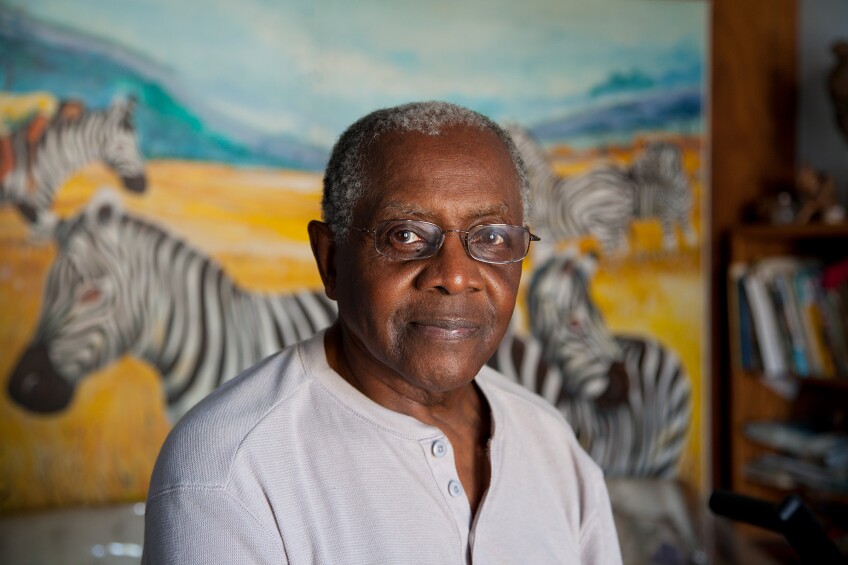

How The Murals of Elliott Pinkney Captured the Creative Energy of Compton and Beyond

At schools, churches, art centers, auto shops, health centers, and in neighborhoods, artist Elliott Pinkney painted bold swaths of color and every shade of brown reflected in the community. The murals he designed across Compton in the summers of 1977 and 1978 mirrored the creative energy and consciousness of the city. His art extended into Watts, South Central, Long Beach, Carson, Lynwood, and Berlin, Germany, in over 90* murals across 50 different sites, many of which involved a total of over 200 local youth (*multiple murals painted at one site were counted as individual murals; in a career that spanned over 50 years, this total was likely higher).

Pinkney was a gifted printmaker, graphic designer, poet, and multimedia artist. Featured nationally in nearly 40 exhibitions, and in museum and private collections, Pinkney’s contributions as an artist, mentor, and teacher impacted generations of artists and community members, making him an essential part of the arts and culture of the region and state.

Born in Brunswick, Georgia, in 1934, and raised there through the 1940s, Pinkney settled in California in the 1950s, after being stationed with the U.S. Air Force. His artistic gifts led to graduating Magna Cum Laude from Woodbury University with a Bachelor’s of Professional Art and working for decades as a local Art and Printing Director. After meeting and marrying his wife, Louise, in the early 1960s, they became a part of the new group of Black homeowners in Compton and raised three boys there. While walking near his home, Pinkney met John Outterbridge, director of the Compton Communicative Arts Academy, and became one of the academy’s “artivists.” The Academy and the multitude of Black artists it welcomed like Pinkney ignited Compton as a force for art and creativity.

Making city walls his studio

In the 1970s, Pinkney brought his talents as a printmaker and painter outdoors. In 1972, he painted the “Mafundi” mural at the Mafundi Institute on Wilmington Avenue and 103rd Street in Watts. The mural displayed the face of a Black child silhouetted by Black profiles and “MAFUNDI,” Swahili for “artisans,” in black lettering above it. Pinkney’s use of bold silhouettes would prove a signature motif that evoked intergenerational and community connection.

In 1997, the City of L.A. attempted to whitewash it, but the colors bled through, and they then asked Pinkney to restore it. The Mafundi mural played a part in the building’s recent designation as an L.A. Historic-Cultural Monument. Through the mural’s longstanding presence, Pinkney made Watt’s artistic history visible across generations.

