A Giant in a Forest of Green: Robert García, A Leader in L.A.’s Environmental Justice Movement Passes Away

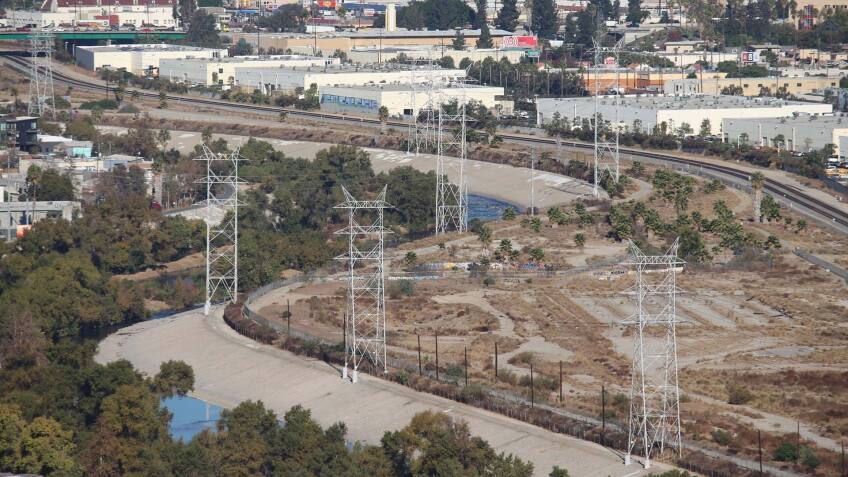

Two things have shaped the life of Robert García. That he was a civil rights attorney and that he was an immigrant. The Founding Director and Counsel of The City Project, a non-profit legal and policy advocacy team in Los Angeles, García, a KCET Local Hero in 2013, has touched the lives of millions. Every step Angelenos take at the green, open spaces such as the Los Angeles State Historic Park (better known as the Cornfield), Baldwin Hills Park, Taylor Yard or the San Gabriels, America’s 110th National Monument, is partially thanks to his tireless advocacy.

“Many of us in the region were beneficiaries of his work without even knowing it,” says David McNeill, Executive Officer of Baldwin Hills Conservancy, who witnessed García’s tireless advocacy for clean air in his neighborhood of Baldwin Hills. “He stood arm in arm with Black and Brown people and helped us win the battle against the creation of a fast-tracked Peaker Power Plant in the heart of the future Parklands.” It would be just one of his many accomplishments throughout the region.

García passed away April 6, from cancer at the age of 67. His wife, Susan Allison; his three sons Nicolas, Tomas and Samuel; his sister, Lucrecia; and his mother, Ana Maria, survive him.

“Robert didn’t do anything half-heartedly,” said Allison of her husband. “He was a great thinker, and so he brought a lot of energy and intelligence to all the jobs he did” — much of it to Los Angeles’ benefit and especially the city’s under-served communities.

“Robert García helped us to recognize the importance of parks and open space for human development and who showed us the discrepancies in investment, especially for communities of color, that really made his work essential,” said Will Wright, the Director of Government & Public Affairs at the American Institute of Architects’ Los Angeles Chapter.

Hear García talk about the importance of green space in urban environments to give children exposure to nature even in inner city living.

About two decades ago, long before anyone had thought of the terms data visualization, García was already working on doing geographic analysis of equity in terms of parks in communities across the Los Angeles metropolitan area. “He was doing these heat maps and saying ‘Look at how few parks there are in this area! Just look!’” recalled Mia Lehrer, President of landscape architecture firm, Studio-MLA. Lehrer and García bonded over their shared Central American immigrant backgrounds. She from El Salvador, and he from Guatemala. García moved to the U.S. at the age of four.

Not only did García recognize the inequities and helped others see it as well, his Stanford law training also enabled him to frame access to green, open space in compelling terms, in the vein of the Civil Rights Movement. “What do things like soccer and obesity and buses have to do with civil rights? Plenty,” García wrote in 2012 for KCET. “Today, a person's health is determined more by where they live, the color of their skin, and how much money they make than by individual behavior, or the amount of money spent on health care.”

Standing on the shoulders of his hero former Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, García fought for the rights of all people, no matter the color of their skin, to live happy, healthy lives in green, open space.

García began his law career at Donovan and Leisure and served as an Assistant United States Attorney in the Southern District of New York under John Martin and Rudy Giuliani.

After moving to Los Angeles in 1987, he moved to Los Angeles, where he taught at the UCLA Law School. He left teaching to pursue work with the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. While working there, he and a team that included Stuart Hanlon and Johnnie Cochran helped set free Geronimo Pratt, the former Black Panther leader, who served 27 years in prison in California for a murder he did not commit.

