Infernal Machines: The Bombing of the Los Angeles Times and L.A.'s First 'Crime of the Century'

It never fails to astound me. The tales we remember collectively. And the stories we forget. I first learned of the 1910 bombing of the Los Angeles Times on a walk around Hollywood Forever Cemetery. There, next to graves of the Otises and Chandlers, is a grand monument to "Our martyred men," the 20 employees of the Los Angeles Times who had lost their lives in the early morning hours of Saturday, October 1, 1910. There is a list of the deceased, fourteen of whose remains are buried beneath the monument. They had been hard at work at the Times' headquarters, often called "The Fortress," on the northeast corner of First and Broadway, when a series of dry blasts starting at 1:07 a.m. shook downtown Los Angeles to its foundations.

When I was growing up my father ran a paper and a printing press. I spent many happy nighttime hours at the press -- running in and out of the revolving doors of the dark room and climbing on the great rolls of newspaper. I can still remember the smell of the ink, the clanging rhythm of the insert machine, and the dark ink smudges on the pressmen's shirts. There was a sense of camaraderie among the folks who worked at the paper -- the odd hours, the stress of deadlines, and the constant noise. Perhaps these memories are why this story so resonates with me.

At the current home of The Los Angeles Times on Spring Street, faded and half empty, there are few references to the bombing. There is a brief blurb about it in a historical timeline exhibit in the lobby. There is the cornerstone laid in 1934 by Harry Chandler, which contains a copper box with a list of the dead and other mementos. The words "True Industrial Freedom" are etched into the building's façade, a reference lost to most casual pedestrians.

Across the street is an empty lot where "The Fortress" and its immediate successor had once approximately stood. The day I visit, there is a faint smell of urine and trash, and the detritus of the city clogs the lot's chain link fence. Weathered signs proclaim that the block will soon be a city park, and flowering bushes have already reclaimed much of the area. Stray sheets of newspapers blow through high, rustling weeds. The ruins of a later government building are visible, and a desk and chair sit on ghostly guard at the top of a set of stairs overgrown with weeds. Rumor has it that the future park's retaining walls were made with the debris of "The Fortress," but it is only a rumor. The truth is there's nothing much left of the disaster that once gripped the nation and dramatically capped off decades of class warfare and labor struggle. There are just scattered pieces of remembrance, here and there.

Explosion in Ink Alley

"Take the granite which the age wrought for us, to build our TIMES Citadel, where we may fight for Truth, do mighty battle 'gainst the wrong." -- Eliza A. Otis 1

"One instant busy occupation, lights, the whirr of machinery, the next black midnight, smoke that overpowers, flames that shot their wicked tongues from basement to roof." -- Los Angeles Times, October 1, 19102

On July 1, 1887, the Los Angeles Times threw open the doors to its new six-story, $25,000 headquarters in the heart of L.A.'s bustling civic and governmental center. Visitors -- including many prominent citizens carefully recorded the next day in the Times -- streamed in all day, impressed with the building designed in a "chaste and massive modern," "European" style. The first granite building in Los Angeles (quarried from the mountains behind Monrovia), it boasted departments "connected by speaking tubes," a freight elevator, and a copy chute which ran between the business office and editorial rooms. The front counter was grandiosely "fashioned from wood from Union and Confederate ships, from California missions and Lincoln's death bed." 3 A 10-foot arched alley that would hold barrels of ink ran behind this "fortress." After 1891, a giant iron statue of an eagle, the symbol of The Times, kept watch above its grand turret.

That the building looked more like a fortified castle than a city newspaper was no mistake. For the Times was helmed by "General" Harrison Gray Otis, and he considered himself a warrior of the pen and the sword. He was a Civil War veteran, and he led troops in the Philippines during the Spanish American War. He also led the Times into a decades long battle with the American Union Movement, advocating "open-shop" businesses while relentlessly vilifying union leaders. By 1910, the union wars had reached a fever pitch across the country with countless strikes, tales of intimidation, and bombings of open-shop projects. Otis and his son-in-law and right-hand-man Harry Chandler were considered by union leaders to be the reason for unionism's stagnation in Los Angeles, and threats of retaliation had become a weekly occurrence.