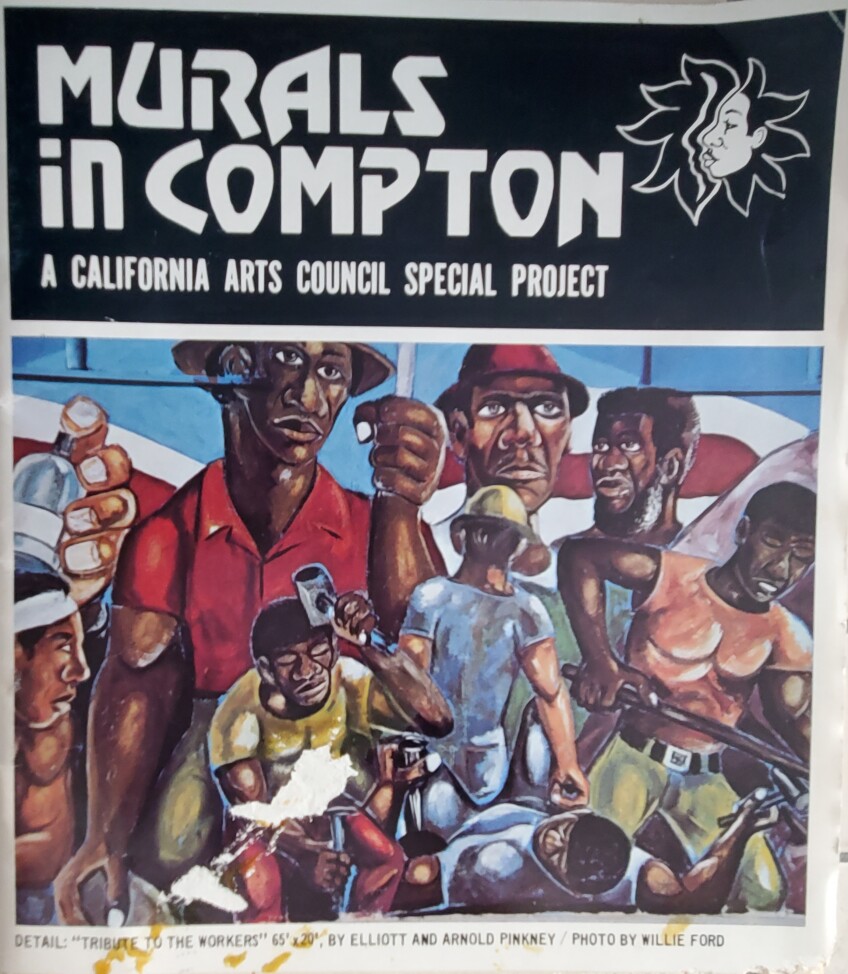

In Compton, Pinkney made the walls of the city “his studio for the summer and winter of 1977 and ‘78.” He began the first and only known documented citywide mural project. His eldest son, Arnold, a teenager at the time, joined him for the project; several murals bear both father and son’s names. The murals portrayed multicultural, intergenerational, and ancestral figures, Black culture and pride, and multiracial civil and workers’ rights leaders and movements. In “New Worlds,” one of two murals he painted at the Charles Dickson Studio, he evoked Afrofuturistic images of space and technology, a Black cultural cosmos of families, elders, astronauts, musicians, and day-to-day folks with afros that haloed like planets. Dickson, an acclaimed sculptor and longtime friend, whose work and ideas influenced the future-facing theme of the mural, shared that neighbors “would come by and teach their kids about art and how the mind works, through his art.”

Funded by the California Arts Council, Pinkney documented the project in “Murals in Compton,” a booklet he designed and printed, complete with a map, poetry and photos taken by Arts Academy Photographer, Willie Ford, Jr. In the 1980s to 1990s, he added more art to Compton’s landscape, including “5 Pillars of Progress,” a series that enlivened large concrete pillars near Compton College.

The map above displays locations and images (when available) of both active and inactive Elliot Pinkney murals (some murals may not appear due to unavailability of information or mural address).

Empowering young artists

Pinkney sought to encourage as many youth as possible through his work. In Long Beach, beginning in the 1990s, he guided groups of 20 or more youth in painting murals during the eight-week Summer Youth Employment Training Program (SYETP). Heather Green, an artist and retired Long Beach Mural and Cultural Arts Program Supervisor, implemented the SYETP mural arts program. According to Green, Pinkney’s “work spoke with and for the people.[It] was lovingly direct, gentle and lyrical, [and] part of the human spirit that Elliott so kindly shared … [Youth] in the community saw what it looked like to be an artist in the community and grew up with a sense of the impact of community art.”

