The Lady of the Lake: The Depression Era Roots of Echo Park's Unofficial Patron Saint

The newly renovated Echo Park Lake is a vastly different place from what it was two years ago. The contours of the 29-acre park are roughly the same, but the whole place has been reinvigorated -- the once muddy, sludgy water that filled the man-made lake is now sparkling and clear, the lily pads are bright green, the new playground sleek and safe.

Today, it is warm, and the park is filled with a mixture of people that reflects the diverse population of the surrounding neighborhood. Latino children play on the playground while teenagers in all black huddle together under the trees. Twenty-somethings with beards and tattoos picnic on the lawn, and older couples stroll along the lake's perimeter. By the boathouse, a toddler happily shrieks in Spanish as a couple, who look to be straight out of an alt-country band, let her use a remote control to navigate a tiny toy sailboat which sails precariously close to the spew of the fountain that rises like a geyser in the lake's center.

The park's rebirth is one of L.A.'s great public works success stories of the new century. Overlooking it all, on a concrete peninsula with benches facing the water, is a fourteen-foot, Art Deco-style female statue. Her official name is "Nuestra Reina de Los Angeles," which means "Queen of the Angels," but most folks in the neighborhood know her simply as the "Lady of the Lake." She was born of civic-minded ideology in a time of dire straits and social strife. She represents our country at its best and most unified, and looking out on the lawns filled with citizens of all nationalities and economic classes, it seems she couldn't have picked a better spot.

Ada May and Uncle Sam

By taking the simple attitude that artists want both to work and eat, and that the public needs their contribution to civilization, Uncle Sam has started a real art movement. Instead of a lot of gush about the "sweet mystery" and uplifting influence of art which well fed "art lovers" have fed to starving artists in lieu of hard cash, Uncle Sam proffered a modest but regular pay check. --Arthur Miller, The Los Angeles Times, February 4, 1934

Artists are blossoming under this genial and broad minded government patronage, just as the artists of the renaissance bloomed under kings and dukes. -- The Los Angeles Times, January 18, 1934

The sculptress of the "Queen of the Angels," Ada May Sharpless, was born in 1904 in Hilo, Hawaii, and moved with her family to Santa Ana as a small child. A smart, brave and artistic girl, she bucked the old marriage trap and graduated from the University of Southern California in 1922. After studying at local art schools, she sailed for Paris where she studied under the sculptor, Emile Antoine Bourdelle, and worked in a studio on Rue Boissonnade. Right in the middle of the American expatriate scene in Paris, she exhibited at both the prestigious Salon des Independents and the Tullieries. When Ada finished her European adventure in August of 1929, the Los Angeles Times noted that the "Trojan Co-ed" had returned to Southern California and had "the hope of fixing some of its beauties in stone."1

She couldn't have picked a worse year. On October 29, a day forever immortalized as "black Tuesday," the stock market crashed, knocking the economy into the gutter and sending millions of Californians right there beside it. As the years passed and the Depression deepened, Ada worked diligently in her studio at 1142 ½ Seward Street, while President Hoover's laissez-faire philosophy did little to help the suffering or the nation's economy.

The Los Angeles Times art critic, Arthur Miller, considered the flagging L.A. art scene, made up of "art associations, women's clubs, and endless abortive talks, teas, and schemes," almost as dismal as the nation's finances.2 In 1930 he found the 21st annual exhibition of the California Art Club at the Los Angeles Museum in Exposition Park so dismal that he asked rhetorically, "Why should the major art organization of Southern California offer for public view a thoroughly mediocre exhibit of its members' works?" The only bright spot he saw in the whole show was a sculpted torso by Ada May, which he raved, was "easily the star of the show."3

Study the contours, the exquisite movement of the trunk on the hips creating moving lines both before and behind in which truth meets beauty. You can call it real, or classic, or the seizure of a fleeting impression of movement. Call it what you like, this piece of work will out last the label. It is art that indicates real feeling and a cultivated mind.

When Roosevelt took office in 1933, the Federal government quickly began to implement his promise of "a new deal," focusing on the three R's: relief, recovery, and reform. Edward Bruce, a powerful banker and amateur painter, believed relief should extend to creative artists. With the full backing of the Roosevelt administration, and an extra nudge from the first lady, The Public Works of Art Project, called P.W.A.P, was funded for an initial two month period starting December 15, 1933.

It was the creative kick in the Angeleno pants that Arthur Miller had been praying for.

