Memories of El Monte: Art Laboe's Charmed Life On Air

In Partnership with the South El Monte Arts Posse

"East of East" is a series of original essays about people, things, and places in South El Monte and El Monte. The material traces the arrival and departures of ethnic groups, the rise and decline of political movements, the creation of youth cultures, and the use and manipulation of the built environment. These essays challenge us to think about the place of SEM/EM in the history of Los Angeles, California, and Mexico.

Oldies stations are one of the most tried and true formats on the FM radio dial, seemingly ubiquitous if often absorbed subconsciously. Whether heard in the produce aisle at the local supermarket, planting an earworm for days, or while driving on the interstate through an unfamiliar city, "great hits of the '50s, '60s, '70s, etc." can reliably be found - or find you.

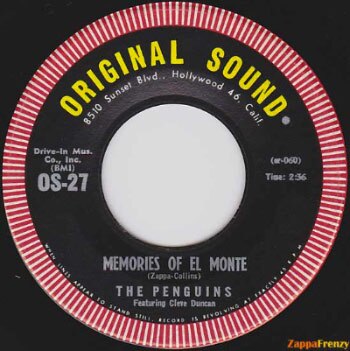

Depending on the depth of a station's playlist, a warm, nostalgic doo-wop track by the Penguins (featuring Cleve Duncan) might float past. Over the same stately chords as the Penguins' best-known hit, "Earth Angel," Duncan sings of lost love and happier times: "I'm all alone,/ Feeling so blue,/ Thinking about you,/ And the love we once knew;/And each time I do,/ It brings back those memories,/of El Monte." What in the fleeting 2:46 of a 45rpm vinyl record seems like standard sentimental Oldies fare, however, turns out on closer inspection to be a fascinating artifact and reminder of the interethnic promise that early rock n' roll held for the youth of Southern California.

Curiously enough, "Memories of El Monte" was penned by Frank Zappa, later a major figure in 1970s progressive rock with his band the Mothers of Invention, and arguably one of the most innovative composers of the American avant-garde. The doo-wop track for the Penguins was one of the first songs that Zappa wrote, and reflects his adolescence steeped in the fertile rhythm & blues scene of the greater Los Angeles area. When Zappa wrote the song in 1962 with friend (and future Mothers singer) Ray Collins, he had been listening to Memories of El Monte, a 1960 re-issue compilation of singles from the mid-'50s heyday of doo-wop put out by Original Sound Records, the independent label of local radio celebrity and concert promoter, Art Laboe. Zappa in turn brought the song to Laboe, who agreed to pay to record and release it as a single on his label. Laboe used his connections to help Zappa recruit the lead vocalist of the Penguins, Cleve Duncan, backed by tenor Walter Saulsberry and the Viceroys, another local doo-wop group, with Zappa on the xylophone.

Ever the shrewd, understated impresario, Laboe asked Zappa to include mentions in the lyrics of classic doo-wop songs that also happened to be tracks on the Original Sound compilation. As a result, the second verse, spoken by Duncan, is a poignant call-and-response recollection of dances past:

If only they'd have those dances again,

I'd know where to find you, and all my old friends.

The Shields would sing..."¨'You cheated. You lied...'

And the Heartbeats... 'You're a thousand miles away...'

And the Medallions with "The Letter" end... 'Sweet words of his mortality...'

Marvin and Johnny with 'Cherry Pie...'

And then, Tony Allen with... 'Night owl...'

And I, Cleve Duncan, along with the Penguins, will sing,

'Earth angel, Earth Angel, Will you be mine?'

At El Monte.

The resulting single is at one level a curious postmodern pastiche of the doo-wop genre, not out of place with Zappa's later affectionate parodies and homages to American popular music genres. But the central role that Laboe played in its making as well as the evocation of El Monte tap into a deep reservoir within the cultural history of Southern California, and in particular the Chicano community.

Beginning with dances he threw at El Monte Legion Stadium in 1955, through a half century as a beloved Oldies DJ connecting with his audience on a nightly basis, Art Laboe has become an iconic voice for Californians who do not fit the glamorous conception many Americans hold of L.A. As author Susan Straight lyrically suggests, these are the people "cruising, boxing groceries, welding mufflers, changing tires, sewing prom dresses, picking oranges, teaching kids," and calling Laboe every night to dedicate songs to their loved ones.

