Counter Cliché: The Asian and Latino Bi-Cultural Experience

California hosts both the largest Hispanic and Asian population of any state -- and it's growing even faster. As the state's demographic continues to be in flux, so does its character ebb and flow. The Land of Sunshine is one that resists the matter-of-factness of census tick boxes. Instead, its artists investigate the gray areas that exist in between, and in the process, they surprise audiences into recognizing the multiple streams of heritage they ford themselves.

Inspired by the Mandarin flashcards her parents used to give her so she could learn Chinese, artist Audrey Chan created "Chinatown Abecedario," for the recent (de)Constructing Chinatown exhibition at the Chinese American Museum. In the video, Chan turned wordsmith and used alliteration to great effect, teaching her audience the ABCs of multicultural Los Angeles's Chinatown.

"The punk plucked pipa under the pagoda," states one frame, as a flickering image of a spiky-haired musician held the instrument aloft while seated on a classic Asian ceramic stool. "Tourists toasted with tea and Tecate," it says in another, as a teacup clinks glass with the spicy condiment.

After cycling through all 26 letters of the alphabet, the video goes on to translate the vignettes in Cantonese, Spanish, and Mandarin, touching on neighborhood issues and day-to-day realities along the way.

"I love learning languages and I've used programs like Rosetta Stone," says Chan, who drew each frame thrice and animated it, "I was fascinated by the sentences they use in language tapes. They are always so neutral. It's almost like they try to use the most innocuous sample sentences. My goal in this project was to make each sentence as culturally loaded as possible."

In that, she succeeds. By using a familiar rubric, Chan midwifes her audience into the world where Chinatown isn't just full of dimsum restos and Oriental tchotchkes. It is a neighborhood where disparate swaths of cultural fabric meet, then get stitched together at the seams to form a strange, but cohesive whole.

Chan's approach is playful yet provocative, without the usual rancour at the mention of race. Just as it should be. How could a real conversation occur if voices are constantly raised over the other?

"Art about identity is often self-segregated," comments Chan, "Even in the contemporary art world, black artists make art about being black. Asian artists make art about being Asian, and so on. It's almost like people are afraid they'll get in trouble when they cross the color line."

Artist Clement Hanami has no such worries. The Japanese artist once called East Los Angeles home. "It was fun. I grew up with mostly Latinos, playing and doing things regular kids do," says Hanami, "I'd go to their house, have a snack like tortillas with butter. Then I'd go home and have rice and hotdogs or something. I understood that we were in a community that had other cultures thriving and existing together."

For Hanami, multicultural wasn't a word, it was an everyday reality, and one that could be molded to fit his creative impulses. Perhaps the best pieces that capture this (ahem) free-wheeling spirit are his lowrider rickshaws. As its name suggests, the handmade transport is an amalgam of the Chinese manpowered vehicle and the tricked-out cars first improvised by Mexican-Americans in California. Hanami created the piece in response to his Latino friends giving him the moniker "Chino," despite his being Japanese.

"Identity is something that's inside of you. You really don't examine it in full, it's ingrained into you," says Hanami, who didn't take offense at the misnomer. He applies the same logic to his lowrider rickshaws. Instead of taking pre-existing rickshaws, Hanami fabricates each piece from the ground up, right up to the fluffy ball fringe that lines the vehicle's ceiling.

Over time, his more functional lowrider rickshaws have become even more brazen. His latest iterations include hydraulics that lift the transport up and down, much like its motorized counterparts. His pieces have been spotted rolling around San Jose down to Mexico.

Others might fear the backlash of addressing race, but Hanami's lowrider rickshaws diffuse that impulse. "They're meant to be humorous in that we can look at our culture and identities and understand that there are similarities in how we look at each other."

Identity, however, isn't something to be taken lightly, especially when it's used to pigeonhole. Born to parents of Japanese and Mexican descent, Shizu Saldamando knows her ethnicity is a novelty, but rankles at the thought that this accident of birth has somehow confined her work strictly along those lines.

"What's really problematic for me is that white artists aren't given the same sort of 'luxury,'" says Saldamando, whose works have already graced the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery. "Whiteness is sort of taken for granted as a normalizing factor. Everything else is other-ized as being different."

An incessant portraitist since middle school, Saldamando first latched onto her art as a way to pay homage to those like her. "I was always felt that there was a lack of relatable imagery for me especially in terms of watching TV, media, popular culture. There weren't people I could relate to," says the artist, "Portraiture was a way to document my friends. It was born out of love for them and all of their fucked-up-ness."

Her subjects aren't the cookie-cutter characters we see in primetime television, but real, breathing beings actively building their identity. Saldamando's work reflects her fascination with self-creation.

"I'm just inspired by people that are really into something, that can create their own subculture or are artists in their own right by the way they style themselves," says the artist.

Using a cheap point-and-click camera, Saldamando attends concerts, art openings, and social events with friends and takes photographs all night. She then chooses one photograph, strips it of its context, and renders her subject in supreme accuracy, down the faint skull and crossbones detail that covers her subject's bag. The obvious care she takes with her work leads viewers to wonder about her subjects and the lives they lead.

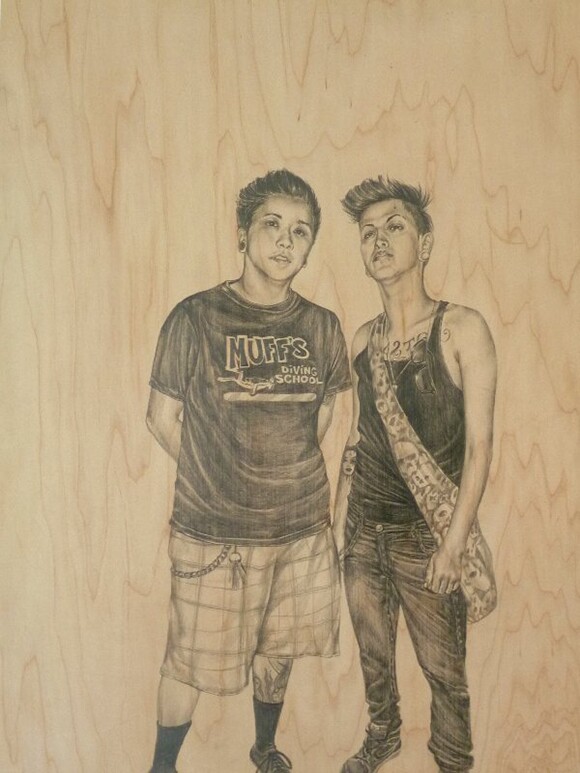

Take "Cristina Y Felix." Using wood panel for background, she takes graphite and brings to life her gender bending friends. "They're gender androgynous in way they both construct themselves," says Saldamando.

"Felix -- on the right -- has insanely flexed eyebrows. He wears a lot of make-up. He's a beautiful guy. Cristina is more butch and doesn't wear any make-up," says the artist, "Seeing them together in a concert, hanging out, personalizing their style, that's something I wanted to honor. I don't think they'd be cast in any NBC dramas anytime soon."

Saldamando's work is heavily influenced by Chicano art sensibilities and her Japanese heritage, but much like her subjects, she re-configures those strains, adding to it the warmth of craft culture with the edge of the punk rock music scene to produce work that's unmistakably hers. "I'm trying to create this anti-binary way of looking at things," says the artist, "They're just normal people and they're relatable."

As California continues to welcome an influx of cultures, its residents will more likely come face to face with the different, odd and exotic, but these artists' works remind us that no matter how divergent, there will always be unexplored common ground to be found.