Under the auspices of the federal Treasury, the P.W.A.P divided the nation into sixteen regions, each with its own governing committee. Southern California's 14th region committee was headed by Merle Armitage, and featured such luminaries as Cecil B. DeMille and Arthur Miller himself. Artists were encouraged to bring examples or photos of their work to the committee headquarters at the Dalzell Hatfield Galleries downtown. For a wage of $15 to $26.50 a week, selected artists were given remarkable freedom with few parameters. According to Miller, "The local committee hit on the idea of asking artists to spend their time making pictures, sculpture, prints and so forth which would, when finished, prove acceptable to schools, libraries and other public places."4 Ada May was one of the first artists accepted into the program, which put 60 sculptors, metal craftsmen, lithographers, painters, and wood engravers to work in its first week.

The program was an immediate hit, and by January over 600 hundred "artists" had applied at the Hatfield galleries, although only 100 were accepted. Schools and institutions were encouraged to apply for works of art, and began drives to pay for the artists' supplies and materials which the federal government did not fund. Several trendy mural painters offered their time for free, using assistants supplied by P.W.A.P. Two large-scale projects -- a fountain dedicated to "Water Power" in Lafayette Park, and the 40-foot Astronomers Monument at the under-construction Observatory at Griffith Park -- were also begun by teams of sculptors and their assistants.

The effect on downtrodden and unappreciated artists was invigorating. No longer having to scrounge around for "day jobs," the competition for slots inspired artists to bring their A-game, knowing they were required to frequently present their new works to the board. For the Santa Monica library, P.W.A.P. volunteer S. MacDonald Wright started on a fantastical 200-figure mural, celebrating "Technical and Imaginative Pursuits of Early Man," using $1000 of materials raised by the city. It was a uniquely California affair. The actress Gloria Stuart modeled for the soundstage section, a pro-wrestler who loved Beethoven posed for many other figures, and the background featured realistic representations of coastal California flora and fauna.

To celebrate this massive output, a large scale exhibition at the Los Angeles Museum was planned to show off some 300 works of art from the program's inaugural two months. According to an exuberant Armitage, it would "be the most important group of works of art ever created and exhibited by any group of Southern California artists."5 Over 3,000 invitations were sent out for the opening on March 4, 1934. "One of the most important art movements in this country is, in my opinion, developing now in Los Angeles," Edward Bruce exclaimed via telegraph.

P.W.A.P. vs. the Powers That Be

I know I promised "dispassionate criticism." It can't be done. There ain't no such animal in the face of what our artists have created. They've got the stuff. Uncle Sam gave them their chance. They came through. That show is young, vigorous, colorful and varied. No other region will make such a showing. A director of another region exclaimed "It's incredible. New York can't compare with this. I'm going to wire to Washington that Southern California artists have got them all beat!' -- Arthur Miller, The Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1934

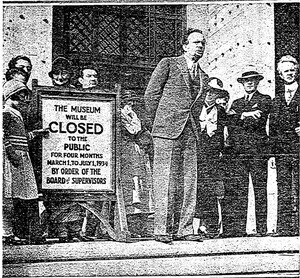

The show was curated, with all the works, including Ada's "lovely"(according to Miller) three figure sculpture, as "Government Protecting Industry and the Home." Sketches of the murals being created at places like Hollywood High spread across seven galleries on the museum's ground floor. A breathless preview written by Miller had already been in the Times and then -- the cold hard realities of the Depression. The county was broke. "High culture" was seen as frivolous and expendable. So on March 2, just two days before the exhibit opened to the public, the county voted to shut the doors of the Museum for four months as a cost cutting measure, leaving the galleries darkened, with only the Museum director and his assistant left as caretakers.

There was an immediate uproar. Bruce, Armitage, and Miller were all furious, and disappointed. Armitage railed: "To close the museum at this time will cost the community more in actual cash -- not to speak of loss of prestige as a cultural center than the amount of money needed to keep it open." Many folks signed a petition protesting the museum's closure. On Sunday, the day of the aborted opening, hundreds of art lovers gathered in Exposition Park to protest the Board's decision. Leaders in L.A.'s art community speechified on the Museum steps. The disappointment in the air was palatable.

In the work of these artists is perhaps the birth of an American renaissance in painting. And Los Angeles has the unfortunate part to play of closing the doors of the museum on the day this new era perhaps was to begin. -- Los Angeles Times, March 5, 1934

But all was not lost. A few days later a savior of the old school, gilded age variety came forward. New York millionaire Samuel H. Kress, who had loaned the museum a times-typical exhibit of Old Masters, donated enough money to partially reopen the museum for two weeks (it was soon extended to April 15). The Federal Art Exhibition was immediately a record-breaking hit, with 75,000 people attending in the first twelve days. Here was art they could understand -- large-scale, patriotic, populist (some would say leftist), prideful, historic, and centered on real American people instead of imitations of earlier, grander periods.