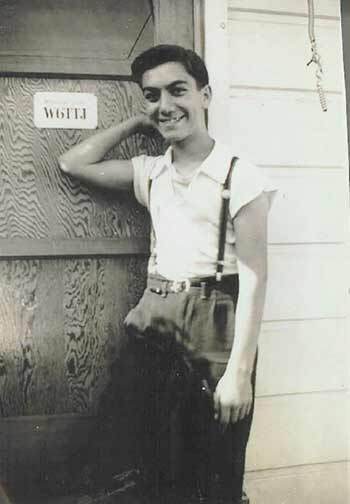

By his own telling, Art Laboe grew up with the medium of radio broadcasting. He was born Art Egnoian to immigrant parents of Armenian descent in Salt Lake City, Utah on August 7, 1925, three years after Marconi first began regular wireless radio broadcasts of entertainment programming. From an early age, he remembers being "completely enthralled by the box that talked," a fascination that became a hobby and then a profession when he moved to Los Angeles in 1934 to live with his sister after his parents divorced. As a teenager, Laboe became involved in ham radio circles and even started a station out of his bedroom in 1938. As Laboe related the story in an interview with Josh Kun, it was during his service in the Navy Reserve during World War II that he received his first break in commercial broadcasting.

While stationed on Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay in 1943, the young Art Egnoian showed up one day at local station KSAN to ask for airtime. Despite his inexperience, he was able to secure a one-hour time slot - 11pm to midnight - because of a shortage of license-holding DJs due to the war; crucially he had acquired the relevant broadcast licenses during a brief stay at Stanford to study Radio Engineering. The station manager at KSAN suggested that Egnoian change his name, so Art took the last name of a secretary working there, "Laboe." From his first program at KSAN, Laboe stumbled upon the technique that has become the signature of his broadcasting style: the personal dedication. In 1943, there were few records played on radio, which then focused on news, information, and live theatrical and musical performances. When there was airtime to fill, a station would play records, mostly of big bands and pop vocalists, the task that fell to Laboe in his time slot. He quickly discovered that a prime segment of his audience were young women who would call in to dedicate songs to husbands, boyfriends, and brothers in the military.

For Laboe, then as now, the personal dedication was a tangible form of connection between the DJ, alone with his microphone in his studio, and the invisible audience receiving his broadcast. But it also has helped to gain the loyalty and personal investment of listeners. When a listener calls to dedicate a song to a loved one, Laboe serves as an intermediary between his listeners, connecting two points across space, while offering recognition by his voice for a personal emotion or experience. Throughout his career, the dedication has been fundamental to Laboe's approach. Bridging the distance of military service has been extended to other absences - for loved ones in prison, or those travelling for migrant labor, or even just the lonely worker on the graveyard shift.

Laboe's focus on taking requests also helped him - again fortuitously - to anticipate the groundswell of rock n' roll within postwar teen culture in the mid-1950s. After the war, Laboe had a difficult time finding work when more experienced DJs returned from the service. He bounced around stations east of Los Angeles in Palm Springs and the Pomona Valley before trying a mobile DJ booth for KPOP in L.A. His most popular remote location, and one that he would occupy for eight years from 1951 to 1959, was in the parking lot of Scrivener's Drive-In at the corner of Sunset and Cahuenga in Hollywood.

