California Summer, Baby, is Getting Out of Hand: The Diggers and the Summer of '67

June gloom days typically make Los Angelenos eager for the warm sunny days of Southland summers, but in June of 1967 those hip enough to be in the know were looking with worrisome eyes toward the summer months, anticipating the predicted invasion of 100,000 or more hippies to Los Angeles, its beach communities, and even into staid Orange County. 1

While Los Angeles cops and straights might have only demonstrated a mild concern with this rumored mass migration, it was the Los Angeles Diggers Creative Society who expressed the most apprehension and concern about the love children's imminent arrival. The San Francisco Diggers, shivering away in the foggy panhandle of Golden Gate Park, had too been anticipating the projected influx. Each group asked themselves: What would the hippies eat? Where would they crash? Who would give them jobs? And how could they avoid getting busted by cops?

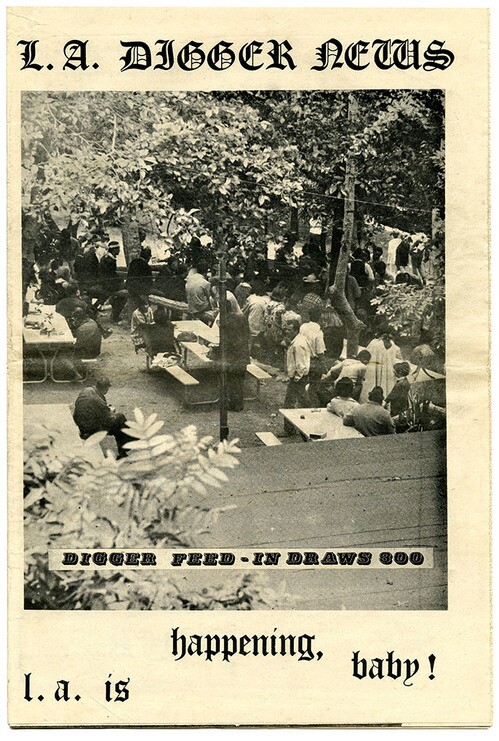

L.A. Digger News, the first published newspaper of the Digger Creative Society -- undated but circulated in the late spring or early summer of 1967 -- addressed the questions that were on the minds of L.A. Diggers. This bygone newspaper, or more aptly, countercultural rag, was found in a box of unsorted materials -- handbills, flyers, pamphlets, self-published magazines -- awaiting processing by myself, an archivist at the California Historical Society. The newspapers published by the L.A. Diggers fascinated me. I had never heard of a contingent of Diggers in Los Angeles, although I had been familiar with the San Francisco Diggers, a rowdy and rebellious counterculture group firmly rooted in the Haight Ashbury scene, whose theatrical, political actions became part of the cultural fabric of hippie-era San Francisco. But of their Southland brethren I knew nothing, and their newspaper provided little information about their inception. A web search produced only two other pieces of ephemera, both flyers for benefits organized by the Diggers. Were the Los Angeles Diggers an offshoot of the San Francisco group? How were they alike, or were they even alike at all?

The San Francisco Diggers, most certainly, were the originators -- that is, at least, by 20th century standards. The S.F. Diggers grew out of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, a satirical, rambunctious, political theater group that had included S.F. Diggers originals Emmett Grogan, Peter Berg, and Peter Coyote. The S.F. Diggers took their name and philosophy from a 17th century English agrarian-communist community founded by Gerrard Winstanley and William Everand, who led their band of farmers to plots of fallow, common land at St. George Hill in Surrey, England, and encouraged them to dig, sow seeds, and cultivate land that, in their view, rightfully belonged to those who were hungry. The English Diggers believed that property was "the cause of all war, bloodshed, theft, and enslaving laws that [held] people under miserie [sic]", they refused to participate in the buying or selling of any goods, services, or ideas, and "weren't satisfied to disobey authority civilly; they literally ignored it." 2 As could be expected, their movement didn't last long -- beginning in 1649 and culminating with the harassment and incarceration of group members in 1650.