The work of the Times' "troops" went on, undeterred. In the first hour of October 1, 1910, around 100 employees were in the venerable "old citadel." The morning edition had just gone to press and composers, engravers, and linotypers were busy at work setting the paper. A telegraph operator waited to hear the results of the Vanderbilt Auto Race from the East, and Harry Chandler's diligent young secretary, Wesley Reeves, worked at his desk. The handsome, well-connected night editor Churchill Harvey-Elder sat in his office, chatting with county editor Charles Lovelace and other associates. A little after 1:00 a.m., a few workers came up from the basement of the building, claiming to smell gas. At 1:07, a huge explosion originating in Ink Alley rocked the building.

"My god, they have got us at last!" Elder shouted at Lovelace. 4

The initial explosion was so strong it sent people on nearby sidewalks flying, and shattered glass in crowded taverns across the street. The whole first floor wall on Broadway was torn away and smoke filled the building. Within the time it took to run from the police station half a block away, three floors of the building were in flames. Angelenos poured into the streets and were met by a horrifying scene. According to the Times:

Flames and smoke filled the east stairway on First Street, driving down in a frenzied panic those employees of the composing room who had been so fortunate as to reach the landing in time. Elbowing past the last of these fugitives, men fought their way up to the first floor with flashlights and handkerchiefs over their faces. Their efforts were unavailing, the blistering hot ... flames almost upon them and licking down at them fiercely, drove the would be rescuers back hurriedly ... They could hear clearly the cries of distress, the groans and screams of the men and women who, mangled and crippled by flying debris from the explosion, lay imprisoned by flames, about to be cremated alive. Along the windows of the editorial and city rooms, on the south side of the building, through a choking volume of black smoke, could be seen men and women crowding about the windows on the third floor. The cries for ladders were frantic. A fire wagon drove up at full speed. Groans greeted it when it was seen that it was but a hose wagon instead of a hook and ladder truck. "Nets get the nets," was the yell. A policeman running up from headquarters was carrying a short ladder, pathetically inadequate. Someone called him a fool, but the ladder saved the life of [Charles] Lovelace, the county editor, who jumped upon it and escaped with a broken leg and some minor burns. Other fire apparatus thundered up. The nets were jerked out ... but by that time the fire had surged through the building with such rapidity that it was impossible to approach the reddening walls with them, and those unfortunates who had not jumped with Lovelace were doomed. In less than four minutes from the time the explosion was heard the entire building was ablaze. 5

But nothing could match the horror of those trapped inside the building. Men and women who had not been killed by the explosion scrambled in the heavy smoke, fighting to get to exits first. A solicitor remembered "going down the fire escape, a young man who was covered in oil fainted across my back, and I turned and grabbed his arm, but the flesh came off with the cloth of his shirt in my hand, and it sickened me, and I let go of him." 6 A foreman recounted that he started for the fire escape but in the rush of people for the elevator shaft he was born off his feet and fell into the shaft, dropping two stories atop newly deceased coworkers. He escaped by breaking through a glass and wood partition and found his way into the mail room, whence he escaped through the mail chute. Churchill-Elder, badly burned, jumped from the building, only to die at the hospital a few hours later.

Harry Chandler, who had only left work less than an hour before at his wife's insistence, rushed to the scene and attempted to help. Tears streaming down his face, he cried "my poor men," and more pointedly "the hounds!" 7 Just like the martyred Elder, he had no doubt what had caused the explosion to occur. He and Otis (en route from Mexico) had been planning for this day for a long time. As the building still burned, Chandler sent a cadre of bandaged, shell shocked employees to a secret auxiliary plant at the Los Angeles Herald. The Times would report on its own disaster.

In the morning light investigators gingerly began entering the smoldering ruins of "the Fortress" while thousands of Angelenos clogged surrounding streets. The body of Chandler's secretary, Reeves, was soon found, only a few feet from his desk. In another part of town the wife of Felix Zeehandelaar, the secretary of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association and an opponent of unions, was watering flowers outside her home when she found a ticking parcel. Shortly thereafter, a caretaker at General Otis' Westlake mansion "The Biouvac" found a suspicious suitcase, and quickly called the police. A policeman attempting to open the suitcase flung it just before it exploded in the Otis yard, causing a deep crater to form around it. These incidents seemed to confirm the headline the newsboys cried out on street corners, only a few hours later than usual, while hawking the four page emergency issue of the Los Angeles Times:

"UNIONIST BOMBS WRECK THE TIMES"

The Wrecking Crew

"I'm delegating you to run the dynamiters to the earth. No matter what the cost-and no matter who they are." -- Mayor Alexander to William J. Burns. 8

"You don't want me for safe blowing at all, but for that Los Angeles job." -- J.B. McNamara after being captured by detectives of the Burns agency 9