P.W.A.P's funding was extended until April 28, continuing on a smaller scale under the newly formed Federal Emergency Relief Administration and the state. Ada continued on the government payroll and on June 1, announced the completion of her most ambitious clay sculpture, the "Queen of the Angels." The federal government then donated the statue to Echo Park in June, and funds to cast the statue in bronze were secured. However, it was eventually molded with a new cost-effective Depression era favorite -- poured concrete, or "liquid stone," as was the famous "Santa Monica" statue, the Astronomers Monument, and the Lafayette Fountain.

In the winter of 1934 three of the P.W.A.P's most ambitious projects were unveiled. Charles Kassler's 80-foot fresco celebrating "Spanish California" at Fullerton Jr. College, the Astronomers Monument, and Lafayette Fountain all garnered good reviews, though the Astronomers Monument was considered rushed. A few months later Buckley MacGurrin's fanciful "History of Gastronomy" mural was unveiled in the cafeteria of the L.A. Museum.

All in all, the P.W.A.P. had employed 3,709 artists nationally. Looking back on the excitement of the project, Arthur Miller exclaimed:

"The program cost the treasury $1,312,177.93. The stimulus to American art and its appreciation is incalculable."6

The "American" Scene

All this gooey goodness could not last forever. Effective criticism must indeed be dispassionate, and in January of 1935 at the Ebell Club Salon, Arthur Miller finally gave Ada May her fist poor review:

Miss Sharpless's immense "Queen of the Angels." is the [shows] centerpiece. It is not her happiest work. Simplicity on such a scale demands a compensating subtlety which is absent. -- Los Angeles Times, January 13, 1935

Revealing perhaps a prickly or prideful character, or simply defending herself against a feud or vendetta lost to time, Ada fought back. She wrote the L.A. Times a scathing letter, condemning her old supporter Miller, which according to Miller was "unfortunately too long to publish." She believed that his was "superficial and destructive criticism. [Queen of the Angels] is one of the best pieces of work I had done so far."7 She added that "several people of the most sophisticated artistic taste in the city" agreed with her. Hinting at a secret agenda, she went on, "forget what is being represented. This has nothing to do with whether the sculpture is good or not."

This author could not find a good review of Ada May's work written by Miller ever again. Despite his opinion, that year the statue was placed on the Echo Park's peninsula at the head of the lake, standing on a tall pedestal boxed by four bas reliefs featuring the Hollywood Bowl, L.A. harbor, San Gabriel Mountains, and the Central Library. It joined a new boathouse funded by the Public Works Administration, and was quickly a hit with locals.

Good news also came from the Federal Government. Due to the success of P.W.A.P., the more selective and long lasting Federal Arts Project (1935-1943) was formed under the umbrella of the Works Progress Administration, as were several other government supported arts programs. These programs would eventually nurture future American superstars Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Walker Evans, and Orson Welles, and help create the truly American genre of abstract expressionism. Stretching to today, P.W.A.P.'s brief success can be seen as the big bang that led to today's National Endowment for the Arts and other similar state sponsored programs.

Ada May continued her work, making "bizarre" masks for community theaters, winning first prize for her sculpted portrait of bandleader and notorious cad, Artie Shaw, at the 1941 Ebell Club Awards. By 1943 she was working for the new dominant force in American commerce -- the military industrial complex. Along with 150 other Southern California artists, including noted sculptor and fellow P.W.A.P participant, Henry Lion, she made detailed illustrations for catalogues produced by Douglas Aircrafts for their wartime planes.

Over the years the art of the P.W.A.P was deemed by many to be amateurish, outdated, and "commie." As early as 1939, the Fullerton School Board decided to whitewash over Charles Kassler's "Spanish California," considering it too depressing. MacDonald-Wright's Santa Monica Library murals were put into storage in the 1960s, mostly hidden from the public until the library re-installed them in 2005.

The "Lady of the Lake" suffered a similar fate. Long neglected, fingers broken, and covered in graffiti in crime-blighted Echo Park, she was put into storage in 1986. She didn't re-appear until 1999, restored and covered in an anti-graffiti sealant. Now she watches over the renaissance of her neighborhood, a testament to Los Angeles' recommitment to public works -- a new, "new deal" perhaps?

Additional Photos By: Yosuke Kitazawa

_____

1 "Young Sculptress Back to Own Clime" Los Angeles Times, August 10, 1929

2 "Paychecks, Not 'Gush,' Give Starving Artists Inspiration" Los Angeles Times, February 4, 1934

3 "Art Club Show Below Par" Los Angeles Times, Novermber 16, 1930

4 "Villains, Comedians and Pure Heroes Play Part in Federal Art Project" Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1934

5"Paychecks, Not 'Gush,' Give Starving Artists Inspiration" Los Angeles Times, February 4, 1934

6 "Brushstrokes" Los Angeles Times, November 11, 1934

7 "Brushstrokes: Sculptor Objects" Los Angeles Times, January 27, 1935