Although short-lived, their movement influenced their San Francisco progenies greatly. Firstly, 17th century Diggers' implementation of direct action -- based on the simple logic that one sees uncultivated land and cultivates it, no permission asked, not even considered needed -- can be boiled down to the 20th century Diggers' simple, straightforward mantra, "Do it, baby." Hippies hungry in the Haight? Find free food, cook it up in a huge pot, and give it away in the Panhandle. Second, the S.F. Diggers too, paid little heed to any sort of civil authority. Their first rally took place on October 6, 1966 (handbills pointed out the devilishness of the date); the same day the State of California criminalized the possession of LSD. Diggers, along with publishers of the Oracle, a Haight Ashbury underground newspaper, organized an afternoon gathering of people at Masonic and Oak streets. To the crowd the Diggers read their reimagining of the Declaration of Independence, wherein the inalienable rights of humans include freedom of the body, the pursuit of joy, and the expansion of consciousness. Embodying the Diggers ethos to "do it," hundreds of hippies and heads dropped acid at the same moment, a communal action declaring their independence of, and indifference to the straight world's laws and moral code.

The San Francisco Diggers had made their mark on the counterculture community, while at the same time attempting to differentiate themselves from the hippies who they believed were just "white kids who weren't that hip." 3 Most of the S.F. Diggers were nearly a decade older than the love children, whom S.F. Diggers considered merely innocents dropping into the deceptively peaceful Haight-Ashbury scene. The Diggers wanted to "infuse the new culture with their ethos," which celebrated taking advantage of the surplus of the middle and upper classes and making it available to those in need. 4 They created a Free City, where those who needed it had access to free food which had been gathered by the Diggers from the grocers and produce markets of San Francisco and cooked in their own kitchens; a Free Store, which took donations of clothing and other goods and gave them away to those in need; and the Free Medical Clinic, which provided free advice and services, typically to those suffering from sexually transmitted diseases and/or side effects from bad drug experiences. As the population of the Haight began to grow, the ability to provide free goods and services became much more difficult, especially as the San Francisco Police Department began to shut down the Free Store as it moved from one location to another around the neighborhood. Additionally, as is can be expected when "innocents" congregate to a locale, there was no shortage of shady characters willing to prey on the naiveté of the newcomers. The S.F. Diggers could foresee that something systemic was going to have to be done to address the welfare of the hippies, as more and more of them migrated into the Haight as summer drew near.

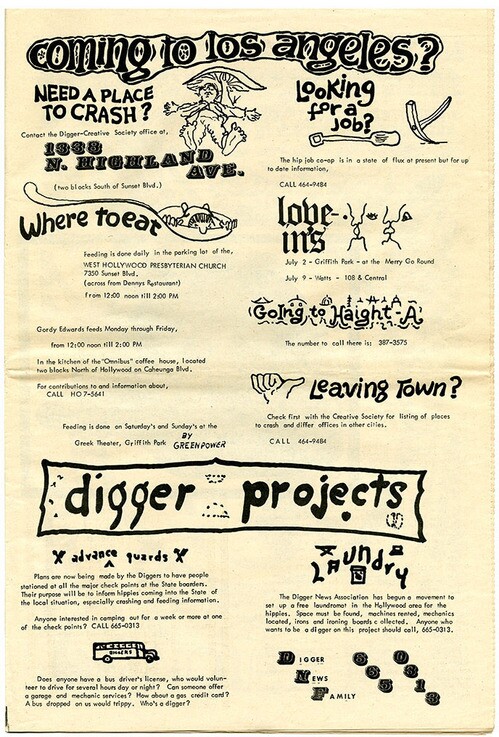

The Los Angeles Diggers, too, began to develop strategies to deal with the growing Southland hippie community. The L.A. Diggers provided a variety of outreach services similar to those offered by the S.F. Diggers, and their generally we-can-handle-it tone and demeanor towards the projected inundation of 100,000 hippies seemed to hinge on their earnest belief that the hippie community would bond together to take care of each other. The early Spring/Summer 1967 issue of L.A. Digger News, published by Digger Creative Society members Plastic Man and George at their home base location at 1338 Highland Avenue, contained numerous articles about how hippies, cops, straights, and the Digger Creative Society (DCS) might handle the mass human inflow. They consulted Don Strachan, who they considered to have "a fairly accurate reading of the community pulse" as the associate editor of the L.A. Free Press. 5 The DCS reported that although Strachan was impressed by their own efforts to prepare for the influx, the establishment was too inflexible and could only approach the situation "within its own structure and thought patterns," predicting "a big game of cops and robbers" where "police will be busting everywhere" and "jails will be full." Strachan also credited Los Angeles for its growing hippie scene, but worried "there [were] not enough hippies yet to absorb the projected influx this summer." 6