Word of the bombing quickly spread nationwide. Union activists and their supporters rushed to blame the explosion on a gas leak or sinister self-sabotage, while supporters of Otis and the Times stood behind the union theory. Debates raged in papers nation-wide. Many editorials echoed the punny sentiments of the Idaho Statesmen, when it stated: "when the building of the Times ... was blown up ... there was another explosion. It was in the public mind, and it blew off a lot of regard for organized labor." 10

Los Angeles was in mortal fear of more terror. General Otis arrived in town on the afternoon train, refusing the security offered him, and booming that he wouldn't give the murderers the satisfaction of seeing him with bodyguards. In the midst of the chaos, Mayor George Alexander summoned a small, stylish man with a heavy mustache to his office at City Hall. William J. Burns, America's "Sherlock Holmes" and future first director of the FBI, took the job on the spot.

The unexploded package at the Zeehandelaar home yielded the first clues -- an "infernal machine," that was comprised of 15 sticks of nitroglycerine attached to a cheap alarm clock. Markings on the sticks of dynamite soon led investigators to the Giant Powder Works Company near San Francisco. A company clerk's memories of the three men who had bought the dynamite would lead to a month-long, highly secretive investigation by Detective Burns and his associates. Over the next few months the investigation would lead Burns and his men "from San Francisco boatyards to an anarchist colony outside Seattle, to a hunters' camp in the snow-covered woods of Wisconsin, to a Chicago fortune teller and, finally, to the downtown streets of Indianapolis." 11

While Burns disappeared for weeks at a time, the Los Angeles Times soldiered on, conducting business from three temporary offices. A packed funeral for the victims was held at the Temple Auditorium, followed by the mass burial of shattered body parts at Hollywood Forever. Fundraisers were held and subscriptions were raised for their families. Rolls of paper at the site were still smoking 15 days after the blast. After the last human remains had been carried away in temporary wicker caskets, "trainloads of rubble" began taking debris from the ruins to dumps and iron works across the city. The Times described the scene thusly:

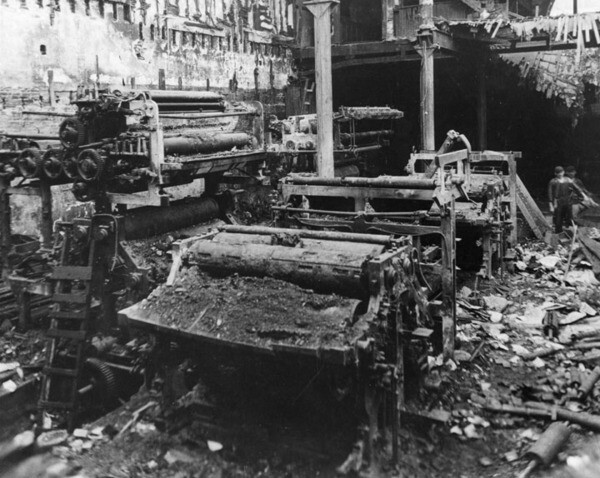

In the press room one of the giant presses, though badly rusted is almost intact. Its twin, ten feet away is merely torn and twisted junk ... The cover of the cashier's desk was burnt almost entirely off, but the interior is as fresh as if it had just come from the finisher ... Business houses adjoining were wholly or partially destroyed. The whole business section for blocks in every direction has directly felt the effects of the blow. 12

Debates about labor's involvement in the tragedy raged nationally as 1911 dawned. On April 23, 1911, papers across the country announced a bombshell. In the East, Detective Burns and his men had apprehended three men connected with the bombing of the Times. The three men -- brothers J.B. and J.J. McNamara, and Ortie McManigal -- were currently being held on a train that was speeding to Los Angeles. Detective Burns told rapt reporters:

I have been employed to locate and apprehend the men responsible for the dynamiting in Los Angeles. I have accomplished it beyond all doubt ... This country will be startled when the whole story becomes public. I have got a good start on this "crime of the century" and when the public is made familiar with all the terrible details people of this country and throughout the world will be startled. 13

Startling was an understatement. Burns had uncovered a multi-year, multi-state terrorist campaign, instigated by the highest-ups at the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers, an Indianapolis based union with a membership of around 12,000. Organized mostly by J.J. McNamara, secretary of the union, over 100 cross-country bombings of open shop businesses and projects had been carried out by "the wrecking crew," Ortie McManigal, J.B. McNamara and others. The brothers had planned the bombings of the Times and the Otis and Zeehandelaar homes, and J.B. had carried them out with the help of union cohorts in San Francisco. General Otis was vindicated. On the day the arrests were announced he declared resolutely:

It is time for the country and the law authorities to call a halt in the mad march of organized crime in the name of organized labor. 14

Reverberations

"I wanted the whole building to go to hell. I am sorry so many people were killed. I hoped to get General Otis." -- J.B. McNamara 15

"Murder is murder." -- Teddy Roosevelt on the bombing 16

J.B. McNamara was charged with the bombing of the Times. His brother, J.J., was charged with planning the bombing of an L.A. iron works. Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor, persuaded legendary lawyer Clarence Darrow to defend the brothers. Labor unions held rallies in honor of the McNamara's across the country. But right before the much anticipated trial was to begin in December, the brothers pled guilty. The powers that be in Los Angeles were relieved. According to one reporter present:

After the court proceeding there was a concerted dash for the District Attorney office. The office looked like a boarding school on the last Friday afternoon before vacation, deputies happy as schoolboys, they fairly danced from one room to another, and every minute or so there was a blinding flash of a newspaper photographer at work. 17

The brothers' admissions of guilt devastated the union cause in America for a generation. It was also pointed to as the reason Job Harriman, the socialist candidate for Mayor and one of the McNamara's attorneys, was crushed in the 1911 election. In his written confession, J.B. explained the details of the bombing:

On the night of September 30, 1910 at 5:45 p.m., I placed in Ink Alley, a portion of the Times building, a suitcase containing 16 sticks of 80 per cent dynamite, set to explode at 1 o'clock in the morning. I did not intend to take the life of anyone. I sincerely regret that these unfortunate men lost their lives, and if the giving of my life could bring them back, I would freely give it. 18

J.B was sentenced to life in San Quentin, and J.J. was sentenced to 15 years. Eventually, thirty-eight Iron Workers would be convicted of conspiracy, including the president of the union. Darrow was almost ruined, and would be tried twice for attempting to bribe potential jury members. He would be represented in these heavily covered trials by legendary Los Angeles lawyer Earl Rogers, who had himself witnessed the bombing firsthand. Darrow got off, but his reputation would be in tatters until the '20s when the trial of Leopold and Loeb, and the "Scopes Monkey Trial," cemented his reputation as a liberal hero.

The Times covered all these unbelievable twists and turns as they unfolded. On October 1, 1912, two years to the day of the bombing, the employees of the paper moved into their new home (which would house the paper until it moved to its current location across the street in 1934). Rebuilt on the very site "The Fortress" had once stood, the building was "wider, deeper, higher in the air, extended farther in the earth" than the old headquarters. It was also as "dynamite proof as humanly possible." A brass tablet commemorating the bombing victims was placed prominently at the entrance. And on the roof again perched the iron eagle, saved from the wreckage, "there to stand in his tarnished yet honored habiliments for uncounted years to come." 19

Additional Photos By: Hadley Meares

_____

1 "The Times" Los Angeles Times, Jan 1, 1887

2 "Unionist Bombs Wreck the Times" Los Angeles Times, Oct 1, 1910

3 "The Times" Los Angeles Times, Jan 1, 1887

4 Lew Irwin, "Deadly Times" pg. 103

5 "Unionist Bombs Wreck the Times" Los Angeles Times, Oct 1, 1910

6 Lew Irwin, "Deadly Times" pg. 104

7 "Unionist Bombs Wreck the Times" Los Angeles Times, Oct 1, 1910

8 Lew Irwin, "Deadly Times" pg. 143

9 "Grease stains in a suitcase" Los Angeles Times, April 25, 1911

10 "Strong words from the press on the unionite outrages" Los Angeles Times, Oct 11, 1910

11 "A blast that echoed through the century" Los Angeles Times, Oct 1, 2008

12 "times building in fragment, hauled off by the train" Los Angeles Times, Oct 23, 1910

13 "Finds stock of dynamite on property of McCanigal" Los Angeles Times, April 24, 1911

14 "Wires the facts to the world" Los Angeles Times, April 23, 1911

15 "Traces of conspiracy" Los Angeles Times, Nov 15, 1912

16 Lew Irwin, "Deadly Times" pg. 330

17 "Perpetrators of the crime of the century forced to confess" Los Angeles Times, Dec 2, 1911

18 "Terms in San Quentin for two McNamaras" Los Angeles Times, Dec 6, 1911

19 "Restoration day" Los Angeles Times, Oct 1, 1912