The Troubling History of Sambo’s Pancake House

"No black who was referred to as 'Sambo' ever thought he was being complimented for his cleverness."

— Los Angeles Times, 1977

"The use of the name ‘Sambo’s’ had the effect of notifying black persons that they were unwelcome at Sambo's restaurants because of their race."The Human Rights Commission of Rhode Island, 1981

In 1957, two white men from Southern California were brainstorming a name for their new restaurant. Sam Battistone Sr. was a “short, compact and determined looking” man who had run a diner in downtown Santa Barbara for two decades. Newell Bohnett was a 34-year-old equipment salesman whose father had been the mayor of Santa Barbara. They wanted a name that was catchy, and that would be familiar to the working and middle class families they hoped to cater to. Combining Battistone’s first name with the first two letters of Bohnett’s last name, they christened their new establishment Sambo’s.

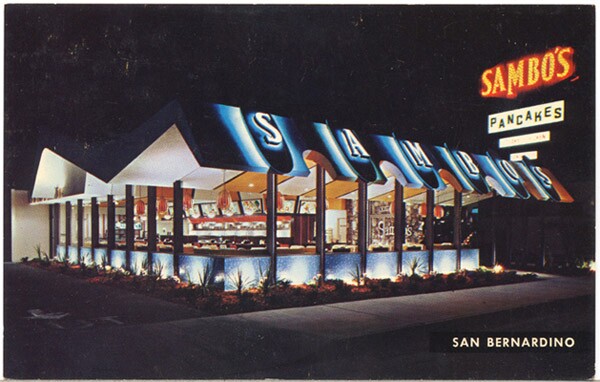

The first Sambo’s Pancake House opened on June 17, 1957 on beachfront Cabrillo Boulevard in downtown Santa Barbara. True to their rather clunky slogan, “What this country needs is a good 10-cent cup of coffee,” the restaurant offered bottomless, inexpensive cups of joe. A full breakfast was only $1.25. Sambo’s soon began attracting a large number of customers, particularly at breakfast. From the beginning, Battistone and Bohnett worked hard to foster a familial feeling at Sambo’s from the clientele to the employees. According to Charles Bernstein, author of "Sambo’s: Only a Fraction of the Action":

Sambo’s initial summer days in 1957 were especially exciting. Early each morning Sam Sr., with his sleeves rolled up, would be busy cooking at one grill while his 17-year-old-just-graduated son was cooking at the other one, and his wife was serving breakfast to whatever customers happened to arrive. The family and Bohnett were counting on an array of twenty-one different pancakes and a few other choice offerings to keep the 45 counter and booth seats reasonably full.

The good vibes also extended between the partners, with Bohnett later recalling, “next to my marriage, my association with Sam Battistone Sr. was one of the most pleasurable and gratifying associations that I have ever experienced.”

The men prided themselves on the warm atmosphere and decoration at their flagship restaurant. Its design was bright and cheerful, there were tantalizing views of the ocean, and the piped-in music was soothing and soft. However, no matter how welcoming the atmosphere, there was a large portion of the population who would never feel “at home” at the restaurant. For on the walls were seven paintings of the story of “Little Black Sambo.” Not to mention, the name Sambo’s itself (unintentionally or not) signaled to people of color that they were not welcome at the restaurant.

By 1957, the name Sambo already had a long and controversial history. Since as far back as the 1500s, the name had been used to denote a black man. By the 19th century, “Sambo” had become an archetypal degrading character in literature and minstrel shows. “Sambo, the typical plantation slave, was docile but irresponsible, loyal but lazy, humble but chronically given to lying and stealing,” historian Stanley Elkins wrote. “His behavior was full of infantile silliness and his talk inflated with childish exaggeration.” Education specialist Jessie Birtha explained that “the end man in the minstrel show, the stupid one who was the butt of all the jokes, was Sambo.”

The paintings that adorned Sambo’s Pancake House were a retelling of the hugely popular children’s book Little Black Sambo. Written by Helen Bannermen, a Scottish woman living in India, it was published in America in 1900. According to author Phyllis J. Yuill, author of "Little Black Sambo: A Closer Look":

[Little Black Sambo] describes a dark-skinned child’s adventures with four tigers … Wearing his new set of brightly colored clothes and carrying an umbrella for a walk in the jungle, Sambo finds that he must give each piece of beloved finery to the tigers to keep from being eaten. Jealous over their new possessions and increasingly enraged, the tigers discard the clothing and chase each other around a tree so ferociously that they turn to melted butter. While Sambo retrieves his garments the butter is salvaged by Sambo’s father, Black Jumbo, and is used to cook pancakes by Sambo’s mother Black Mumbo. They are so delicious that Mumbo has 27, Jumbo consumes 45 and hungry Sambo devours 169.