The efforts Strachan acknowledged on behalf of the DCS were impressive. Both issues of their newspaper included articles detailing their outreach efforts, along with a variety of services planned as the summer months approached and the hippie population grew. The DCS could offer sleeping facilities in private homes around the L.A. area for up to 200 hippies; they provided food at 7351 Sunset Boulevard (across the street from the famous "Rock 'n' Roll Dennys") every day at 2 p.m. and at all major love-ins, and encouraged other attendees to "BE A DIGGER: BRING EXTRA FOOD: DO IT BABY!"; the newspaper published information about where to access free health care such as vaccinations for babies and children; they operated a Free Store in South Central Los Angeles at 4108 South Central Avenue; and they raised money throwing $1.00 a head dance benefits on Sunday nights at King Banjos at 7551 Sunset Boulevard and at the Psychedelic Temple located at 1039 South Ardmore on Friday nights, were they supplied "three bands, a light show and good vibrations." Other benefits included a Valentine Day event and a Friday the 13th celebration that included a performance by comedian Richard Pryor. The DCS also had aspirations to set up a free laundromat in the Hollywood area; to offer workshops on "sewing, sandal-making, and even auto mechanics"; to encourage talk-ins between the "Cadillacs" (straight establishment) and the "long-hairs" (hippies); to establish a "hip job co-op" where employers who were willing to hire hippies could find hippies that were willing to work; finally, and most curiously, the DCS intended to hire (at subsistence wages) people who would be willing to "rough it" at all major check points at the California state border and provide incoming hippies with information about where to crash and feed.

Clearly the L.A. Diggers had an idealistic, ardent approach to how they could help the hippies heading to the City of Angels, but their concern and solutions, no matter how impractical, seem genuine because they themselves identified as hippies. On the contrary, the S.F. Diggers felt the need to help the hippies in the Haight because they were older and wiser and had an ethos to impart on the naive hoards, never taking the label of "hippies" for themselves. Beyond just self-identification with the hippie movement, the two groups demonstrate differences in how they conducted themselves and their social agendas. The editorial policy published in the L.A. Digger's second newspaper, now called the Digger News Association, exposed some of the crucial differences in the groups. In acknowledging the paper's name change, the L.A. Diggers warned their readers that the name of the paper would change with each new issue, stating, "Worry about identity? continuity? Not us." 7

There is also some bleariness about the distinction between the L.A. Diggers and the Diggers Creative Society, which is never sorted out in the two newspaper publications I have seen. The S.F. Diggers were true to their organization's name and identity, only abandoning their name entirely when Digger associate Billy Jahrmarkt named his son Digger. Henceforth they were known as the Free City Collective. Secondly, the L.A. Diggers editorial policy solicited financial donations from "people who [dug] the hippie scene" and who were willing to contribute "to any and all of the hair-brained activities Diggers might come up with." The paper also promoted Digger benefits where financial contributions were collected. The S.F. Diggers famously rejected financial contributions -- Grogan once lit fire to a cash donation made by Paul Krassner, editor of underground publication the Realist and refused the check of a San Francisco socialite, requesting she donate clothing instead.

Though the S.F. Diggers might come off like dogmatic, naysayers whose approach to the hippie influx seemed a sort of off-kilter, psychedelic brand of paternalism, their concern for the newcomers was justified. Within the San Francisco hippie community it was not only the cops to watch out for. Haight Street merchants looked to the hippie masses descending upon the neighborhood as a means to increase their profits. Haight Independent Proprietors (HIP), a loose organization of Haight Ashbury merchants, had sponsored the January 1967 Human Be-In, which garnered national media attention and influenced the mass migration of hippies to the neighborhood. Grogan argued that because HIP was partially responsible for the influx they had a responsibility toward the welfare of the newcomers. Not impressed by the merchants idea of a job co-op, wherein jobless hippies worked in sweatshop conditions to embroider clothing that was marketed back to the hippies, Grogan exploded at the merchants, calling them "cloud-dwellers" and worse, effectively cutting off any chance of HIP and the Diggers working together.