Jose Loza, a Long Beach-based artist, muralist and high school arts teacher, was one of the SYETP youth that Pinkney mentored. Working with Pinkney influenced his artistic practice: “I've really tried to adopt a lot of the ways that he was with community…He would take the time to explain what he was doing, what your role was within the projects…As a kid that just seemed like wow, he's talking to me like I matter, like I can do this.” When Loza participated in his first art exhibition as an adult, he invited Pinkney. To his surprise, he showed up.

Artist Man One, who recently completed the “Faces of Watts” mural series just a few blocks from the Mafundi mural, worked as a SYETP Co-Teacher with Pinkney one summer. He recalled that Pinkney was “always about unity, always about bringing people together from different backgrounds.” He admired Pinkney’s patience to get the energetic students “to settle down and learn from him and pick up a brush.” Separate from the murals he crafted on his own, Pinkney simplified the process so that students of various experiences could engage in the joy and technique of painting.

Translating history through art

Pinkney contributed to L.A.’s title as mural capital of the world in the 1990s. The Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC), founded by artist and recent National Medal of the Arts recipient Judy Baca, commissioned Pinkney for several murals that reflected L.A.’s diverse ethnic communities, including “Don’t Move Improve” (1984), “All That You Can Be” (1990), and “Visions and Motions” (1993). Artist and former arts administrator Alan Nakagawa worked with Pinkney through a SPARC summer youth project and later through Pinkney’s Metro Art installation at Washington Station. He noted, “if you look at his installations, [they] were very abstract…But when it came to his murals, he knew which language he needed…he spoke different languages in the arts. Most people only have one language. He had several.”

Pinkney represented the important role of muralists as historians and storykeepers. In “Spirits of America,” part of the “Murals in Compton” project, he depicted images of workers alongside civil and laborer rights leaders. Today, the mural decorates Compton YouthBuild, where students view it daily. Compton-based Artist Mel Depaz connected to his work when she was asked to retouch it: “I love his painting style…the brush strokes…move in the direction that the character is moving. His color choice is really vibrant and rich…I felt honored to be able to retouch one of his works. He’s a legend in Compton and mural history.” In Long Beach, the “Community History” mural, painted with 28 Long Beach youth, recalled key community leaders and activists, like Ernie McBride, co-founder of the Long Beach NAACP Chapter.

Defying time

Anyone who has lived or traveled in Los Angeles, Long Beach, and communities in between, has likely seen or have been visually impacted by an Elliott Pinkney mural. In Compton, few of his murals remain intact (“Medicare ‘78” and “Spirits of America”); another gets regularly covered with graffiti art on its lower half, leaving the top and the people it depicts (“Ethnic Simplicity”). All of these murals were part of the original “Murals in Compton” project that Pinkney began 47 years ago.

Long Beach is home to the majority of his remaining murals, followed by Los Angeles. Whereas Compton currently has no mural ordinance or preservation policies, Long Beach and Los Angeles have benefitted from years of public arts advocacy such as the work of Green in Long Beach, Judy Baca of SPARC, and Isabel Rojas-Williams of the Mural Conservancy of L.A. Pinkney painted murals across cities and generations, as small as the “Peace and Love” door at the Watts Towers campus, as towering as the figures of the “Evolution of the Spirit” at L.A. Southwest College. He designed numerous posters for the annual Watts Festival of the Drum and Metro Art, as well as and public sculptures, such as the glass "Dolphins” installation that once decorated downtown Long Beach and the “Running for the Blue Line” metal figures still on view at the Metro Blue Line Washington Station.

Pinkney passed away in December 2019. He spent decades seeing the community for the beauty it contained and using his gifts to reflect that beauty back to itself. Nakagawa called Pinkney “integral to the L.A. arts, [one of its] top 10 muralists. Easily.” He lived in the same house, painted blue, “his favorite color,” Mrs. Pinkney shared. The front gate resembled the doors of the Academy, the inside an exhibition of personal works and accolades. Out of all of them, Mrs. Pinkney’s favorite piece was an assemblage made from wall clocks, arranged with care. The clocks no longer work, no longer mark the time. The artist defied time, through the art and community he created with it.