The book became a runaway hit, its illustrations becoming more caricatured and offensive with each reprinting. Sambo was often portrayed as a “pickaninny” and Black Mumbo as an “Aunt Jemima”. Nominally set in India, the story was often reset in Africa or the American South. It appeared on almost every popular children’s reading list (for both white and black children) through the 1940s, despite the harmful effects it had on children of all races. As one man in Nebraska recounted in the 1960s:

I sat through Little Black Sambo. And since I was the only black face in the room, I became little black Sambo. If my parents had taught me bad names to call the little cracker kids — and I use that term on purpose to try to get a message across to you — you don’t like it. Well, how do you think we feel when an adult is going to take our child … and that adult gives these little white kids bad names to call him?

Beginning in the late 1930s, some educators began voicing objections to the book being used in classrooms. But all this did not stop Sambo’s restaurants meteoric rise. Helped along by a unique system called a “fraction of the action,” which gave location managers a stake in their restaurant’s profits, Sambo’s began to spring up all over the West. By 1965, there were 40 Sambo’s Pancake Houses, serving both Sambo cakes and Tiger butter. At the height of the civil rights movement, the chain embraced its association with Bannerman’s story. Handmade murals, by Colonel and Mrs. Hilmer Nelson, illustrating the tale were part of the décor of every new location. And that wasn’t all. According to Charles Bernstein:

Sambo’s theme was carried through with the tale of Sambo and the tiger stressed in the interior décor and on the menus. Sambo and tiger dolls were sold at each restaurant’s cashier stands, and every child was given a Sambo’s mask upon leaving the restaurant. While Sambo’s would claim that its name was derived strictly from a combination of the two founder’s names, it nevertheless capitalized on the Sambo story.

By 1969, it was said that Sambo’s was serving enough coffee each day “to float a 45-foot-yacht.” Sambo’s restaurants were opening all around the country at a dramatic pace — the chain added 125 new restaurants in 1975 alone. At its peak, Sambo’s would have 1,117 locations in 47 states. But civil rights leaders and town councils began to object to the restaurant with the racially charged name appearing in their town. In the late ‘70s, protests and lawsuits challenging the Sambo’s name were occurring in Virginia, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Ohio and Michigan.

The company responded in a remarkably tone deaf fashion. “There’s no ground for changing it,” Sam Battistone Jr. said in response to calls for a name change from the city of Reston, Virginia, in 1977. “We’ve operated these family restaurants for 20 years on a 24-hour basis, and it’s been Sambo’s the whole 20 years. The name has been accepted across the country.” Bruce Anticouni, Vice President and General Counsel of Sambo’s, agreed. “We are aware of what appears to be the sentiment of a small portion of the people [of Reston],” he said. “Our position is that we have 850 restaurants throughout the country — 845 of them under the name Sambo’s — and the problems you can count on one hand.”

In 1978-79, the growing controversy coincided with the financial collapse of Sambo’s due to managerial and structural problems. Remarkably, even Sambo’s biographer Bernstein sounded an indignant note when describing the chain’s self-inflicted woes at this time:

As if it didn’t have enough troubles, Sambo’s name in New England and some Midwestern states were repeatedly challenged now by NAACP, civil rights groups and indignant consumers. Suddenly people were saying that Sambo’s — once hailed as a great name — was a poor choice. Groups decided they didn’t like the connotation of the name from the children’s story, “Little Black Sambo.” Never mind that Sambo’s hired a much higher percentage of blacks than most other companies and restaurant firms. Never mind that the name was derived from a combination of the two founders — Sam Sr. and Bohnett. Sambo’s was automatically guilty of discrimination in the minds of many, under the thinking of that era.

While judges generally sided with Sambo’s under the banner of the first amendment, the damage in the court of public opinion was done. As one judge said, those who had problems with the chain’s name could “erect signs, carry placards or publish advertisements designed to persuade others to refuse to patronize. That is what freedom of speech is all about.”

And so they did. Sambo’s finally realized the seriousness of the issue and attempted to “start an education process to convince consumers Sambo’s is anything but racist.” They also changed the name of some restaurants in the Northeast and Midwest to “No Place Like Sam’s” and “Jolly Tiger,” but this did little to rehabilitate their tarnished image.

However, it was not protests against the name but financial woes due to company restructuring of the wildly popular “fraction of the action” scheme which led to Sambo’s filing for bankruptcy in 1981. That year 450 Sambo’s closed, and the company lost $50 million dollars. By 1984, all the remaining locations had either been sold or shuttered — except the original beachside Sambo’s in Santa Barbara.

You can still eat at Sambo’s in Santa Barbara, right there on the sparkling beach. Amazingly, you can also still see the seven original paintings, which depict “Sambo” as a kind of cartoon “baby genie.” Battistone heir Chad Stevens, who now runs the restaurant, told reporter Andrew Romano in 2014:

We do get the occasional complaint. They want us to know the controversy of the name. And yet for every complaint, there are about 1,000 people who say, ‘Wow, I can't believe it’s still here’ — or ‘Open another one in our town.’

Today, the banner headline of Sambo’s website reads, “Doing it right, since 1957.”

Top Image: Thomas Hawk/Flickr/Creative Commons License