As summer loomed, the S.F. Diggers had to contend with more propaganda encouraging youth to descend on San Francisco. In May of 1967 singer Scott McKenzie released the hit song "San Francisco." Written by L.A. music producer Lou Adler and John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas to promote their Monterey International Pop Music Festival to be held in June of 1967, the song encouraged those converging upon the city to "wear a flower in [their] hair." The S.F. Diggers responded with a broadside ridiculing Adler and Phillips' lyrics, and likening the San Francisco scene to dismal, riotous ghettos. The S.F. Diggers further needled Adler and Phillips when they held a solstice celebration "Do-in" three days after the Monterey International Pop Festival with the Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and Big Brother and the Holding Company, using Fender speakers and amplifiers "liberated" from Monterey Pop musicians.

Some of the 50,000 or more who arrived in the Haight were college students on summer breaks wanting to get a taste of the counter-culture "utopia" before heading back to class in the fall, but many were already difficult cases -- runaways looking for free food and a place to crash, and drug addicts looking for a cheap and steady supply. By the beginning of August, the Haight was overcrowded with needy, desperate hippies and addicts. The S.F. Diggers simply could not address all of their welfare concerns. Predators swooped in to take advantage of the most dis-spirited and naive. Rates of sexually transmitted diseases, mental health issues, and drug addiction -- including addiction to methedrine -- grew, and the Haight quickly deteriorated into a dark and dangerous scene. Rape was not uncommon, and typically went unreported. The summer culminated with the mysterious murders of two known drug dealers. Certainly, "the whole summer was turning out to be an epic bummer." 8

The L.A. Diggers summer of 1967 was much less macabre. With the exception of warnings about heavy-handed, prejudiced cops who might be quick to bust a hippie, the L.A. Diggers newspapers did not indicate that the hippie influx had created any sort of critical situation for the community. Despite Los Angeles being a major urban area where crime was prevalent and drugs accessible, the Summer of Love in the city seemed to come off without any significant measure of trouble, lacking the somber and downright scary vibes of San Francisco's summer as it drew to a close. Film footage located on YouTube of love-ins in Griffith Park depicts smoky, sunshiny days full of love, music and dancing. Contrary to what Don Strachan had observed in the columns of the L.A. Diggers newspaper, it seemed that Los Angeles' hippie community was strong enough to absorb the influx, perhaps the L.A. Diggers' outreach was effective.

It is impossible to quantify how many hippies actually made their way to Los Angeles, but the L.A. Diggers prediction of 100,000 was certainly inflated. In comparison, San Francisco's projected intake of hippies was 50,000, and the city had certainly been better marketed, even if unintentionally, with the Human Be-In and the Scott McKenzie's hit record. The less than projected number of hippies arriving in Los Angeles undoubtedly worked in favor for the L.A. Diggers and their efforts to keep hippies fed, clothed and housed. Certainly, a Fall issue of their newspaper might have summarized their success over the summer, but I am unaware of the existence of any such publication. Unfortunately, how effective the L.A. Diggers outreach towards the hippies was through the summer of 1967 and what became of their organization after summer came to a close remains unknown. Los Angeles' summer of 1969, when Charles Manson persuaded his followers to murder nine people in late July and early August, has clearly overshadowed the city's Summer of Love and the contributions of the L.A. Diggers, and is typically blamed for the death of the peace and love movement. But for that Summer of 1967, it seems Los Angeles had it pretty together.

If anyone has more information about the Los Angeles Diggers Creative Society and their publications please feel free to email me at jhenderson@calhist.org.

_____

1 "Summer Forecast," L.A. Digger News, Spring/Summer, 1967.

2 Gitlin, Todd. The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. (New York: Bantam Books, 1987), 224.

3 Ibid., 223.

4 Ibid.

5 "Summer Forecast," L.A. Digger News, Spring/Summer, 1967.

6 Ibid.

7 "Where are we now?," Digger News Association, Spring/Summer, 1967.

8 Hjortsberg, William. Jubilee Hitchhiker: the Life and Times of Richard Brautigan. (Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2012), 321-322.