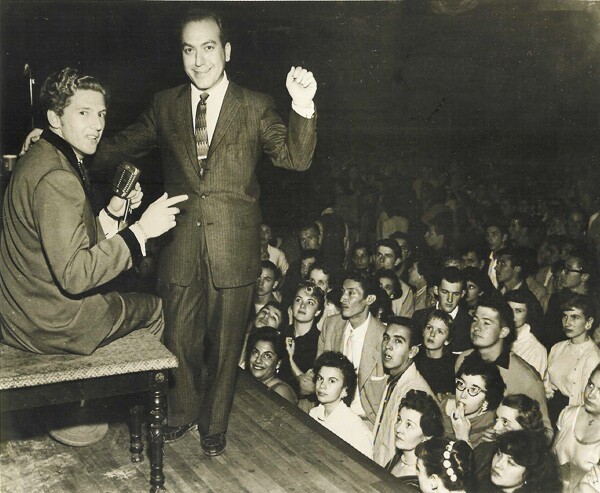

Only a few blocks from Hollywood High, Scrivener's was the epicenter of L.A.'s effervescent teen culture, which combined automobiles, mass culture, and discretionary income to set the standard for youth nationwide of a new mode of freedom through consumption. Laboe began at Scrivener's doing a late show until 4 am, broadcasting to cruising teens throughout the region. He eventually added an after-school broadcast at 3 pm - what he called "record hops" - taking song recommendations from the kids he interviewed. When the national craze surrounding the first rock n' roll hits of Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Little Richard reached L.A. in late 1955, Art Laboe became the first DJ to play these singles on the West Coast, largely based on tips from his teen informants at Scrivener's. While continuing to play the doo-wop and R&B records that had been the staple of his broadcasts until then, Laboe achieved local celebrity because of rock n' roll, as his show became the highest-rated on L.A. radio and served as a promotional destination for this new brand of pop stardom.

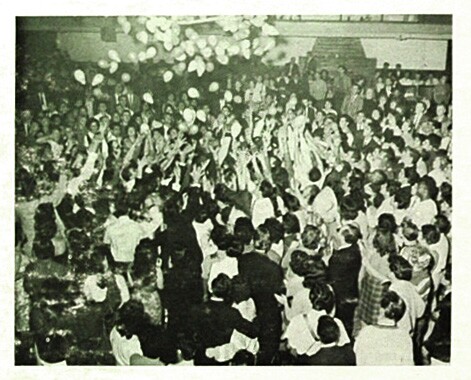

The runaway popularity of the Scrivener's broadcasts created traffic jams around the drive-in, convincing Laboe to organize "dances & shows" for his radio audience. This led him to El Monte Legion Stadium, a non-descript, somewhat rundown boxy auditorium with a 3000-person capacity, which had been built as a wrestling venue for the 1932 Olympics and later hosted boxing, professional wrestling, roller derby, and jamborees. Laboe came to El Monte because regulations in the city of Los Angeles did not allow public dances for patrons under 18, who formed the core of Laboe's audience. Starting in 1955, Laboe hosted an event on every other weekend at Legion Stadium, drawing enthusiastic teenagers from all over the region. The events alternated dancing to records with live performances, both by local artists such as rockabilly duo Don & Dewey and Rosie & the Originals, and rising stars that included Jackie Wilson, Sam Cooke, and Ritchie Valens, the Latino heartthrob tragically killed in a plane crash in 1959.

Laboe cemented a bond with his audience by going into the crowd to meet people. He would talk with groups of teens and ask them about themselves and their favorite songs, as he had done at Scrivener's. Laboe also visited those waiting in line outside to get into the venue. Shows at Legion Stadium typically cost $3, but when a big name-act such as Jerry Lee Lewis or Jackie Wilson appeared, the cover went up to $3.50, leaving some concertgoers short of the extra 50 cents. As Laboe tells it in an interview for the SEMAP archive, "I remember filling both my coat pockets with half dollars - there were a lot of half dollars around then - and I went outside where everybody was waiting in line and went up and down the line and I could see who was trying to dig up some money - people were real honest about it - and I was handing out these half dollars to some of these kids." When the promoter chastised him for leaving the stage and giving away money before the show, Laboe replied that's how he wanted to do it, allowing everyone the chance to get into the show.

For the six years that Laboe put on shows in El Monte, he provided a venue for a spontaneous community of youth that cut across ethnic, racial, and class lines. While the shows drew the more affluent fans from the Westside who had made up the Scrivener's crowd, the core audience for the events was drawn from the local Mexican-American enclaves in East L.A., the San Gabriel Valley, and El Monte as well as black and white working-class neighborhoods south and east. As historian Matt Garcia has described, radios and automobiles helped facilitate an informal network across Los Angeles, united by Laboe's personality and love of the music, that converged at Legion Stadium for an intercultural exchange remarkably free of the racial tensions within social spaces that characterized their parents' generation. Laboe remembers that the events were meant to be "fun, fun, fun," and the atmosphere encouraged non-conformist fashion (due to lack of a dress code), self-expression, and a general good will that seems almost utopian in retrospect. And memories of El Monte Legion Stadium - only the recent past when Zappa wrote his single - have made a strong impression to this day on Laboe, the performers, and the youthful audience who went there. It remains an open question for further research whether the harmonious atmosphere that Laboe and others remember reflects a nostalgic veneer or a genuine collective spirit that tolerated and perhaps encouraged interethnic mixing, dancing, and dating in an era when crossing such boundaries was deeply fraught.