But it was truly with The City Project that his attentions were focused on the intersection of environmental justice and civil rights. He founded, The City Project, a public interest law firm focusing on environmental justice, in 2000. “[We wanted] to find alternative ways to seek social change through law, without resorting to litigation as the first or only means, in the face of an increasingly conservative Court, Congress, and country.” He wrote in 2014 for KCET.

Fiercely independent, he worked not for others, but alongside others in bringing justice for all communities. “He was one of those guys who did it his way,” said Allison, “He probably couldn’t have worked for anybody but himself, and he worked for himself extremely effectively by having these alliances, working together with groups trying to achieve the same goals.”

Contributing to the legal strategy of the Chinatown Yard Alliance and other groups, García turned the city’s future away from depressing rows of warehouses toward greener futures at what is now the Los Angeles State Historic Park. García's civil rights challenge argued that the fight for the Cornfield was part of the historic struggle for low-income people of color in Los Angeles to find livable communities with parks, playgrounds, schools, and recreation. “The day the park opened was a fantastic moment in his life,” said Allison.

“There would be no Los Angeles State Historic Park, Rio de Los Angeles State Park or, for that matter, a meaningful State Park presence in Los Angeles without Robert García,” says Sean Woods, Superintendent for California State Parks in Los Angeles, who has known García for 19 years. “He was a fighter and could be uncompromising in his mission to highlight the vast park inequities in underserved communities of color. He changed the whole conversation around equitable access to State Parks and our Department is a better organization because of him.:

Another milestone was on October 10, 2014, when former President Barack Obama designed the San Gabriel Mountains a National Monument. On that day, the president himself said, "Too many children in L.A. County, especially children of color, don't have access to parks. This is an issue of social justice." The declaration itself was a validation that access to green, open space was a matter of civil justice.

“He played an important role as a voice,” said Lehrer, who recalled the many times she and García worked with each other on projects around Los Angeles.Not only that, “He was a motivator and doer,” adds Lyndon Parker, Chairman of the Board of the City Project. “He buffered those of us who had strong thoughts on social justice. We could not have put it into action without Robert.”

Through his eyes, from his perspectives, those around him learned and were able to collaborate. Among them was longtime Los Angeles river advocate, former City Council member and now Executive Director for River LA, Ed Reyes. “One of the key factors and role he played was really in pushing for access to green recreation,” said Reyes, “The studies he wrote with his team at The City Project was also constant pressure to hold public authorities accountable, to keep constant pressure, to make sure there was follow-through."

Hear García talk about how the City Project works with community groups to create change.

Because of his work, millions of lives have been changed, including that of Jessica Manuela Loya, who grew up in Northeast Los Angeles. "Growing up in a family that didn't have a lot of money, my family and particularly my mom really emphasized community parks as a way to provide community and opportunities to stay engaged." Loya often played in the gymnasium and ballfield of Cypress Park Recreation Center. Even today, she still enjoys the Rio de los Angeles State Park, formerly known as Taylor Yards.

Only years later, while working in Washington D.C. at the White House Council on Environmental Quality, did she meet García. García had come in to meet about the “Every Kid in a Park” federal program. “When I had an opportunity to sit down with him and talk with him, I realized all the work that he had been doing for the last two decades of his life had impacted me and my community especially.”

García began to mentor Loya after she had left the White House and worked for the Hispanic Access Foundation. It had been a relationship that persisted through different time zones in a span of almost four years and eventually led Loya to her current position at the Green Latinos, a non-profit advocacy and professional network organized based in D.C. that work to address national, regional and local environmental, natural resources and conservation issues that significantly affect the health and welfare of the Latinos in the country.

“Robert loved life and loved living and loved loving other people and other communities, and he shared his love widely,” said Loya. He was an avid and self-taught woodworker with his own workshop in the garage of his home. His home is filled with his Shaker-style furnishings. He loved New Orleans music, Latino salsa. “He was an amazing reader,” said Allison. “He read every level of complexity. His City Project office is chockfull of books about the history of Los Angeles, of California, as well as civil rights and environmental law.”

When not fighting for green, open space for all, García could also often be found bicycling and enjoying the space that he worked dearly for on behalf of communities of color. “He would bike almost every week to the ocean,” said Allison. He would often bring along his sons for the ride.

Garcia's passing leaves behind a lasting legacy in the community, especially in the lives of a younger generation like Loya, who in turn, will be one of the many carrying the torch in Garcia’s stead. “One of the biggest lessons I learned from Robert was that we don’t do work around justice and equity because it’s easy, or fast, or for the praise. We do it because it’s a matter of life and death, because it has a generational impact and because it’s the right thing to do.”

Top Image: Taylor Yard | Courtney Cecale