As with many such conjunctures in American popular music, an incipient moment of promise proved to be fleeting, as the emerging record industry in Los Angeles absorbed, elaborated, and transformed the energy of early rock n' roll into a more predictable and manageable product. The El Monte shows had inspired a wave of local bands who enjoyed success as live performers in dancehalls across the Eastside, but these groups were increasingly overshadowed in the '60s and '70s by the popularity of national acts on the radio. One group that emerged from the late '50s scene to achieve national success, and kept alive its multiethnic spirit, was War, whose 1975 hit, "Low Rider," captures (if in caricature) one of the central elements of a night out in El Monte. By the time Legion Stadium was torn down in 1974 to make way for a post office, the concerts there had truly passed into memory even as the music of that time persisted on the radio with the emergence of Oldies stations.

Art Laboe's brand of nostalgia has never been rueful, however, and his career over the last four decades reflects the optimism and resilience that characterized his personality from the beginning. Laboe arguably invented Oldies as a format, coining the term on a series of compilations on Original Sound titled Oldies But Goodies, Volumes 1-15. According to Laboe, he came up with the concept at Scrivener's Drive-In to refer to tracks only three or four years old that his audience would still request. The key point, in his words, is that "it's old but it's gotta be good," which still serves as a core principle of his radio shows today. Laboe has also maintained longstanding "familial" relationships with several performers who appeared at El Monte, including the Penguins and Rosie Hamlin of Rosie & the Originals, acts whom Laboe continues to play on his show and presents at Oldies concerts in the L.A. area.

Through the many transformations of radio, from AM to FM to cable and into the era of Clear Channel, Laboe has always leveraged his popularity to retain full autonomy in the presentation of his show. As of 2013, Laboe appears 31 hours over 6 nights a week on Killer Oldies and Art Laboe Connection, and remains a Top 5 draw nationally in the ratings. In an era when many Oldies stations are automated, sticking to a limited, market-tested playlist without DJs, Laboe draws on his own deep knowledge of popular music and the musical affections of his listeners to intersperse perennial hits with singles more obscure to a younger audience. Nevertheless, he remains popular across a wide range of age groups, and proudly takes dedications from ten-year-olds as well as abuelas. As Laboe slyly notes, he puts people on the air "from womb to tomb."

It is this intergenerational appeal, built off his affable stewardship of the El Monte "dances & shows," that has made Laboe an honorary voice of the Mexican-American community in Southern California, his radio program providing a soundtrack of Chicano identity. State Senator Gil Cedillo vividly recalls cruising through Boyle Heights in the early '70s with Antonio Villaraigosa in the future mayor's canary yellow 1964 Chevy listening to Laboe, whom he likened to "everyone's favorite uncle in the neighborhood." Comedian Paul Rodriguez told the L.A. Times that Laboe "is more Chicano than some Chicanos, and everyone from the toughest vato to the wimpiest guy would say the same." Yet Laboe's reputation remains strong even among younger Mexican-Americans today, such as a 21-year-old student who told Susan Straight, "Art Laboe! Man, I grew up in Baldwin Park and the whole neighborhood listens to him! The women love him."

Laboe typically demurs at such suggestions, however, and one has the sense that he is a universalist in his sense of the origin and appeal of Oldies: everyone chipped in over the years to make great music and have a good time. In the shark tank that commercial radio and the record industry can often be, Laboe's serene, unassuming approach throughout his career is remarkably rare. But his longevity makes complete sense in that he seems to have a wise understanding of the meaning that the music has for his listeners - in their memories and their relationships - and he makes himself the conduit for that. If Art Laboe has led a charmed life in radio, he has shared it with many.

This piece was originally published on Tropics of Meta in January 2014.